-

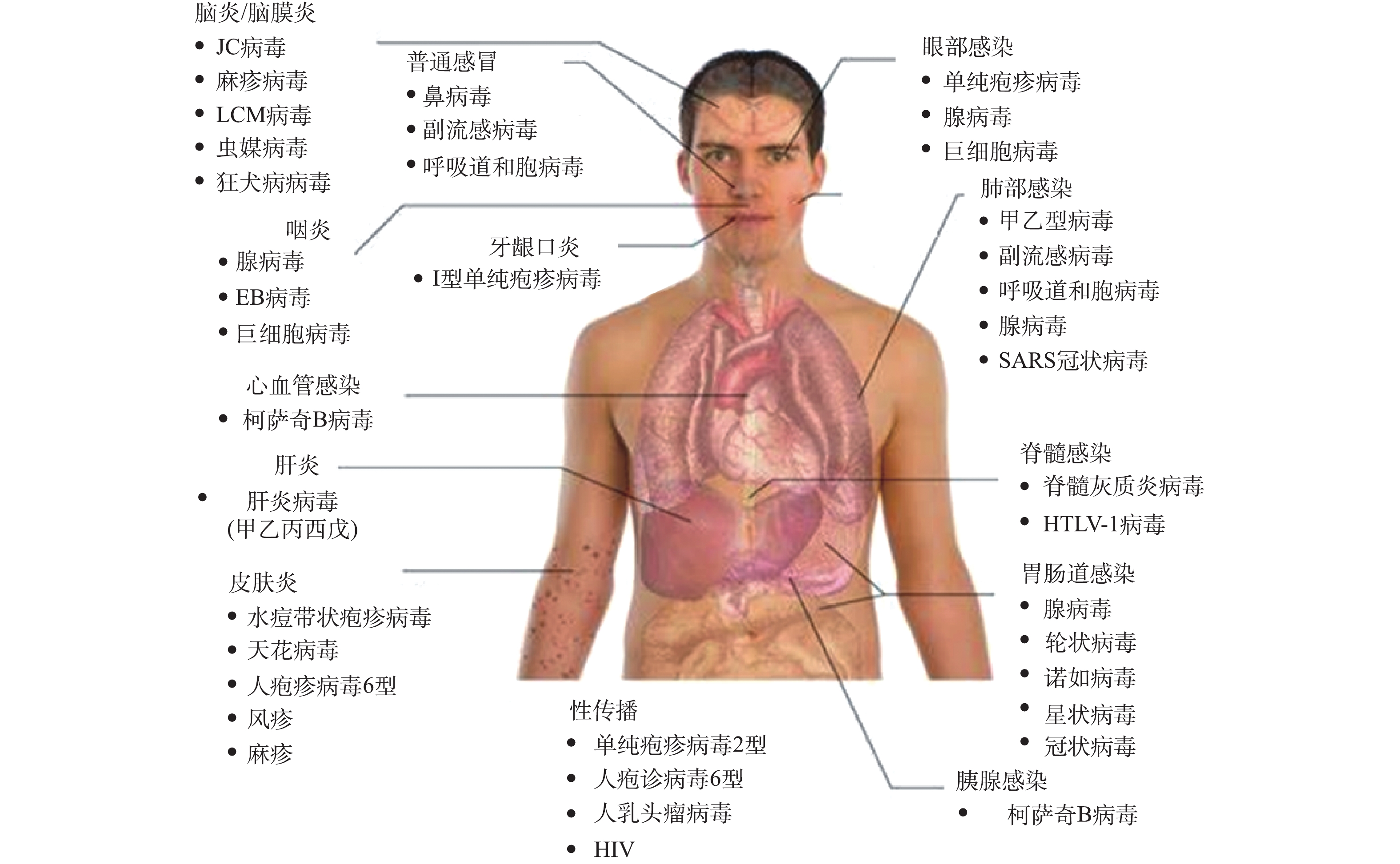

病毒是一类由遗传物质(脱氧核糖核酸(DNA)或核糖核酸(RNA))和蛋白质组成的生物大分子,其利用宿主细胞内的代谢系统来进行自身繁殖。病毒种类繁多,国际病毒分类委员会(International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses,ICTV)认定的病毒分类系统中以目、科、属、种为分类单元,目前已发现并鉴定的病毒有近5 000种。医学上按照临床症状将病毒分为肺部感染病毒、胃肠道感染病毒(包括腺病毒、轮状病毒、冠状病毒、星状病毒、诺如病毒等)、肝炎病毒、皮肤感染病毒和肿瘤病毒等(见图1)。值得注意的是,肺部感染病毒(通过呼吸飞沫、气溶胶传播)、胃肠道感染病毒(通过食物、饮水传播)2种分类中均含有冠状病毒,说明冠状病毒存在通过饮用水及其形成的气溶胶为介质感染人体的风险[1]。

2019年末,在我国湖北省武汉市暴发的COVID-19新型冠状病毒疫情为我国公共卫生安全敲响了警钟。新冠病毒的暴发与流行严重威胁我国乃至全球居民身体的健康[2]。及时、有效地阻断病毒的传播途径是控制疫情蔓延的关键环节。虽然尚无实验结果直接证实病毒可通过粪-口传播,但由于在确诊患者粪便中多次检测到病毒核酸物质[3],表明除已明确的飞沫传播方式外,很可能存在水体传播的潜在风险,需引起环保监管部门、给排水行业、科研人员与公众的足够重视。

在1947年,美国已从排入纽约市河流的污水中检测出脊髓灰质炎病毒,并认为与当时纽约脊髓灰质炎的流行病相关[4]。随着病毒检测方法的发展,饮用水中病毒污染以及由其导致的传染病的流行逐渐进入公众视野。饮用水的消毒是20世纪公共卫生领域的创举之一,是饮用水微生物安全风险控制的必要措施。常见的饮用水消毒技术包括投加化学消毒剂(如氯、氯胺、二氧化氯和臭氧等)、物理紫外线辐射等[5]。美国环保署(USEPA)的《国家饮用水水质标准》规定,饮用水中病毒检出应为零;在实际的水处理中则参考世界卫生组织(WHO)绩效目标的限值方式,要求饮用水处理工艺对肠道病毒灭活率达到4个对数单位(即99.99%)[6]。20世纪饮用水消毒工艺的应用有效控制了水中致病微生物对人体的健康风险。

全文HTML

-

经口摄入是病毒感染人类的主要途径之一。水环境中病毒的存在增加了病毒经饮用水传播的风险。由于病毒在水中可存活时间较长(> 1个月),感染剂量低,且对饮用水消毒剂的抗性高于细菌,因此,饮用水病毒安全性不容忽视[7]。水介质中常见病毒种类及特性[8-10]如表1所示,其中肠道病毒包括脊髓灰质炎病毒、柯萨奇病毒和埃可病毒等。不同种病毒的核酸、尺寸和形态各异,潜伏期短则1 d,长则可至数月,入侵人体后可引发肠胃病、发热和呼吸系统感染等多种疾病,危害人体健康。

目前,我国现行的《生活饮用水卫生标准》(GB 5749-2006)已将总大肠菌群、耐热大肠菌群、大肠埃希氏菌和菌落总数4项细菌指标和隐孢子虫、贾第鞭毛虫2项原生动物指标列为饮用水中的微生物指标,但尚未将病毒指标纳入标准。世界范围内也仅有美国、加拿大等少数国家对饮用水中的病毒规定了限制标准。为评估水环境的病毒安全性,许多研究采用典型病毒(如肠道病毒、腺病毒等)作为模式病毒,如我国的《消毒技术规范(2002年版)》采用脊髓灰质炎病毒(属肠道病毒)I型疫苗株来评价消毒剂对病毒的灭活能力。细菌病毒(噬菌体)也被用作模式病毒,代表菌株有MS2噬菌体、f2噬菌体和ΦX174噬菌体等,其具有与肠道病毒相似的形态、结构、生物学特性和对消毒剂的抗性,并且容易定量测定。消毒剂对病毒的灭活效果可通过病毒或噬菌体的灭活对数值来量化。饮用水消毒的CT (concentration time)值,是饮用水消毒对病毒灭活效率的重要指标。USEPA的地表水处理指导手册提供了不同消毒剂在一定条件下对肠道病毒灭活的CT值[11],然而受温度、水质(pH、有机物、无机离子等背景基质)、消毒装置布设、消毒剂投加方式等因素影响,不同饮用水消毒技术对病毒的灭活效果尚缺乏系统的对比与评估。

-

游离氯(即由氯气水解形成的HOCl和OCl–)是当前广泛使用的消毒剂。USEPA污染物候选名单(contaminant candidate list,CCL)中包括人类腺病毒2型、埃可病毒1型、柯萨奇病毒B5型和小鼠诺如病毒(作为人类诺如病毒的替代指标)等典型病毒。有研究[12]比较了游离氯对这4种病毒的灭活效果,发现在未经处理的地下水和经部分处理的地表水中,氯消毒均对小鼠诺如病毒最有效,CT值为0.034 mg∙min∙L–1,灭活率可达3个对数单位(水温为5 ℃,pH为7~8),其次是人类腺病毒2型和埃可病毒1型,而对柯萨奇病毒B5型消毒效果最弱,所需CT值为2.3~7.9 mg∙min∙L–1。研究[13]也发现了小鼠诺如病毒以及腺病毒对游离氯高度敏感,游离氯对腺病毒2型病毒实现3个对数单位灭活的CT值为0.023~0.027 mg∙min∙L–1(pH为 7,温度为4 ℃)[14]。游离氯对病毒的灭活具有广谱、无选择性特征,在一定的CT条件下可有效灭活多种病毒。

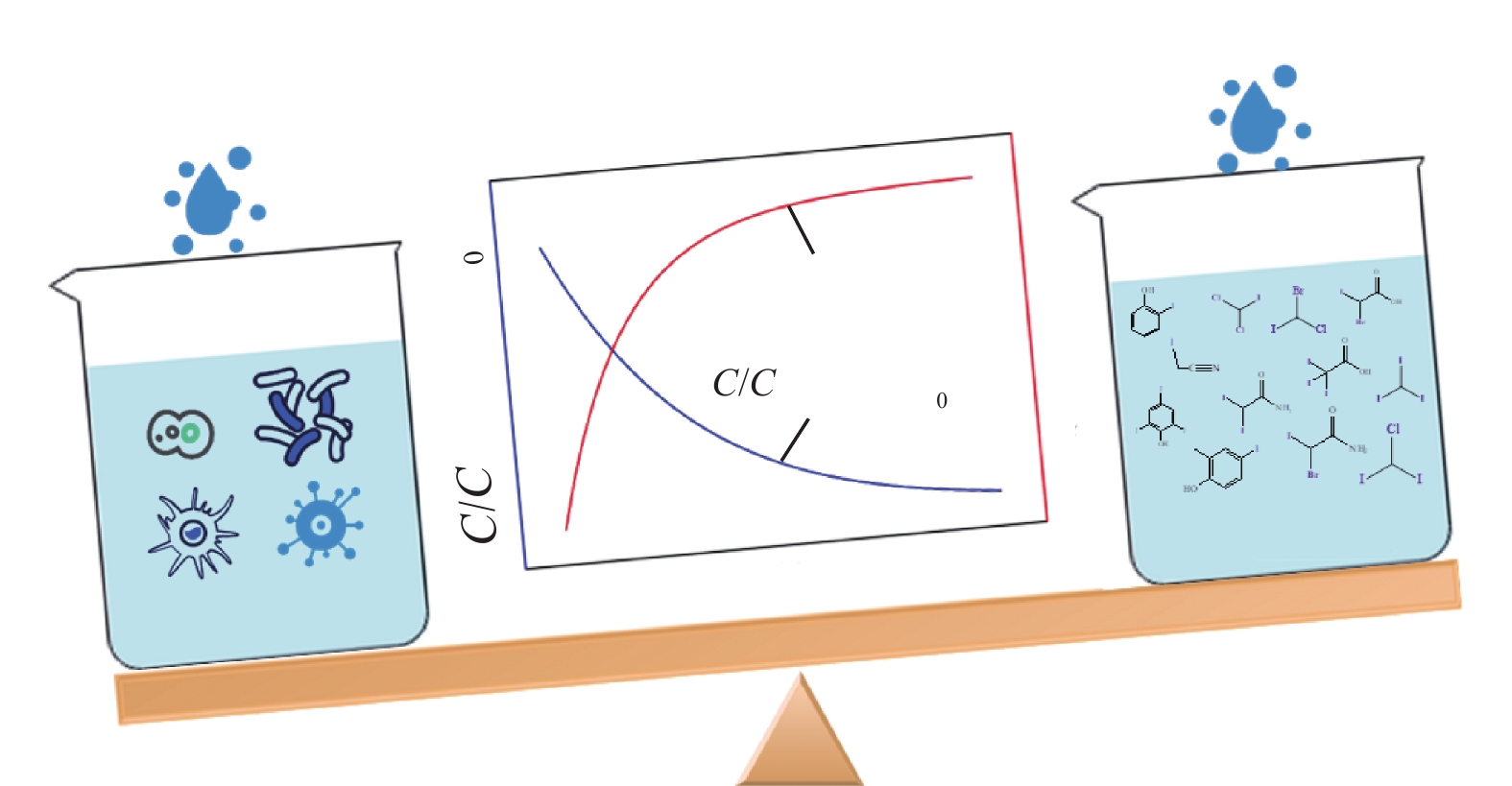

饮用水背景水质会显著影响游离氯的灭活效果,pH过高,会降低氯对病毒灭活的有效性。当pH > 8时,游离氯在水中形态以OCl−为主,其消毒效果弱于HOCl。游离氯对病毒的灭活能力通常随温度的升高而增强,当温度从5 ℃增加到25 ℃时,氯对脊髓灰质炎病毒的灭活效果可提升2倍[15]。此外,在饮用水输配系统中,维持一定的残余氯量是保证管网中微生物水质指标安全的必要条件。已有研究[16]报道,管网中无氯时供水节点诺如病毒感染风险显著提升(见图2)。我国饮用水消毒中规定出厂水余氯量不小于0.3 mg∙L–1,接触时间不小于30 min,可有效灭活水中绝大多数病毒。值得注意的是,游离氯消毒过程中存在生成三卤甲烷、卤乙酸等有害消毒副产物的风险(见图3),且游离氯的有效性很大程度上取决于背景水质的有机物、氨氮含量。为控制消毒副产物的生成,游离氯消毒时应严格控制氯的投加量;为提升游离氯对病毒的灭活效果,强化饮用水常规、深度处理工艺对背景有机物、氨氮的去除至关重要。

-

氯胺(以一氯胺为主)由氯和氨反应生成。由于氯胺的氧化能力较弱,氯胺需要更长的接触时间才能达到与游离氯相同级别的对病原体的灭活作用,再加上氯胺比游离氯更稳定,在饮用水处理中常被用作二次消毒剂,来维持管网中的残余消毒剂,减少消毒副产物的生成,控制生物膜的增长。CROMEANS等[13]研究了一氯胺溶液在5 ℃、pH=8条件下对多种病毒的灭活效果,发现其对埃可病毒1型最有效,达到3个对数单位灭活率的CT值为18 mg∙min∙L–1,其次是诺如病毒(CT值为78 mg∙min∙L–1)和柯萨奇病毒B3型(CT值为330 mg∙min∙L–1)。相比而言,一氯胺对这些病毒的灭活能力远低于游离氯[17],一氯胺灭活4个对数单位埃可病毒和人类腺病毒的所需CT值均高于1 000 mg∙min∙L–1。腺病毒易被游离氯灭活,但它对一氯胺的灭活有很强的抗性[18],灭活效率受一氯胺浓度及氨氮/氯的物质的量之比影响较小,随着pH的增大和温度的降低而下降[19]。此外,水体颗粒物、离子强度等水质条件也影响一氯胺的消毒效果[20]。

-

二氧化氯(ClO2)是一种易溶于水的氧化剂,可氧化水中铁锰离子,降低水的色度,且不与氨或有机物反应生成消毒副产物。然而,ClO2化学稳定性低,通常需现场制备。ClO2对耐一氯胺和紫外灭活的腺病毒具有高效的灭活效果,0.47 mg∙L–1的ClO2消毒0.25 min即可实现腺病毒40型灭活效果> 4.2个对数单位(pH为 8,温度为15 ℃)[21]。LI等[22]报道了甲型肝炎病毒暴露于7.5 mg∙L–1的ClO2 10 min后,感染性完全丧失,抗原结构经ClO2消毒10 min后被完全破坏。对于轮状病毒的灭活,投加0.1 mg∙L–1的ClO2 60 min后可达到4个对数单位的灭活效果(pH为7.2,温度为20 ℃),说明ClO2的消毒效率优于游离氯消毒。根据模型得到ClO2和氯消毒的相应CT值,分别为1.21~2.47 mg∙min∙L–1和5.55~5.59 mg∙min∙L–1[23]。

水中pH对ClO2灭活病毒有重要影响。pH为10时ClO2对脊髓灰质炎病毒的灭活效率[24]比pH为6时的效率更高。类似的结果在ClO2灭活轮状病毒时也出现了,即随着pH增加,病毒灭活率提高[25]。有趣的是,这一结果与氯在不同pH时灭活肠道病毒的效果相反。分析其原因,一方面高pH增加了病毒对ClO2攻击的敏感性,另一方面也可能是因为ClO2在碱性溶液中的形态(

${\rm{ClO}}_3^ - $ )是灭活病毒的主要活性物种。 -

臭氧(O3)是一种强广谱氧化剂,对细菌、真菌及其孢子、病毒和原生动物都具有灭活活性。除了自身具有强氧化性(氧化还原电位为2.07 mV)这一特点以外,在碱性条件下,O3易生成羟基自由基(·OH)和超氧自由基(

${{\rm{O}}_2}{ \cdot ^ - }$ )等自由基,这些自由基也可破坏病毒结构[26]。研究还发现,O3灭活水中多种病毒的有效性顺序为:Qβ 噬菌体> 埃可病毒 ≈ MS2噬菌体 > Φ174噬菌体 ≈ T4噬菌体 > 腺病毒 > 柯萨奇病毒B5型[27]。柯萨奇病毒对O3的抗性最高,灭活率为2个对数单位所需的CT值为8×10–3 mg∙min∙L–1,明显高于其他肠道病毒(如埃可病毒,CT值1.9×10−3 mg∙min∙L–1)。MS2噬菌体在O3消毒中失活速率常数受温度影响较小,pH为6.5时,温度上升10 °C,其失活速率常数仅增大了1.2倍。O3对脊髓灰质炎病毒1型也有较好的灭活效果,0.37 mg∙L–1的臭氧在5 °C的pH为7的缓冲溶液中作用10 s,即可对脊髓灰质炎病毒1型的灭活率达到3个对数单位[28]。O3的稳定性易受pH和温度等因素的影响。随着pH的增加,O3水溶液的稳定性降低,造成了O3对轮状病毒的消毒效率在碱性pH下降低[29]。随着温度的升高,O3在水中溶解度降低且分解速率加快,但O3与反应物的作用速率增加。因此,在使用O3灭活水中病毒时,应考虑背景水质、温度等的影响。通常O3比游离氯对病毒的灭活效率更高,但需注意的是,O3在水中衰减迅速,且无持续的消毒效力。目前,O3-生物活性炭(biological activited carbon,BAC)工艺在我国大中型饮用水厂深度处理工艺中广泛应用(见图4),其O3投加量、接触时间控制在0.5~3.0 mg∙L–1、10 min左右。深度处理工艺在去除微污染物、消毒副产物前驱物的同时,对水中的病毒也有较好的灭活效果,但当前深度处理工艺对病毒迁移去除的研究较少,还有待进一步开展。 -

紫外线(ultraviolet,UV)消毒具有不添加化学试剂、无腐蚀性、操作方便、不产生消毒副产物等优点,是一种绿色、高效的消毒工艺。紫外线的UVC波段(波长200~280 nm)可通过辐射改变病毒染色体与衣壳灭活病毒。埃可病毒1型和11型、柯萨奇病毒B3型和B5型、脊髓灰质炎病毒1型被去除3个对数单位时所需的UV剂量分别为25、20.5、24.5、27和23 mJ∙cm–2[30]。甲肝肝炎病毒暴露于20 mJ∙cm–2的UV剂量时,其灭活率可达到3个对数单位[31]。UV可灭活浓缩血小板中的埃博拉病毒和中东呼吸综合征冠状病毒,150 mJ∙cm–2 UV剂量下,灭活率分别超过4.5个对数单位和3.7个对数单位[32]。UV消毒对MS2、Φ174、Qβ和T7等噬菌体也具有良好的灭活能力[33]。有研究[34]发现,病毒结构会影响UV消毒效率,与单链病毒相比,双链病毒对UV灭活的抗性更强,可能是由于当双链病毒在UV光照时只有一条链受到损伤,剩余未受损的链可作为宿主细胞酶修复的模板。值得注意的是,腺病毒对UV照射有较强的抵抗力,需3倍饮用水UV国标剂量(120 mJ∙cm–2)才能达到3个对数单位灭活率,要达到4个对数单位灭活率UV剂量应≥200 mJ∙cm–2[35]。在常用的饮用水UV消毒剂量下(40 mJ∙cm–2),除腺病毒外,绝大多数病毒均可达到4个对数单位的去除率。

消毒剂的灭活机制决定了各消毒剂的灭活作用位点与影响因素,但对于各消毒剂灭活机制的认识还非常有限。已有研究[27]考察了游离氯、ClO2、UV等消毒工艺灭活MS2噬菌体的机理,发现各种工艺对MS2噬菌体灭活机理各不相同。部分消毒剂灭活病毒的机制依赖于对特定病毒组分的修饰,导致不同病毒对灭活工艺的敏感性也大不相同。对于没有基因组修复机制的病毒(如单链RNA病毒),UV是较为有效的灭活方法。这是由于蛋白和基因组的修饰都会导致病毒感染性的降低,但可修复病毒少量的突变可以抵制UV的灭活效果,因此,病毒更容易朝着耐UV灭活的方向进化[36]。游离氯灭活病毒是一种非特异性的反应过程,可导致高水平的非特异性基因组和蛋白损伤,但须指出的是,并不是所有的基因组和蛋白损伤都会使病毒失去活性[35]。

2.1. 游离氯消毒

2.2. 氯胺消毒

2.3. 二氧化氯消毒

2.4. 臭氧消毒

2.5. 紫外线消毒

-

前文中叙述的消毒技术均可在一定程度上灭活饮用水中的病毒,但各自又有一定的适用范围与局限性,且消毒工艺前的进水水质(浊度、背景有机物和吸光度等)需达到一定的标准才能保证消毒的效果。因此,须先确定饮用水原水中高频检出的可感染病毒,再依据背景水质、处理工艺、目标病毒的特征来合理配置消毒工艺进行病毒的灭活。在保证水质微生物指标安全的同时,有效控制水中消毒副产物的生成,将成为未来水消毒工艺发展的主要方向。

-

因为饮用水中存在的有机、无机化合物在化学消毒过程中会不可避免地与消毒剂发生化学反应,所以饮用水水质的净化过程(水源地保护、常规处理和深度处理)对消毒工艺效能影响较大。此外,水中存在的有机物和悬浮固体可为吸附在这些颗粒上的病毒提供载体与保护。快速沉淀、过滤去除水中的悬浮固体亦可去除部分病毒。已有研究[37]表明,冠状病毒在未过滤出水的存活时间比滤后水中的存活时间长,表明悬浮固体可为水中的冠状病毒提供存活的“温床”。背景水质中成分复杂的有机物还会使包膜状的冠状病毒失活检测失灵,冠状病毒包膜的疏水性很可能使得冠状病毒在水中的溶解性降低,增加冠状病毒粘附在水中悬浮固体上的可能性。因此,保持消毒工艺中饮用水水质(有机物、氨氮和浊度等)稳定、达标是保证消毒效率、降低饮用水微生物安全风险的有效措施之一[38]。

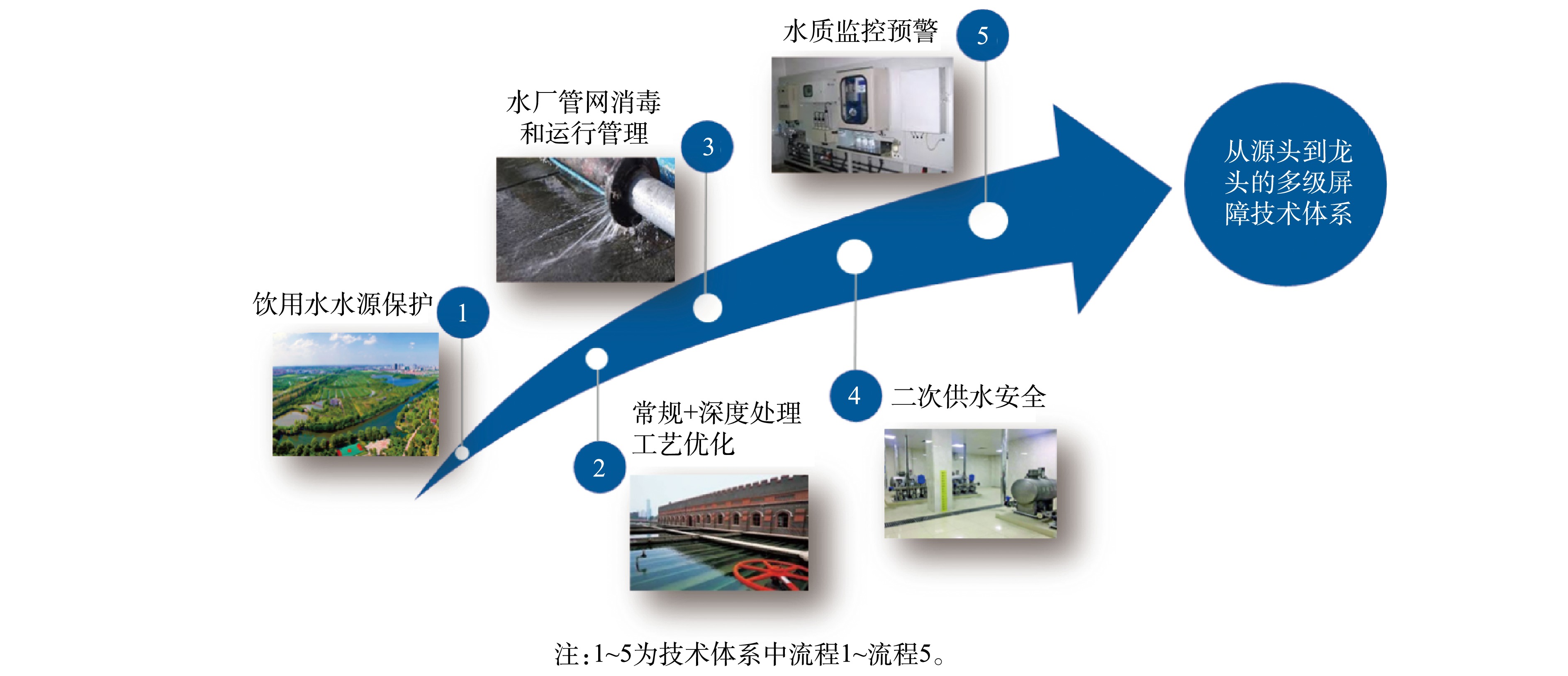

自《中国国民经济和社会发展第十一个五年规划纲要》实施以来,我国饮用水行业沿着饮用水水源保护、水厂常规处理和深度处理工艺优化、水厂管网消毒和运行、二次供水以及水质监控预警等多方向,逐步构筑了饮用水从源头到龙头的多级屏障技术体系(见图5)。饮用水水源保护立足于“源头”水质的保护,按照流域和区域进行水资源规划、优化水源配置,合理布局饮用水水源,优先保障充足优质饮用水水源;水厂常规处理和深度处理工艺优化运行确保我国饮用水常规水质指标达到标准要求、新兴污染物浓度实现有效控制;水厂管网消毒和运行、二次供水以及水质监控预警等确保饮用水在消毒、输配、二次供水过程中水质的生物、化学稳定性,为“龙头水”达标实现全流程技术与监测保障。

饮用水多级屏障技术体系的建立确保了我国饮用水水质全面、稳定达到国家《生活饮用水卫生标准》(GB 5749-2006)的要求。尽管我国当前执行的水质标准未规定病毒的限值,但对浊度、微生物等指标有明确的限定。普遍采用的常规处理工艺、深度处理工艺(O3-BAC、超滤工艺)、消毒工艺对病毒均有一定的去除效果。在保证饮用水水质稳定达标、足够的消毒剂浓度和接触时间前提下,考虑到病毒污染的类似性,亦能保证饮用水处理工艺对病毒的去除效果。冠状病毒属包膜病毒,通常比非包膜肠道病毒对温度更敏感、在水环境中更易失活。冠状病毒在污水中停留2~3 d后可减少3个对数单位[39]。在环境温度下,冠状病毒与其他肠道病毒相比会更快失活,因此,冠状病毒在水中的传播应弱于肠道病毒。我国居民多饮用煮沸水,由于冠状病毒对温度敏感性较高,饮用水煮沸可成为阻断新型冠状病毒通过饮用水传播的另一重要屏障。

3.1. 现有消毒工艺的局限性

3.2. 基于饮用水多级屏障处理工艺的饮用水微生物安全风险控制

-

病毒在全球水环境中普遍存在,人类面临病毒暴露、感染的风险。然而对病毒在水环境、水处理工艺中的相关认识仍有待深入,亟待建立高灵敏度、特异性的多种病毒浓缩、分析方法,以准确评估其在水环境、水处理工艺中的存活、迁移与去除规律,并开发高效的饮用水消毒工艺。通过构建从源头到龙头的饮用水多级屏障技术,能有效控制由病毒引发的饮用水水质风险。

下载:

下载: