-

饮用水安全是一个很严重的全球性问题,关系到人类的健康。随着水污染的严重和人类的增加,大量的污染物在水源中被检测出[1-2]。传统的水处理工艺(混凝、沉淀和过滤)对微污染物的去除不是很有效,除非添加其他处理工艺[3-5]。预氧化工艺能够有效去除微污染物,在饮用水处理厂中被广泛采用[6-7]。

在水处理过程中,常用的预氧化剂有高锰酸钾(KMnO4)和过氧化氢(H2O2)[8-10]。由于KMnO4和H2O2具有各种缺点,限制了它们在饮用水处理过程中的使用。例如,KMnO4能够引起浊度和颜色的增加[11-12]。由于需要严格的酸性条件、自由基的产率及利用率低以及H2O2不够稳定等原因,所以限制了芬顿氧化的使用[13-14]。相比KMnO4和H2O2,单过硫酸盐(PMS)具有无色、稳定、溶解性高等特性[15-16],因此,PMS也能够被应用在预氧化过程中。

氯离子(Cl−)是天然水体中广泛存在的卤素离子[17]。PMS不仅能够氧化降解有机物,同时也能氧化Cl−为有效氯(HOCl/OCl−)[18]。HOCl/OCl−会和有机物发生化学反应生成消毒副产物(DBPs)[19-20]。DBPs具有致畸、致癌和致突变的特性[21-23]。长期饮用含有DBPs的饮用水,会使癌症的患病概率显著上升。如何减少PMS预氧化体系中DBPs的生成值得研究。

氨基酸(AAs)广泛的存在于天然水体中,在天然水体中的浓度约为50—1000 µg·L−1,占总溶解性有机氮和溶解性有机碳的比例约为35%和2.6%,同时也是DBPs的重要前体物[24-25]。酪氨酸(Tyr)作为一种天然AA,广泛存在于多肽、蛋白质和藻类中[26]。此外,PMS已经成功的应用在部分小水厂和泳池的消毒过程中。因此,Tyr被选定为DBPs的前体物,研究PMS预氧化体系中DBPs的生成特性。

本论文以Tyr和实际水样为研究对象,研究PMS预氧化体系中,预氧化时间、PMS浓度、Cl−浓度、pH对DBPs生成以及毒性的影响,为DBPs的合理控制提供理论依据。

-

三氯甲烷(TCM)、水合三氯乙醛(TCAL)、二氯乙腈(DCAN)、三氯乙腈(TCAN)、二氯乙酰胺(DCAM)和三氯乙酰胺(TCAM)的标准样品购自CanSyn公司(多伦多,加拿大)。氯化钠、PMS(KHSO5·0.5KHSO4·0.5K2SO4,≥ 42% KHSO5)、Tyr等所有试验用到的化学药剂均购自阿拉丁试剂有限公司(上海,中国)。实际水样取自某饮用水水源地,超纯水由Millipore Milli-Q Gradient水净化系统(比勒利卡,美国)制备。

-

预氧化试验:研究预氧化时间[t = 0.5、1、1.5、2、2.5 h,DOC(Tyr溶液)= 5.4 mg·L−1,DOC(实际水样)= 2.5 mg·L−1,PMS = 200 µmol·L−1,Cl−(Tyr溶液)= 1 mmol·L−1,Cl−(实际水样)= 2.9 mmol·L−1,pH = 7]、PMS浓度[PMS = 100、200、400、600、800 µmol·L−1,DOC(Tyr溶液)= 5.4 mg·L−1,DOC(实际水样)= 2.5 mg·L−1,t = 2 h,Cl−(Tyr溶液)= 1 mmol·L−1,Cl−(实际水样)= 2.9 mmol·L−1,pH = 7]、Cl−浓度[Cl−(Tyr溶液)= 0.5、1、1.5、2、2.5 mmol·L−1,DOC(Tyr溶液)= 5.4 mg·L−1,t = 2 h,PMS = 200 µmol·L−1,pH = 7]和pH [pH = 5、6、7、8、9,DOC(Tyr溶液)= 5.4 mg·L−1,DOC(实际水样)= 2.5 mg·L−1,t = 2 h,PMS = 200 µmol·L−1,Cl−(Tyr溶液)= 1 mmol·L−1,Cl−(实际水样)= 2.9 mmol·L−1]对DBPs生成的影响,反应温度为25 ℃。所有实验样品均做平行样,误差棒代表3组数据的标准偏差,相对标准偏差低于20%。

-

预氧化试验结束后,添加抗坏血酸(浓度为余氯的2倍)终止反应[24]。取10 mL反应液并用0.22 μm滤膜过滤,然后注入到25 mL的透明玻璃瓶中并加入2 mL甲基叔丁基醚进行液液萃取,将上层液体转移至气相色谱分析专用的进样瓶中进行检测。

DBPs使用气相色谱(GC/ECD,Agilent 7890A)检测,色谱柱为HP-5毛细管柱(30 m×0.32 mm×0.25 µm)。GC/ECD运行参数:载气为氮气,载气控制方式采用压力控制,压力为8.4 psi,总流量为20 mL·min−1,柱流量为2 mL·min−1。进样口温度为200 ℃,进样体积为1 μL。检测器参数:温度300 ℃,尾吹气流量24 mL·min−1。GC的具体升温程序为:初始温度是34 ℃,保持6 min。然后以14 ℃·min−1升至70 ℃,保持0。最后以50 ℃·min−1升至200 ℃,保持2 min。后运行210 ℃,保持3 min。综合毒性指标采用细胞毒性指数(CTI)进行评估[19, 27],具体计算方法如式(1)所示,各种DBP的细胞毒性见表1所示。

式中,Cx为DBP的浓度(mol·L−1);LC50x为DBP的细胞毒性(mol·L−1).

-

预氧化时间对DBPs生成的影响见图1。在PMS预氧化过程中,TCM、TCAL、DCAM和TCAM均被检测到,但是DCAN和TCAN未能检测到。PMS的氧化还原电位为1.75 V [28],具有一定的氧化性,因此可氧化Cl−为HOCl/OCl− [29],HOCl/OCl−和有机物发生化学反应生成DBPs [19]。

随着预氧化时间的增加,Tyr溶液和实际水样中TCM、TCAL、DCAM和TCAM的浓度增加。预氧化时间从0.5 h增加至2.5 h时,Tyr溶液中TCM、TCAL、DCAM和TCAM的浓度分别从5.0、1.0、1.0、0.25 nmol·L−1增加至18.1、5.0、4.3、1.55 nmol·L−1。随着预氧化时间的增加,HOCl/OCl−浓度增加[30],HOCl/OCl−会和有机物发生化学反应生成DBPs。因此,随着预氧化时间的增加,DBPs浓度增加[27]。

-

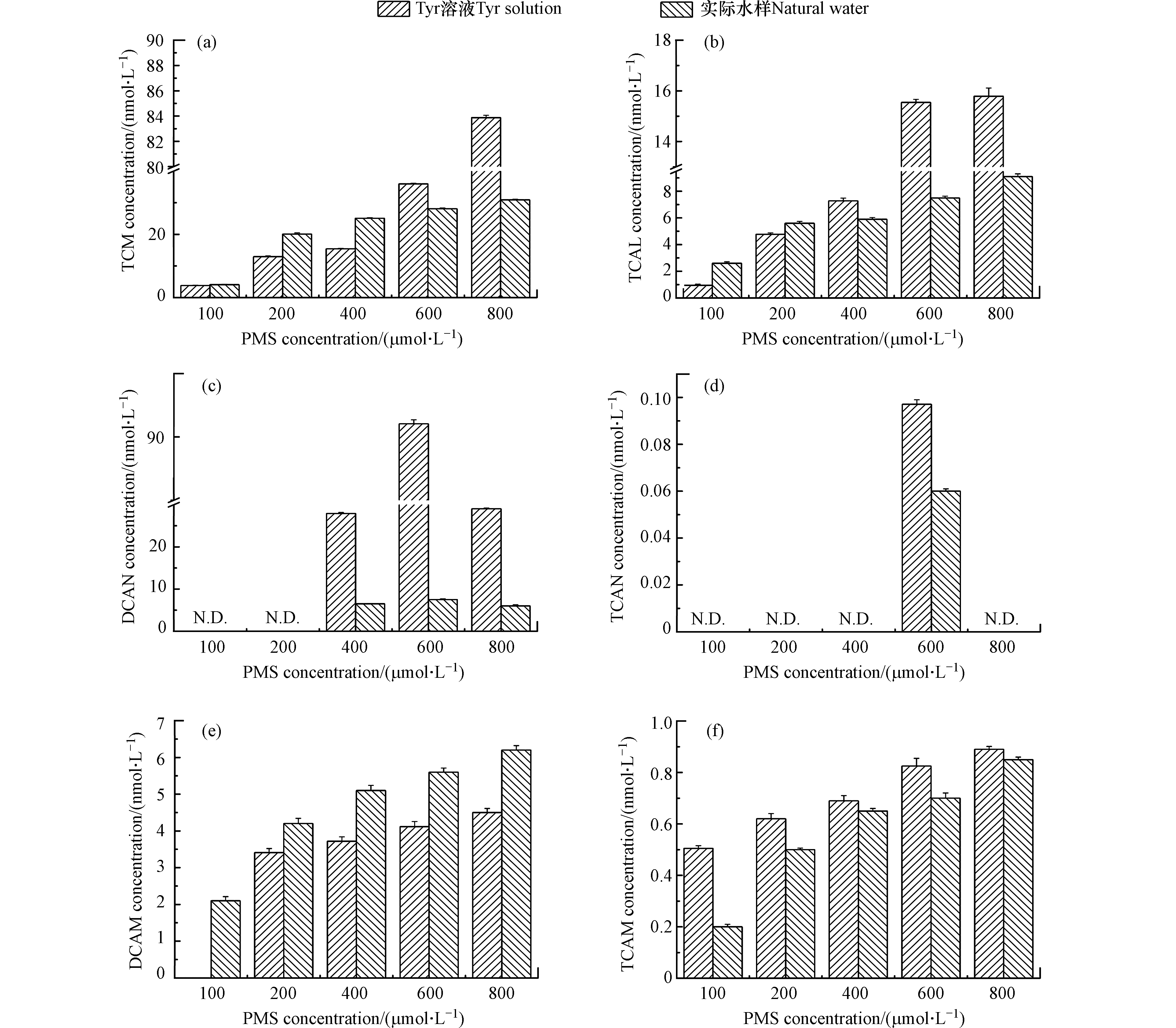

PMS浓度对DBPs生成的影响如图2所示。随着预氧化剂PMS的增加,Tyr溶液和实际水样中TCM、TCAL、DCAM、TCAM的浓度增加。PMS从100 µmol·L−1增加至800 µmol·L−1时,Tyr溶液中TCM、TCAL、DCAM、TCAM的浓度分别从3.8、0.9、0、0.5 nmol·L−1增加至83.9、15.8、4.5、0.9 nmol·L−1。研究表明,随着PMS浓度的增加,HOCl/OCl−浓度增加[30]。在HOCl/OCl−存在时,TCM是一个稳定的产物且不会发生水解[31]。DCAN和TCAN不稳定能够转化为DCAM和TCAM [32],且随着HOCl/OCl−浓度的增加,DCAN和TCAN的水解速度加快[33]。因此,随着PMS浓度的增加,TCM、TCAL、DCAM和TCAM的浓度增加。

随着PMS浓度的增加,Tyr溶液和实际水样中DCAN和TCAN的浓度先增加后降低。PMS浓度从100 µmol·L−1增加至800 µmol·L−1时,Tyr溶液中DCAN和TCAN的浓度先分别增加至91.1 nmol·L−1和0.097 nmol·L−1,然后降低至29.2 nmol·L−1和0。研究表明,DCAN和TCAN不稳定且能够发生水解[32],随着HOCl/OCl−浓度的增加,DCAN和TCAN的水解速度加快[33]。因此,随着PMS浓度的增加,DCAN和TCAN的浓度先增加后降低。

-

Cl−浓度对DBPs生成的影响如图3所示。随着Cl−浓度的增加,Tyr溶液中TCM、TCAL、DCAM和TCAM的浓度增加。但是DCAN和TCAN未检测到。随着Cl−浓度的增加,Tyr溶液中TCM、TCAL、DCAM、TCAM的浓度分别从12.2、0.6、0、0.55 nmol·L−1增加至15.3、8.0、4.1、0.9 nmol·L−1。

研究表明随着Cl−浓度的增加,HOCl/OCl−浓度增加[30]。HOCl/OCl−会和有机物发生化学反应生成DBPs。因此,随着Cl−浓度的增加,TCM、TCAL、DCAM和TCAM的浓度增加。

-

pH对DBPs生成的影响如图4所示。随着pH的增加,Tyr溶液和实际水样中DBPs的浓度降低。pH从5增加到9时,Tyr溶液中TCM、TCAL、DCAN、TCAN、DCAM、TCAM的浓度分别从413.6、2448.1、980.1、1.2、9.9、1.5 nmol·L−1降低至2.1、1.2、0、0、0.8、0.5 nmol·L−1。

pH对DBPs浓度的影响可以归结于以下几个原因:(1)pH影响PMS的分解及形态,PMS在低pH情况下降解速率很慢,随着pH的增加,PMS的降解速率增加。当pH为9.5时,PMS的含量只有原来的44% [34],因此,随着pH的增加,PMS浓度降低;(2)随着pH的增加,HOCl/OCl−浓度降低[30];(3)随着pH的增加,TCAL的水解速率增加,因此随着pH的增加,TCAL的浓度降低[35];(4)HANs的稳定性受pH的影响,且水解速率随着pH的增加而增加[33, 36]。因此,随着pH的增加,DBPs的浓度降低。

-

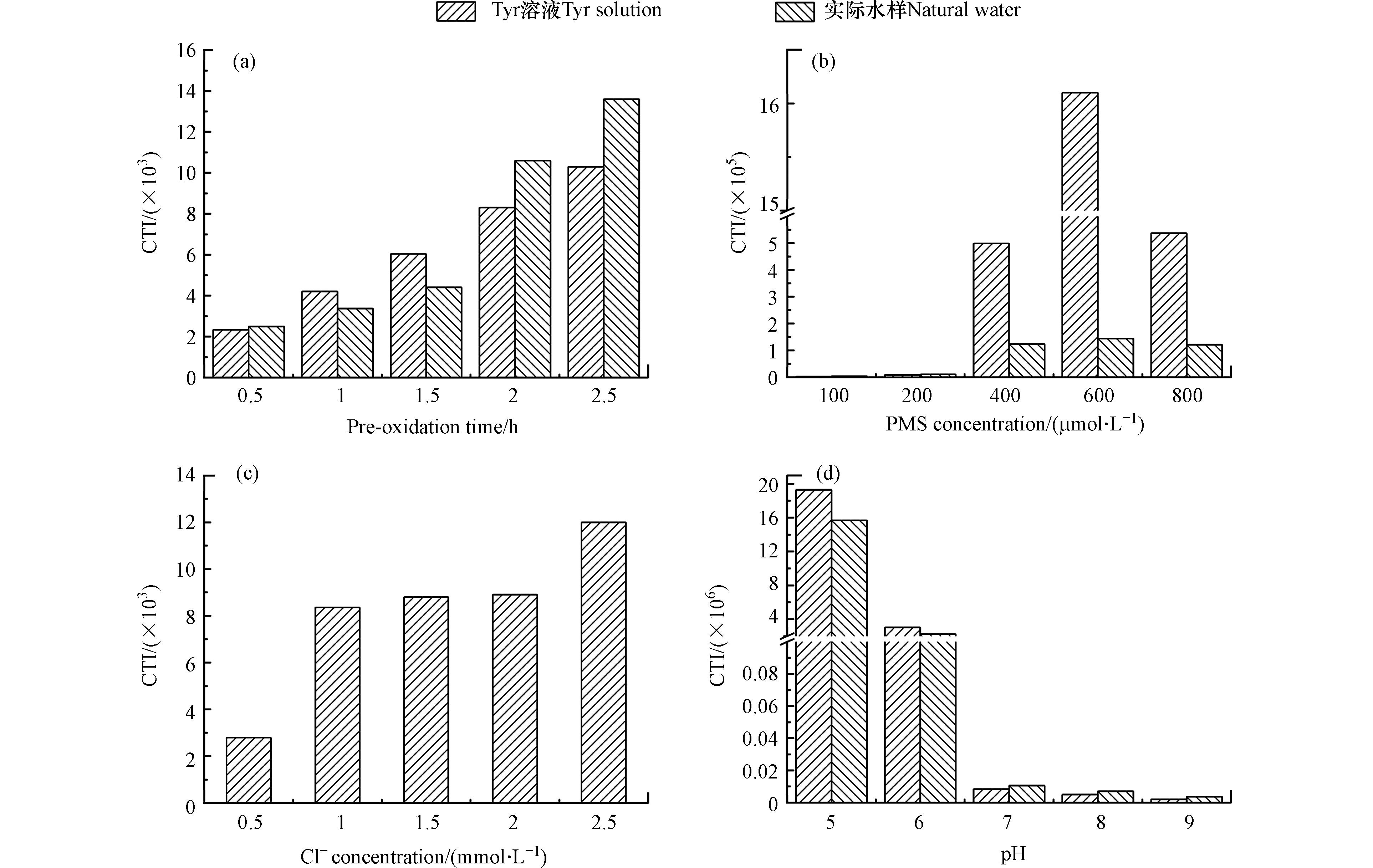

预氧化时间、PMS浓度、Cl−浓度和pH对CTI的影响如图5所示。随着预氧化时间的增加,Tyr溶液和实际水样中细胞毒性增加。预氧化时间从0.5 h增加至2.5 h时,Tyr溶液中细胞毒性从2.34×103增加至1.03×104。随着PMS浓度的增加,Tyr溶液和实际水样中细胞毒性先增加后降低。PMS从100 µmol·L−1增加至800 µmol·L−1时,Tyr溶液中细胞毒性先增加至1.61×106,然后降低至5.37×105。随着Cl−浓度的增加,Tyr溶液细胞毒性增加。Cl−从0.5 mmol·L−1增加至2.5 mmol·L−1时,Tyr溶液中细胞毒性从2.79×103增加至1.20×104。随着pH的增加,Tyr溶液和实际水样中细胞毒性降低。pH从5增加至9时,Tyr溶液中细胞毒性从1.93×107降低至2.02×103。

随着预氧化时间和Cl−浓度的增加,DBPs的浓度增加,因此细胞毒性增加。随着PMS浓度的增加,尽管TCM、TCAL、DCAM和TCAM的浓度增加,但是DCAN和TCAN的浓度先增加后降低。DCAN和TCAN的细胞毒性明显高于TCM、TCAL、DCAM和TCAM [37]。如图6所示,当DCAN和TCAN存在时,DCAN和TCAN对细胞毒性的贡献总和明显高于TCM、TCAL、DCAM和TCAM对细胞毒性的贡献总和。因此,随着PMS浓度的增加,细胞毒性先增加后降低。随着pH的增加,DBPs的浓度降低,因此随着pH的增加,细胞毒性降低。

-

(1)PMS预氧化过程中能够产生DBPs,随着预氧化时间及Cl−浓度的增加,DBPs的浓度增加。

(2)随着PMS浓度的增加,TCM、TCAL、DCAM和TCAM的浓度增加,但是DCAN和TCAN的浓度先增加后降低。随着pH的增加,DBPs的浓度降低。

(3)随着预氧化时间及Cl−浓度的增加,细胞毒性增加。随着PMS浓度的增加,细胞毒性先增加后降低。随着pH的增加,细胞毒性降低。

(4)当PMS作为预氧化剂时,在保证预氧化效果的同时,应该缩短预氧化时间,降低原水中Cl−浓度,同时提高预氧化时的pH,来降低DBPs浓度和毒性。

单过硫酸盐预氧化体系中消毒副产物的生成特性

Disinfection byproduct formation during peroxymonosulfate pre-oxidation process

-

摘要: 单过硫酸盐(PMS)作为预氧化剂,在预氧化过程中能够去除微污染物。但是PMS也能够氧化氯离子(Cl-)为有效氯(HOCl/OCl-)。HOCl/OCl-会和有机物发生反应生成消毒副产物(DBPs)。DBPs具有致畸、致癌和致突变的特性。然而,有关PMS预氧化过程中DBPs生成特性的研究相对较少。本文考察了预氧化时间、PMS浓度、Cl-浓度和pH对DBPs浓度和细胞毒性(CTI)的影响。研究结果表明,随着预氧化时间以及Cl-浓度的增加,DBPs浓度和CTI增加。随着PMS浓度的增加,三氯甲烷、水合三氯乙醛、二氯乙酰胺和三氯乙酰胺的浓度增加,但是二氯乙腈、三氯乙腈的浓度和CTI先增加后降低。随着pH的增加,DBPs浓度和CTI降低。综合而言,在PMS预氧化过程中,在满足预氧化效果的同时,应缩短预氧化时间,降低原水中Cl-浓度,同时提高pH,来降低DBPs浓度和毒性。Abstract: Peroxymonosulfate (PMS) is used as the pre-oxidant, which can remove effectively micropollutants during pre-oxidation process. However, PMS can also convert chloride (Cl-) to reactive chlorine (HOCl/OCl-). HOCl/OCl- can react with organic matter and then generate disinfection byproducts (DBPs). DBPs have teratogenic, carcinogenic and mutagenic properties. Few studies investigated the formation of DBPs during the PMS pre-oxidation process. This study investigated effects of pre-oxidation time, PMS concentration, Cl- concentration and pH on the formation of DBPs and cytotoxicity index (CTI). Results showed that DBPs concentrations and CTI increased as pre-oxidation time and Cl- concentration increased. The concentrations of trichloromethane, trichloroacetaldehy, dichloroacetamide and trichloroacetamide increased as the PMS concentration increased, while the concentrations of dichloroacetonitrile and trichloroacetonitrile, and CTI first increased and then decreased. DBPs concentrations and CTI decreased as the pH increased. In general, under the condition of ensuring requirement of pre-oxidation, the pre-oxidation time should be reduced to reduce DBPs concentrations and toxicity during PMS pre-oxidation process. Furthermore, Cl- concentration in water should be reduced and pH should increase during PMS pre-oxidation process.

-

Key words:

- peroxymonosulfate /

- pre-oxidation /

- disinfection byproduct /

- tyrosine /

- chloride

-

-

表 1 DBPs的细胞毒性

Table 1. The cytotoxicity of DBPs

DBP种类 Type of DBP TCM TCAL DCAN TCAN DCAM TCAM 细胞毒性LC50x/(mol·L−1) 104 860 175 6250 521 488 -

[1] ZHANG H, IHARA M O, NAKADA N, et al. Biological activity-based prioritization of pharmaceuticals in wastewater for environmental monitoring: G protein-coupled receptor inhibitors [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2020, 54(3): 1720-1729. [2] MEYER M F, POWERS S M, HAMPTON S E. An evidence synthesis of pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) in the environment: Imbalances among compounds, sewage treatment techniques, and ecosystem types [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2019, 53(22): 12961-12973. [3] WANG Y F, JING B H, WANG F L, et al. Mechanism Insight into enhanced photodegradation of pharmaceuticals and personal care products in natural water matrix over crystalline graphitic carbon nitrides [J]. Water Research, 2020, 180: 115925. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.115925 [4] CHO K, AN B M, SO S, et al. Simultaneous control of algal micropollutants based on ball-milled powdered activated carbon in combination with permanganate oxidation and coagulation [J]. Water Research, 2020, 185: 116263. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116263 [5] LIU B, ZHU T T, LIU W K, et al. Ultrafiltration pre-oxidation by boron-doped diamond anode for algae-laden water treatment: Membrane fouling mitigation, interface characteristics and cake layer organic release [J]. Water Research, 2020, 187: 116435. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116435 [6] LIN S Y, YU X, FANG J Y, et al. Influences of the micropollutant erythromycin on cyanobacteria treatment with potassium permanganate [J]. Water Research, 2020, 177: 115786. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.115786 [7] YANG Y, BANERJEE G, BRUDVIG G W, et al. Oxidation of organic compounds in water by unactivated peroxymonosulfate [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52(10): 5911-5919. [8] LEE J, von GUNTEN U, KIM J H. Persulfate-based advanced oxidation: Critical assessment of opportunities and roadblocks [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2020, 54(6): 3064-3081. [9] GUO Y Q, LIANG H, BAI L M, et al. Application of heat-activated peroxydisulfate pre-oxidation for degrading contaminants and mitigating ultrafiltration membrane fouling in the natural surface water treatment [J]. Water Research, 2020, 179: 115905. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.115905 [10] 谢鹏超, 岳思阳, 邹景, 等. 四种预氧化方式对AOC及消毒副产物影响的对比 [J]. 中国给水排水, 2015, 31(7): 6-9. doi: 10.19853/j.zgjsps.1000-4602.2015.07.002 XIE P C, YUE S Y, ZOU J, et al. Comparison of effects of four different preoxidation processes on formation of assimilable organic carbon and disinfection by-products [J]. China Water & Wastewater, 2015, 31(7): 6-9(in Chinese). doi: 10.19853/j.zgjsps.1000-4602.2015.07.002

[11] QI J, LAN H C, MIAO S Y, et al. KMnO4-Fe(II) pretreatment to enhance Microcystis aeruginosa removal by aluminum coagulation: Does it work after long distance transportation? [J]. Water Research, 2016, 88: 127-134. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2015.10.004 [12] XIE P C, CHEN Y Q, MA J, et al. A mini review of preoxidation to improve coagulation [J]. Chemosphere, 2016, 155: 550-563. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.04.003 [13] LI X Y, PI Y H, WU L Q, et al. Facilitation of the visible light-induced Fenton-like excitation of H2O2 via heterojunction of g-C3N4/NH2-Iron terephthalate metal-organic framework for MB degradation [J]. Applied Catalysis B:Environmental, 2017, 202: 653-663. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2016.09.073 [14] SUN Q, LIU M, LI K Y, et al. Synthesis of Fe/M (M = Mn, Co, Ni) bimetallic metal organic frameworks and their catalytic activity for phenol degradation under mild conditions [J]. Inorganic Chemistry Frontiers, 2017, 4(1): 144-153. doi: 10.1039/C6QI00441E [15] ANIPSITAKIS G P, DIONYSIOU D D. Radical generation by the interaction of transition metals with common oxidants [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2004, 38(13): 3705-3712. [16] GUAN Y H, MA J, LI X C, et al. Influence of pH on the formation of sulfate and hydroxyl radicals in the UV/peroxymonosulfate system [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2011, 45(21): 9308-9314. [17] WEN G, WANG S B, WANG T, et al. Inhibition of bromate formation in the O3/PMS process by adding low dosage of carbon materials: Efficiency and mechanism [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2020, 402: 126207. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.126207 [18] CHEN T T, YU Z Y, XU T, et al. Formation and degradation mechanisms of CX3R-type oxidation by-products during cobalt catalyzed peroxymonosulfate oxidation: The roles of Co3+ and SO4·- [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2021, 405: 124243. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124243 [19] CHEN T T, DONG S K, GUO X P, et al. Dissolved organic carbon removal and CX3R-type byproduct formation during the peroxymonosulfate pre-oxidation followed by coagulation [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2021, 421: 129654. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2021.129654 [20] 李忠禹, 彭健伟, 文怡心, 等. 饮用水含氮与含碳消毒副产物的生成潜能及其毒性 [J]. 环境科学学报, 2021, 41(9): 3401-3407. doi: 10.13671/j.hjkxxb.2020.0485 LI Z Y, PENG J W, WEN Y X, et al. Formation potential and estimated toxicity of nitrogenous and carbonaceous disinfection byproducts in drinking water [J]. Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae, 2021, 41(9): 3401-3407(in Chinese). doi: 10.13671/j.hjkxxb.2020.0485

[21] WAGNER E D, PLEWA M J. CHO cell cytotoxicity and genotoxicity analyses of disinfection by-products: An updated review [J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2017, 58: 64-76. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2017.04.021 [22] LIU J Q, ZHANG X R. Comparative toxicity of new halophenolic DBPs in chlorinated saline wastewater effluents against a marine alga: Halophenolic DBPs are generally more toxic than haloaliphatic ones [J]. Water Research, 2014, 65: 64-72. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.07.024 [23] 洪涵璐, 赵伟, 尹金宝. 饮用水消毒副产物基因毒性与致癌性研究进展 [J]. 环境监控与预警, 2020, 12(5): 36-48. HONG H L, ZHAO W, YIN J B. A review on the genotoxicity and carcinogenicity of disinfection by-products in drinking water [J]. Environmental Monitoring and Forewarning, 2020, 12(5): 36-48(in Chinese).

[24] YAO D C, CHU W H, BOND T, et al. Impact of ClO2 pre-oxidation on the formation of CX3R-type DBPs from tyrosine-based amino acid precursors during chlorination and chloramination [J]. Chemosphere, 2018, 196: 25-34. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.12.143 [25] SHAH A D, MITCH W A. Halonitroalkanes, halonitriles, haloamides, and N-nitrosamines: A critical review of nitrogenous disinfection byproduct formation pathways [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2012, 46(1): 119-131. [26] RAM N M. A review of the significance and formation of chlorinated N-organic compounds in water supplies including preliminary studies on the chlorination of alanine, tryptophan, tyrosine, cytosine, and syringic acid [J]. Environment International, 1985, 11(5): 441-451. doi: 10.1016/0160-4120(85)90227-2 [27] DING S K, CHU W H, BOND T, et al. Formation and estimated toxicity of trihalomethanes, haloacetonitriles, and haloacetamides from the chlor(am)ination of acetaminophen [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2018, 341: 112-119. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.07.049 [28] WACŁAWEK S, LUTZE H V, GRÜBEL K, et al. Chemistry of persulfates in water and wastewater treatment: A review [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2017, 330: 44-62. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2017.07.132 [29] CHEN T T, WANG R, ZHANG A H, et al. Peroxymonosulfate/chloride disinfection versus sodium hypochlorite disinfection in terms of the formation and estimated cytotoxicity of CX3R-type disinfection by-products under the same dose of free chlorine [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2020, 391: 123557. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2019.123557 [30] HOU S D, LING L, DIONYSIOU D D, et al. Chlorate formation mechanism in the presence of sulfate radical, chloride, bromide and natural organic matter [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52(11): 6317-6325. [31] LIANG L, SINGER P C. Factors influencing the formation and relative distribution of haloacetic acids and trihalomethanes in drinking water [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2003, 37(13): 2920-2928. [32] CHU W H, GAO N Y, DENG Y. Formation of haloacetamides during chlorination of dissolved organic nitrogen aspartic acid [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2010, 173(1/2/3): 82-86. [33] YU Y, RECKHOW D A. Kinetic analysis of haloacetonitrile stability in drinking waters [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2015, 49(18): 11028-11036. [34] LI Z B, CHEN Z, XIANG Y Y, et al. Bromate formation in bromide-containing water through the cobalt-mediated activation of peroxymonosulfate [J]. Water Research, 2015, 83: 132-140. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2015.06.019 [35] DEBORDE M, von GUNTEN U. Reactions of chlorine with inorganic and organic compounds during water treatment−Kinetics and mechanisms: A critical review [J]. Water Research, 2008, 42(1/2): 13-51. [36] GLEZER V, HARRIS B, TAL N, et al. Hydrolysis of haloacetonitriles: Linear free energy relationship, kinetics and products [J]. Water Research, 1999, 33(8): 1938-1948. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(98)00361-3 [37] PLEWA M J, MUELLNER M G, RICHARDSON S D, et al. Occurrence, synthesis, and mammalian cell cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of haloacetamides: An emerging class of nitrogenous drinking water disinfection byproducts [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2008, 42(3): 955-961. -

下载:

下载: