-

氯化石蜡(chlorinated paraffins, CPs)是由氯化度为30%—70%的正构烷烃组成的工业混合物[1],化学式通式为CnH2n+2-zClz[2]. 一般按照碳链长度可以分为短链氯化石蜡(short-chain chlorinated paraffins, SCCPs),中链氯化石蜡(medium-chain chlorinated paraffins, MCCPs)和长链氯化石蜡(long-chain chlorinated paraffins, LCCPs),碳原子数量分别为C10—13、C14—17和C18—20,有时还有超短链氯化石蜡(very short-chain chlorinated paraffins, vSCCPs, C6—9)和超长链氯化石蜡(very long-chain chlorinated paraffins, vLCCPs, C21—30)的区分[3-4]. CPs具有阻燃性、耐化学性和耐水性等良好的物理化学性质,常被用作PVC、橡胶和表面涂料等的增塑剂、黏合剂、密封剂、阻燃剂、金属加工润滑油和皮革加脂剂[5-6]. 在过去15年中,CPs的全球产量大幅增加[7]. 中国是CPs的主要生产国和消费国[8],2017年CPs产量为100万吨[9].

随着大量生产和广泛应用,CPs不可避免地在生产、运输和使用过程中释放到环境中[10]. CPs已经在多种环境介质中被检测出,包括空气[11]、水[12]、土壤[13]和沉积物[14]. 因为具有持久性[15]、长距离迁移性[16]、生物积累性[17]和生物毒性[18],SCCPs在2017年5月被列入到《斯德哥尔摩公约》的附件A中[19]. CPs具有生物蓄积性,能够进入到动物体内[20]和人体[21-22]. 大量实验结果表明,SCCPs具有肝毒性[23]、发育毒性[24]、内分泌和代谢干扰作用[25]以及免疫调节作用[26]. 一项针对CPs暴露对细胞代谢影响的研究指出,MCCPs和LCCPs也具有生物毒性[27]. 因此,CPs进入人体会产生健康危害,对CPs的人体内外暴露研究尤为重要.

本文综述了近20年国内外CPs人体暴露的相关研究,对CPs的外部暴露途径及人体内CPs赋存水平进行总结,为CPs的健康风险评估提供了科学依据.

-

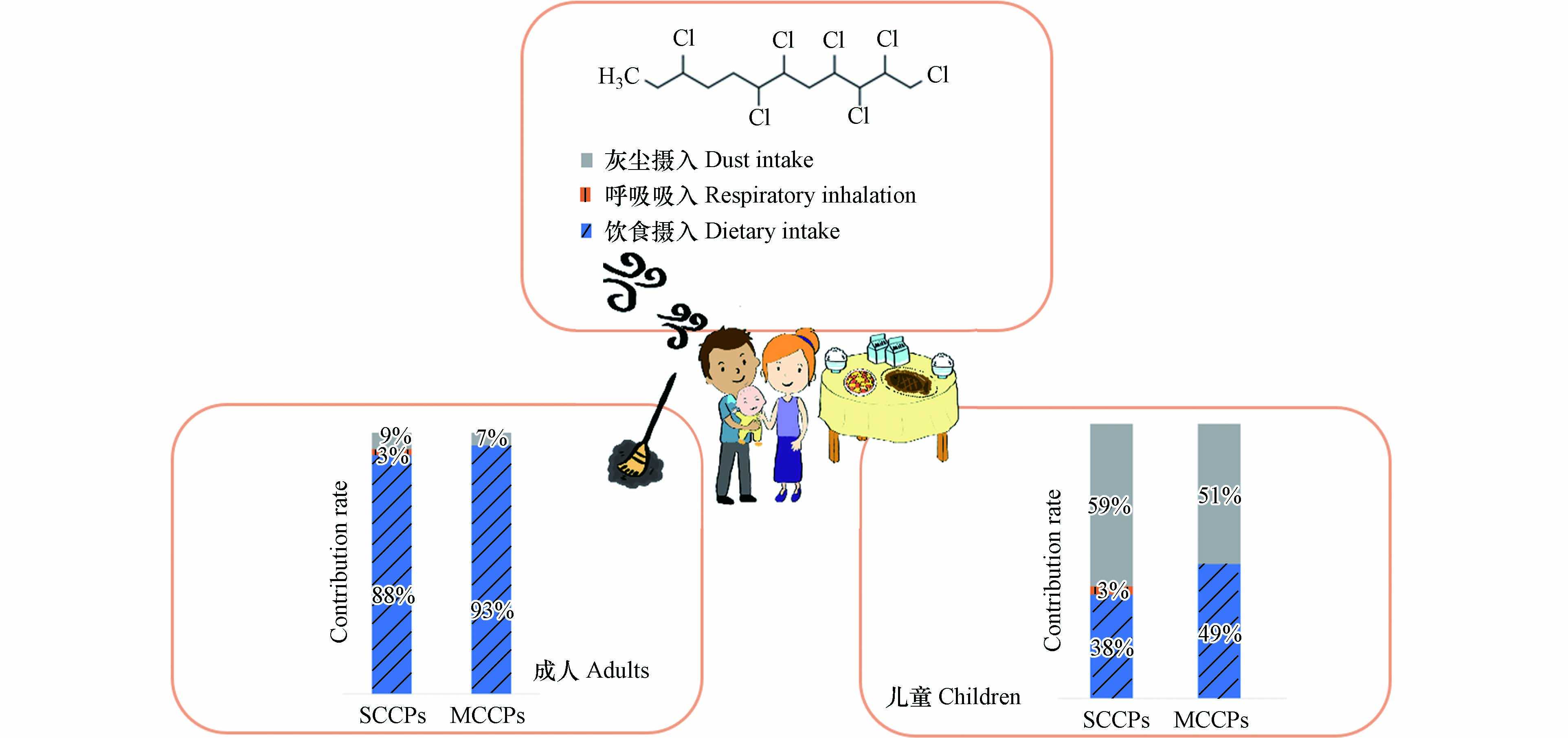

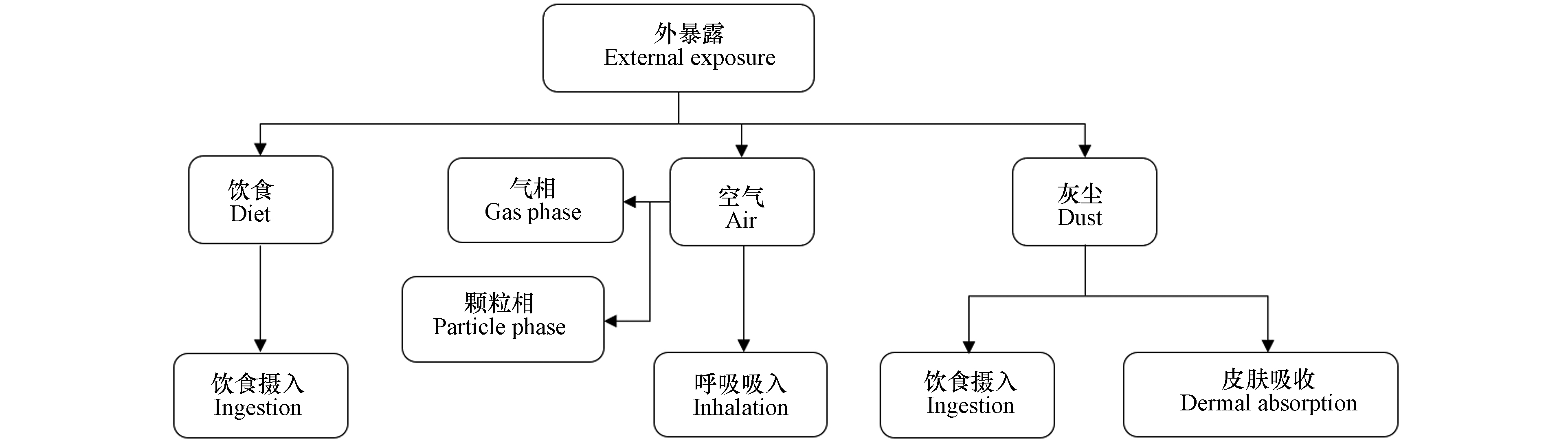

食物和受污染的室内环境是人类接触CPs的最相关来源[28]. 已经有研究表明,一般人群CPs的外部暴露途径可以分为饮食、空气和灰尘摄入[10, 29-31]. 与以上3种暴露途径相比,饮用水摄入的外部暴露几乎可以忽略不计,因为CPs是亲脂性很强的化合物[29, 32]. CPs经不同途径产生的人体外部暴露及贡献率分别如图1和图2所示.

-

饮食摄入是CPs人体暴露的主要途径[32-34]. 有研究表明,饮食摄入是一般居民SCCPs的主要暴露途径,占人体总暴露量的85%[35]. 北京市成年人膳食摄入的SCCPs和MCCPs量分别占日均摄入量的88%和93%[29]. 汇总的文献数据表明,不同年份的食物样本中测量的CPs水平在不同采样地点甚至国家内部都有很大差异,说明CPs的暴露风险也是不同的. 可能是由于地区污染水平的变化以及地理条件、饮食习惯、文化和经济水平的差异造成的[36-37]. Fan等[38]对过去30年发表的有关中国SCCPs的膳食风险的文献进行了研究,利用不同食品类别中的SCCPs浓度、消耗率和体重计算出中国成年人通过膳食暴露SCCPs的每日估计摄入量为(2.5 ± 1.6)μg·kg−1·d−1 bw. 文献报道的膳食CPs暴露评估如表1所示.

Harada等[39]对在20世纪90年代和2007—2009年来自日本和韩国成年人的24小时混合食物样本中的SCCPs水平进行了测定. 日本人均SCCPs总膳食摄入量在10年内没有变化,几何平均数为54 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw,首尔的成年女性SCCPs的每日估计摄入量是ND—50 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw[39]. 日本第一次市场菜篮子研究指出,日本成年人(30—39岁)SCCPs的每日估计摄入量为110 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw(第50分位数)[40]. 该研究还指出,1岁女幼儿的SCCPs每日暴露量的第95分位数为680 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw,造成该种现象的原因可能是婴幼儿体重较轻,每单位体重的食物消耗量往往比成年人高[40-41]. 德国南部的市场菜篮子研究表明,婴儿和幼儿每天每公斤体重的CPs暴露量最高,平均值分别为960 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw和780 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw,主要来自于乳制品和油脂;成年人SCCPs和MCCPs的每日暴露量分别为100—420 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw和100—840 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw,主要来自于油脂、面包和乳制品[42]. 该研究还对餐馆的即食食品和总膳食样品进行SCCPs和MCCPs的饮食暴露评估,如果将这两种途径也考虑进去,成年人SCCPs和MCCPs的每日暴露量则分别为35—420 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw和22—840 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw [42]. 瑞典2015年的市场菜篮子调查报告指出,瑞典成年人ΣCPs的每日暴露量为60 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw,最主要的来源是糖[43]. 对SCCPs膳食暴露的主要贡献食物会因性别和年龄而异[41]. Lee等[41]对来自韩国的59种食品样品中的SCCPs进行了测定,并计算出韩国男性和女性成年人膳食中的SCCPs摄入量(中位数)分别为888 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw和781 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw,主要来源于肉类和乳制品,而婴儿/儿童和老年人(≥65岁)对SCCPs膳食暴露的主要贡献食物分别是乳制品和谷物.

中国于2011—2019年由国家食品安全风险评估中心牵头组织了总膳食样品污染物的调查. 中国第5次总膳食调查的结果表明,中国成年人通过摄食水产品、谷类和豆类的SCCPs每日估计摄入量分别为871.9 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw[34]、5185 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw[44]和529 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw[44],MCCPs每日估计摄入量分别为54.6 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw[34]、3093 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw[44]和295 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw[44]. 其中,中国河北、广西、四川、黑龙江、辽宁和浙江省谷物中MCCPs的EDIs大于每日耐受摄入量(tolerable daily intakes, TDIs, 100 μg·kg−1·d−1 bw)[45],说明这些地区谷物中的MCCPs可能会对居民的健康造成危害[44]. Cui等[33]在第6次中国总膳食调查中,对南方九省的谷物、蔬菜、薯类、豆类、鸡蛋、牛奶、肉类和水产食品中的SCCPs和MCCPs的人体暴露情况进行了研究. 中国南方地区一般人群通过总膳食的SCCPs和MCCPs的估计每日摄入量平均值分别为700 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw和470 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw,主要来自于谷物、蔬菜和肉类[33]. 中国南方地区成年男性水产品的SCCPs和MCCPs估计膳食摄入量分别为45 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw和27 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw,谷类的SCCPs和MCCPs估计膳食摄入量分别为170 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw和130 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw,豆类的SCCPs和MCCPs估计膳食摄入量分别为91 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw和31 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw [33]. Weber[46]在2017年提出,需要对食用动物/肉类中POPs的风险进行更系统的评估. 在中国第5次和第6次总膳食调查中,成年男性摄食肉类的SCCPs的每日估计摄入量分别为190 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw[36]和110 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw[33],MCCPs的每日估计摄入量分别为8.1 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw[36]和100 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw [33]. 在中国通过肉类消费产生的SCCPs和MCCPs暴露不会对人类健康构成重大风险. 与第5次总膳食调查相比,除了肉类中的MCCPs以外,第6次总膳食调查中的水产品、谷类、豆类和肉类的SCCPs和MCCPs的人体估计每日摄入量都低于第5次总膳食调查的结果.

另有其他文献报道了我国膳食CPs的暴露量. 中国华北地区SCCPs的膳食暴露量估计值为1138.5—3795.8 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw [47]. 其中,膳食暴露水平最高的城市是邢台市,主要原因是工业污染严重[47]. 除了区域性的研究以外,还有针对北京市和济南市的总膳食调查. 1993—2009年,北京市成年人的SCCPs膳食暴露水平上升了2个数量级[39]. 而2016年北京市成年人SCCPs总膳食摄入量的几何平均数为611 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw,与2009年的结果相当(620 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw),MCCPs总膳食摄入量的范围是153—1307 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw [29, 39]. 针对济南市超市生鲜产品(包括肉类、水产品、蔬菜、水果和谷物)中SCCPs的膳食暴露的研究结果表明,居民通过膳食摄入的SCCPs的估计每日摄入量为3109 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw [35]. Ding等[48]的结果表明,济南市成人饮食中SCCPs、MCCPs和LCCPs的EDI中位数分别为1987.1、949.5 、287.9 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw,并呼吁人们重视中国食品中的LCCPs污染.

除了总膳食调查之外,还有对婴幼儿食品以及食用油、茶叶、牛奶、杯装方便面、鱼类等单一种类食品的研究. 中国1—12个月婴儿通过配方奶粉的SCCPs和MCCPs每日摄入量分别为182—354 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw和145—282 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw,7—12个月婴儿通过摄入谷物和果泥的SCCPs暴露量(第90分位数)分别为46 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw和 67 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw,MCCPs暴露量(第90分位数)分别为26 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw 和 28 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw [49]. Krätschmer等[50]计算出德国3个月婴儿每天通过婴儿配方奶粉摄入SCCPs的范围为97—360 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw. 在中国部分地区,麻花、芝麻籽等油炸食品占SCCPs总膳食摄入量的相当大比例(10.2%),食用油是中国居民从饮食中接触SCCPs的来源之一[51]. Cao等[51]的研究表明,通过食用油的SCCPs平均摄入量是212 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw,约占SCCPs总摄入量的32.2%. 中国普通人群食用油中SCCPs和MCCPs的平均摄入量分别为8.83 μg·kg−1·d−1 bw和6.09 μg·kg−1·d−1 bw,该摄入量随年龄的增加而减少[52]. 中国成年人通过茶叶摄入的SCCPs和MCCPs的日摄入量范围分别为0.79—113 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw和0.40—86.2 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw [53]. Dong等[54]的研究表明,根据推荐的日均牛奶摄取量200 g,内蒙古、河北、河南、山东和湖北省成年男性通过生牛奶摄入的SCCPs和MCCPs的估计暴露量的范围分别为62—270 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw和13—50 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw,不应忽视人体通过乳制品的SCCPs和MCCPs暴露. 人体通过杯装方便面的面条、调料和汤的SCCPs暴露量(第95分位数)分别为3222 、939 、23 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw,MCCPs分别为514 、77 、15 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw [55]. Huang等[56]收集了珠江三角洲及长三角地区经常消费的河鱼、养殖淡水鱼及海鱼,研究结果表明,上海市居民通过食用养殖淡水鱼和海水鱼的SCCPs摄入量分别为(49 ± 42)ng·kg−1·d−1 bw和(32 ± 16)ng·kg−1·d−1 bw,广东省居民通过食用河鱼的SCCPs摄入量为(47 ± 32)ng·kg−1·d−1 bw. 对于上海居民而言,考虑到SCCPs的负面影响,食用海鱼比食用养殖淡水鱼更安全[56]. Krätschmer等[57]的研究表明,20—75周岁的德国人通过鲑鱼对∑CPs的摄入量为4.6—35 ng·kg−1·w−1 bw.

电子垃圾是CPs的重要来源之一[58-59]. 因此,也有针对电子垃圾拆解场地附近饮食暴露的研究[32, 60]. Yuan等[61]调查了浙江省台州市电子垃圾拆解区稻米种子中的SCCPs,并计算出当地成人通过摄入稻米的SCCPs暴露量为26.4—297 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw,推测生活在电子垃圾拆解区的居民饮食中SCCPs的暴露风险更高. Zeng等[62]测定了从广东贵屿镇电子废物场收集的家庭生产鸡蛋和鹅蛋中的SCCPs含量,并分别估算了成人通过食用鸡蛋和鹅蛋对SCCPs的摄入量. 另一项研究对广东清远市某电子垃圾回收站附近的家庭生产的鸡蛋进行了分析,结果表明,成人和儿童对SCCPs和MCCPs的估计每日摄入量分别为11.8—11900 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw和3.62—11400 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw [60]. 其中,MCCPs的最大EDI(11.4 μg·kg−1·d−1 bw)是TDI(6 μg·kg−1·d−1 bw)的近2倍[60, 63]. Chen等[32]对广东省某大型电子垃圾回收工业园附近居民与从事电子垃圾回收工作的工人的SCCPs和MCCPs的粉尘和膳食暴露的综合影响进行了研究,该地区成人通过饮食摄入估算的SCCPs和MCCPs的摄入量分别为15400 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw和19500 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw,都高于其他地区人群的报告值. 将粉尘和饮食摄取暴露结合在一起,结果表明,SCCPs暴露中值比北京的一般人群高20倍左右,而MCCPs暴露中值比北京的一般人群高出约25倍[29, 32].

大多数报道CPs膳食摄入量的研究使用的是食物中CPs的浓度,没有考虑CPs的生物可及性. 这样可能会高估CPs的饮食摄入量[64]. Cui等[64]考虑了SCCPs的生物可及性后,重新计算了中国第5次总膳食调查中肉类和海鲜的EDI值,平均值分别为87 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw和336 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw(进食状态下)或104 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw和457 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw(未进食状态). 与未考虑SCCPs生物可及性的结果相比,EDI值显著下降[34, 36]. 未来应根据CPs的生物可及性进行更全面的膳食暴露评估.

-

人体可以通过吸入气相或颗粒物暴露于空气中的CPs,吸入的颗粒通常会通过黏液被摄入[66]. 空气分为室外空气和室内空气. 不同于含5—6环的多环芳烃等有机污染物,CPs在室内空气的气相和颗粒物中的浓度均高于室外相应值,原因是室内含CPs产品的使用,如油漆、涂料、皮革和橡胶制品等[67-70]. 同时,成年人在一天之中大约有9 h在工作场所,一半以上时间在住宅公寓,婴幼儿几乎整天都在住宅公寓[29]. 由于人类大部分时间在室内环境度过,多数研究针对的是室内空气和室内灰尘摄入的人体暴露.

室内空气的吸入已经被证明是CPs人体暴露的重要途径之一[71-72]. 成年人的吸入途径受粉尘摄入率的影响,占室内环境暴露的76% 或98%[30]. 瑞典婴幼儿∑CPs的体重标准化室内暴露估计值(0.49 μg·kg−1·d−1 bw)高于成年人(0.06 μg·kg−1·d−1 bw)[30]. 不同国家或地区对人体通过吸入室内空气的CPs暴露情况进行了监测,如表2所示. Sakhi等[72]分析了挪威2012年家庭和学校的室内空气样品,结果表明母亲和孩子的SCCPs空气吸入暴露量分别为26 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw和39 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw [72]. 挪威2013—2014年的研究表明,人体吸入vSCCPs、SCCPs、MCCPs和LCCPs的暴露量分别为0.073、1.6 、0.23 、0.0046 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw [71]. 除了SCCPs的空气吸入暴露量与灰尘摄入的暴露相当(1.1 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw)外,其他CPs都高于灰尘摄入的暴露量,vSCCPs的空气吸入暴露量是灰尘摄入(0.00069 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw)的100倍以上[71]. 在中国北京进行的一项研究中明确了CPs对人体的室内空气吸入暴露,人体吸入SCCPs的暴露量最高,1—<2岁的幼儿和21—<31岁的成人的暴露量分别为51.7 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw和20.6 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw,其次是MCCPs(幼儿:3.49 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw,成人:1.49 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw)[29]. 幼儿的CPs室内环境暴露水平高于成人的暴露水平. 中国室内的高暴露水平与近年来中国大量的生产和使用是一致的[8]. 有研究表明,个人空气样品(由室内居住者携带小型主动采样器收集)中的CPs水平高于室内空气,因此个人空气样品对CPs吸入暴露的评估值更加准确[71]. 除了气粒结合相以外,也有针对室内空气颗粒相中CPs人体暴露的研究. 已有研究表明,室内PM2.5暴露非常重要,约占室内CPs颗粒物暴露的93.8%[73]. Huang等[67]报道了北京市内不同粒径颗粒物中CPs的含量和分布,在室内空气中,CPs主要与直径为2.5 μm的颗粒有关. CPs在进入人体呼吸系统的过程中主要沉积在头部气道中[74]. CPs在人体呼吸道中的沉积与颗粒大小有关,随着碳链长度或氯含量的增加,细颗粒对人类呼吸道CPs区域沉积的贡献增加[75].

室外空气也是人类呼吸摄入CPs的重要来源,济南市成年人室外空气中SCCPs的年平均吸入暴露量估计值为1.75×10−4 mg·kg−1·d−1 bw[76]. 与室内空气相同,室外空气中的CPs也主要与PM2.5相关[67]. 有研究报道了中国北京、成都、兰州、武汉、太原、贵阳、新乡、广州、南京和上海等10座城市成年男性通过室外空气中PM2.5吸入SCCPs和MCCPs的暴露量范围分别为2.70×10−3—4.15×10−3 mg·kg−1·d−1 bw和2.53×10−3—3.90×10−3 mg·kg−1·d−1 bw[74]. 针对武汉市露天消费场所的颗粒物中CPs的人体暴露风险评估表明,CPs对人体健康的风险较低[77]. 颗粒物中的CPs浓度呈现季节性变化. 济南市PM2.5中冬季检测到的SCCPs浓度最高,夏季最低,原因是夏季较高的温度容易导致SCCPs从商业产品中挥发以及从颗粒物向气相转移[76]. 中国珠江三角洲室内空气的CPs暴露水平远高于室外空气[73],但现有的部分室外空气的人体暴露数据高于室内空气暴露,可能的原因为计算时未考虑普通人群的室外活动时间或采样点附近污染较重. Zhuo等[73]根据室内外颗粒物中的CPs浓度和人群室内外暴露时间,计算出珠江三角洲地区人群通过空气中PM2.5吸入估计的每日CPs摄入量为 8.1—24.6 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw[73],该数值与室内暴露数据接近.

-

已经有研究表明,灰尘摄入和皮肤渗透在人体接触CPs中起重要作用[30-31, 78]. 对幼儿而言,灰尘的摄入是室内灰尘暴露的主要途径,这可能与幼儿经常性的手口接触行为有关[29, 79]. 人体通过灰尘摄入和皮肤吸收造成的CPs暴露的研究现状如表3所示. 挪威成年人通过灰尘摄入vSCCPs、SCCPs、MCCPs和LCCPs的每日估计暴露量分别为0.00069、1.1、0.70、0.090 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw [71]. 北京市成年人通过灰尘摄入的SCCPs和MCCPs的每日估计摄入量分别为179 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw和93.3 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw [29],远高于挪威的研究结果[71]. 北京市幼儿通过灰尘摄入的SCCPs和MCCPs的每日估计摄入量分别为1519 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw和613 ng·kg−1·d−1 bw,远高于成人[29],与澳大利亚的情况一致[78]. 在大连某购物中心内灰尘对人群的暴露研究中,成年人来自皮肤接触的CPs量占总摄入量的82.4%—90.4%,说明灰尘的皮肤渗透是成年人更主要的暴露途径[79],与Chen等[32]的研究结果一致. Liu等[80]的研究表明成人在室内环境中通过灰尘摄入的日暴露剂量比皮肤吸收高2.8倍. 两个研究结果不同的原因可能是采样点性质的不同,前者是购物中心,后者是公寓的客厅. 不同室内环境中的人体暴露可能会有所不同,因为使用的含有 CPs的产品不同[30]. Du等[31]的研究结果表明,灰尘中CPs的分子大小、营养成分和灰尘性质等会对CPs的生物可给性产生影响. 目前的研究结果都表明,室内灰尘暴露对一般人群没有明显的健康风险,但人类在室内环境中暴露于CPs仍需要进一步的关注和详细的研究. 与其他POPs相比,人们通过室内灰尘接触到SCCPs和MCCPs的剂量要高得多[79].

-

由于母乳的脂质含量较高且样品采集过程具有无创性,因此在检测CPs等亲脂性化合物方面要优于血清[81]. Krätschmer等[81]报道了2012—2019年亚洲、非洲、大洋洲、欧洲和南美洲的53个国家的母乳样本中CPs的浓度范围为23—700 ng·g−1 lw,欧洲和南美洲国家母乳中的CPs浓度低于另外3个洲的国家. Surenjav等[82]的研究表明,蒙古国母乳中SCCPs的浓度为164 ng·g−1 lw,柬埔寨、泰国和越南3个国家母乳中SCCPs的浓度范围为18.3—89.0 ng·g−1 lw. 加拿大哈德逊海峡居住的妇女的母乳中SCCPs的脂肪含量为11—17 ng·g−1 lw [83]. 英国母乳中SCCPs和MCCPs的浓度范围分别是49—820 ng·g−1 lw和6.2—320 ng·g−1 lw [84]. 瑞典和挪威的母乳样品中SCCPs、MCCPs和LCCPs的浓度范围分别为<LOD—120 ng·g−1 lw、<LOD—311 ng·g−1 lw和<LOD—29.0 ng·g−1 lw [85].

此前已经有文章对2001—2020年中国母乳中POPs的水平和概况及其对母乳喂养婴儿的潜在健康风险进行了综述[86]. 结果表明,中国在2007—2018年采集的母乳中∑CPs的浓度为1364 ng·g−1 lw[86]. 中国母乳中的SCCPs浓度高于国外现有的研究结果,MCCPs浓度是英国、瑞典和瑞士研究结果的2—6倍,LCCPs浓度高于挪威和瑞典的研究结果[84-86]. 值得注意的是,两项针对中国母乳中CPs的大规模研究的结果表明,中国2007—2011年采集的母乳中SCCPs的浓度远高于MCCPs,最高占总 CPs浓度的90%[87-88],而2015—2016年在上海市和江西省的研究显示,母乳中MCCPs的浓度高于SCCPs[85]. 母乳中MCCPs浓度在总CPs浓度中占比增高的趋势在国外的研究中也有体现. 英国2006年的研究结果表明SCCPs明显占主导地位[84],而Krätschmer等[81]采集的2012—2019年的大部分样品中MCCPs浓度等于或高于SCCPs(SCCPs/MCCPs比率的中位数为0.7). 母乳中较高的 MCCPs 浓度表明母亲的 SCCPs 累积暴露量低于MCCPs 的累积暴露量[81],但也有部分地区的研究结果与上述趋势不一致,如绍兴市2010年的母乳样品(MCCPs浓度高于SCCPs)[85]和四川省2018年的母乳样品(SCCPs浓度高于MCCPs)[89].

Xu等[90]的最新研究表明,2017年中国城市和农村母乳中的SCCPs的浓度分别为393 ng·g−1 lw和525 ng·g−1 lw,MCCPs的浓度分别是472 ng·g−1 lw和567 ng·g−1 lw. 其中,城市和农村地区母乳中的SCCPs浓度均低于2007年和2011年采集的母乳样品的分析结果,而MCCPs含量较2007年和2011年的结果迅速增长[87-88, 90]. 在所有的城乡样本中,河南省母乳样品中的SCCPs浓度最高(城市808 ng·g−1 lw,农村1543 ng·g−1 lw),因为河南省是中国最大的 CPs产地之一[90]. 内蒙古城市母乳样本(1714 ng·g−1 lw)和贵州省农村母乳样本(1089 ng·g−1 lw)中的 MCCPs浓度分别最高[90]. 在Xia等[87]2017年的研究中,由于农村地区没有工业活动,几乎所有城市地区母乳中的CPs 浓度都高于农村地区. 而Xu等[90]的研究结果表明,城市母乳样本与农村母乳样本中CPs浓度的比率范围为 0.3—2.2,食品包装和农业中广泛使用的地膜和保鲜膜会导致农村居民较高的CPs暴露水平. Xu等[90]的研究还表明,城市和农村母乳样本中 MCCPs/SCCPs 的比率分别为 1.6 ± 1.1和1.4 ± 1.1,因此应该增加对母乳中MCCPs的关注.

-

由于SCCPs可能通过血液循环进入多个器官,因此血清常被作为人类内部暴露于SCCPs的指标[91]. 已经有研究指出,血清中的SCCPs和MCCPs与男性肾功能有关[92]. 但由于样品制备和定量分析的困难[93],关于人体血液、血浆和血清中CPs污染的信息较少. 对于LCCPs,只有深圳市区人体血液的数据(1.0—21 ng·g−1 ww)[94]. 济南市50—84岁居民血清中SCCPs的浓度为107 ng·g−1 ww [95],与深圳市区人口血液中SCCPs 的浓度相当(98 ng·g−1 ww)[94],高于Zhao等[92]在济南市的研究(86.5 ng·g−1 ww)和大连市居民血浆中SCCPs的浓度(32.0 ng·g−1 ww)[93],低于Liu等[96]在济南市的研究(162 ng·g−1 ww). 而济南市50—84岁居民血清中MCCPs的浓度为134 ng·g−1 ww [95],与Liu等[96]的结果相当(142 ng·g−1 ww),高于深圳市区人口血液中MCCPs 的浓度(21 ng·g−1 ww)[94]和Zhao等[92]在济南市的研究(81.2 ng·g−1 ww). Ding等[95]分析影响居民血清样本中CPs浓度的因素可能有当地CPs的使用和排放量、研究人群的年龄、社会经济地位和饮食习惯等. 广州市人体血清中SCCPs和MCCPs的浓度范围分别是1.00—5.45 ng·mL−1和<MDL—2.74 ng·mL−1[97]. Chen等[98]研究了母亲全血中SCCPs和MCCPs的浓度,浓度范围分别为2.60—8.24 ng·mL−1和1.26—4.20 ng·mL−1. 目前,除中国外,其他国家的人类血清中的CPs数据都非常有限[22],只有澳大利亚、捷克和挪威有相应的报道. 澳大利亚男性血清中SCCPs和MCCPs的脂质重量分别为<DL—360 ng·g−1 lw和<DL—930 ng·g−1 lw,LCCPs的脂质重量为<MDL ng·g−1 lw [99]. 捷克成人血清中SCCPs和MCCPs的浓度范围分别为<150—2600 ng·g−1 lw和<200—2110 ng·g−1 lw [22]. 两国的数据都低于中国已有的数据(广州市血清的研究除外)[97]. Xu等[100]的研究结果表明,挪威女性血清合并样本中CPs的浓度范围为0.03—0.26 μg·L−1 ww. 其中,MCCPs的浓度随着时间的推移而增加,并且所有样本的平均 ΣMCCPs/ΣSCCPs 水平比为1.60,该研究强调了应对人体暴露于MCCPs的特别关注[100].

值得注意的是,已经有研究在脐带血清中发现SCCPs和MCCPs,说明CPs可以通过胎盘转移,给胎儿造成产前暴露的风险[101]. 北京市母亲血清中SCCPs和MCCPs的浓度范围分别为21.7—373 ng·g−1 ww和3.76—31.8 ng·g−1 ww,脐带血清中分别为8.51—107 ng·g−1 ww和1.33—12.9 ng·g−1 ww [101]. 四川省绵阳市母体血清、脐带血清中SCCPs中位浓度分别为117.1 ng·mL−1和70.0 ng·mL−1,MCCPs分别为38.9 ng·mL−1和25.6 ng·mL-1 [89],与武汉市母体血清、脐带血清中SCCPs(中位浓度分别为66.2 ng·mL−1和36.7 ng·mL−1)和MCCPs(中位浓度分别为126 ng·mL−1和34.2 ng·mL−1)浓度大致相同[102]. 在这些研究中,母体血液样本中发现的基于湿重的SCCPs和MCCPs浓度大约是脐带血样本中的2—5倍[103]. 中国南方母亲血浆中SCCPs和MCCPs的浓度范围分别为3.28—10.4 ng·mL−1和1.30—5.50 ng·mL−1,脐带血浆中SCCPs和MCCPs的浓度范围分别为0.89—4.13 ng·mL−1和0.89—1.69 ng·mL−1,都远低于北京市的结果[98]. 可能由于母体暴露的区域特异性而导致胎儿的暴露水平存在区域差异[98]. 母体血清和脐带血清的浓度差异表明胎盘在CPs从母体到胎儿的运输中起着重要作用[89]. 然而,目前产前通过胎盘转移暴露于CPs的研究较少,还需要进行更深入的研究.

-

Chen等[98]在32组血浆和胎盘样本中均检测到SCCPs和MCCPs,表明人类广泛暴露于CPs. CPs是一类有毒化学品,可能会通过胎盘从母亲体内向胎儿转移,对胎儿产生不良影响[21, 103]. Zhang等[103]对中国CPs经胎盘转移的研究进行了归纳和总结. 中国南方胎盘中SCCPs和MCCPs的浓度分别是3.18—9.12 ng·g−1 ww和1.91—4.89 ng·g−1 ww,高于对应的母体和脐带血液,说明CPs在胎盘中具有较高的保留或积累潜力[98]. 武汉市胎盘中SCCPs和MCCPs的浓度范围分别为10.2—132 ng·g−1 和24.8—642 ng·g-1[102]. 河南省胎盘样品中SCCPs和MCCPs的浓度范围分别为98.5—3771 ng·g−1 lw和80.8—954 ng·g−1 lw[21]. 绵阳市胎盘中SCCPs和MCCPs的中位浓度分别为30.3 ng·g−1 ww和19.0 ng·g−1 ww [89]. 除了胎盘之外,Han等[104]以头发和指甲作为人体CPs暴露的生物指标,报道了人体头发和指甲中的CPs浓度,并指出人的年龄可能是头发和指甲中CPs积累的主要影响因素. 中国北方人发中SCCPs和MCCPs的浓度范围分别为19.2—877 ng·g−1 dw和16.9—893 ng·g−1 dw,指甲中SCCPs和MCCPs的浓度范围分别为57.7—355 ng·g−1 dw和61.0—476 ng·g−1 dw[104].

-

本研究回顾了人体CPs外部暴露的3个主要途径,即饮食摄入、呼吸吸入和灰尘摄入. 室内空气暴露高于室外空气暴露. 饮食摄入是普通人群暴露于CPs的主要途径,多数研究中的饮食暴露量评估表明CPs不构成人体健康风险. 因为儿童体重较低,儿童的CPs暴露风险高于成年人. 本文还整理了有关CPs人体内部暴露的研究. 有多篇文献报道了我国的人群暴露,我国母乳和血清中SCCPs和MCCPs的含量高于国外. 针对目前CPs人体暴露的研究现状,本文提出以下3点展望:(1)加强MCCPs和LCCPs的人体暴露研究. 作为SCCPs的替代品,MCCPs和LCCPs的使用正在逐渐增加,我国MCCPs暴露呈现上升的趋势,有关其人体暴露风险评估的信息有限或完全缺乏;(2)提高CPs人体暴露研究的系统性. 针对饮食摄入、呼吸吸入、灰尘摄入和皮肤吸收这4种外暴露途径,明确各种途径对CPs外暴露的贡献率;(3)增加对人体蓄积代谢规律的研究. 开展CPs在生物体内的代谢研究,以明确CPs的代谢途径和产物,为科学评估CPs的暴露风险提供依据.

氯化石蜡的人体暴露研究进展

A review on human exposure to chlorinated paraffins

-

摘要: 短链氯化石蜡具有持久性有机污染物的特性,是列入《关于持久性有机污染物的斯德哥尔摩公约》全球管控的有机物,氯化石蜡在人体内蓄积,造成健康风险. 为研究氯化石蜡的人体暴露情况,对近20年来的相关论文进行综述. 氯化石蜡的人体暴露途径可以大致分为外部暴露途径和内部暴露途径. 外部暴露主要来自食物(饮食摄入)、空气(呼吸吸入)和室内灰尘(灰尘摄入和皮肤吸入). 对于内部暴露,目前在人体血液(血浆或血清)、母乳、胎盘、头发和指甲中均已检测到氯化石蜡. 与普通成年人群相比,儿童以及婴幼儿外部暴露氯化石蜡的风险较高. 中国由于较大的生产和使用量,人群暴露量相对较高. 目前需加强氯化石蜡分析方法的可比性,以及氯化石蜡在人体的蓄积代谢研究等. 同时,血液(血清或血浆)和母乳以外的其他生物指标中链和长链氯化石蜡人体暴露风险评估的研究也应得到重视.Abstract: Short-chain chlorinated paraffins, as a persistent organic pollutant, is listed in annex A under the Stockholm Convention. Chlorinated paraffins are bioaccumulative and toxic chemicals which can accumulate in human bodies and cause health risks. In order to investigate the human exposure to chlorinated paraffins, the related literatures in the recent 20 years were reviewed. Human exposure is generally divided into external exposure and internal exposure pathways. External exposure mainly including food (dietary intake), air (respiratory inhalation), and indoor dust (dust intake and dermal absorption) was documented. For internal exposure, chlorinated paraffins have been found in human blood (plasma or serum), breast milk, placenta, human hair, and nails. The results showed that children and infants have higher chlorinated paraffins risks of external exposure compared with the general adults. The Chinese people have higher exposure due to the large production and usage in China. Until now, there are few studies focusing on the accumulation and metabolism mechanism of chlorinated paraffins in the human body. New studies including chlorinated paraffins toxicity and kinetics, are highly requested. And the accurate quantitative analysis of chlorinated paraffins is rather difficult. Improving the comparability of chlorinated paraffins analysis methods is needed. At the same time, more studies focus on chlorinated paraffins in biomarkers beyond blood (serum or plasma) and breast milk should also raise concern.

-

Key words:

- chlorinated paraffins (CPs) /

- human exposure /

- food /

- air.

-

-

表 1 人体总膳食的CPs暴露情况

Table 1. Human dietary exposure to CPs

国家或地区

Country or region采样时间

Sampling time估计每日摄入量/ (ng·kg−1·d−1 bw)

Estimated daily intake(EDI)检测方法

Analytical method参考文献

ReferenceSCCPs 德国 2018.9—2019.8 100—420(成人) GC-ECNI-Orbitrap-HRMS [42] 410—1600(幼儿) 500—2000(婴儿) 瑞典 2015 18 APCI-HRMS [43] 日本 1990s 53 HRGC-ECNI-HRMS [39] 2003夏 110(成人) HRGC-ECNI-HRMS [40] 2009 54 HRGC-ECNI-HRMS [39] 韩国,首尔 1994 ND. HRGC-ECNI-HRMS [39] 2007 ND.—50 韩国 2016—2019 888(成年男性) GC-ECNI-MS [41] 781(成年女性) 中国,华南九省 2017—2018 700 GC×GC-ECNI-TOFMS [33] 中国,河北省 2016 1138.5—3795.8 GC-NCI-MS [47] 中国,北京 1993 ND.—36 HRGC-ECNI-HRMS [39] 2009 620 2016 316—1101 GC-TOF-HRMS [29] 2016 2350.5 GC-NCI-MS [47] 中国,呼伦贝尔 2016 2952.6 GC-NCI-MS [47] 中国,济南 2019.4 3109 GC-ECNI-MS [35] 2020.6—2020.9 1987.1 APCI-QTOF-MS [48] 2020 4128.3 APCI-QTOFMS [65] MCCPs 德国 2018.9—2019.8 100—840(成人) GC-ECNI-Orbitrap-HRMS [42] 390—2600(幼儿) 480—2900(婴儿) 瑞典 2015 39 APCI-HRMS [43] 中国,华南九省 2017—2018 470 GC×GC-ECNI-TOFMS [33] 中国,北京 2016 153—1307 GC-TOF-HRMS [29] 中国,济南 2020.6—2020.9 949.5 APCI-QTOF-MS [48] 2020 3230.2 APCI-QTOFMS [65] LCCPs 瑞典 2015 2.0 APCI-HRMS [43] 中国,济南 2020.6—2020.9 287.9 APCI-QTOF-MS [48] 注:ND.,未检出. ND.,not detected. 表 2 人体吸入室内空气的CPs暴露情况

Table 2. Human inhalation exposure to CPs

国家或地区

Country or region采样时间

Sampling time估计每日摄入量/(ng·kg−1·d−1 bw)

Estimated daily intake(EDI)检测方法

Analytical method参考文献

ReferencevSCCPs 挪威,奥斯陆 2013.11—2014.4 0.073 UPLC-APCI-Orbitrap-HRMS [71] SCCPs 挪威 2012 26(母亲) GC-ECNI-HRMS [72] 39(儿童) 挪威,奥斯陆 2013.11—2014.4 1.6 UPLC-APCI-Orbitrap-HRMS [71] 中国,北京 2014.7—2014.9 20.6(成人) GC-TOFHRMS [29] 2014.12—2015.3 51.7(幼儿) MCCPs 挪威,奥斯陆 2013.11—2014.4 0.23 UPLC-APCI-Orbitrap-HRMS [71] 中国,北京 2014.7—2014.9 1.49(成人) GC-TOFHRMS [29] 2014.12—2015.3 3.49(幼儿) LCCPs 挪威,奥斯陆 2013.11—2014.4 0.0046 UPLC-APCI-Orbitrap-HRMS [71] ∑CPs 挪威,奥斯陆 2013.11—2014.4 2.0 UPLC-APCI-Orbitrap-HRMS [71] 表 3 人体经灰尘暴露CPs的情况

Table 3. Human exposure to CPs via dust

国家或地区

Country or region采样时间

Sampling time估计每日摄入量/(ng·kg−1·d−1 bw)

Estimated daily intake(EDI)检测方法

Analytical method参考文献

Reference饮食摄入Ingestion vSCCPs 挪威,奥斯陆 2013.11—2014.4 0.00069 UPLC-APCI-Orbitrap-HRMS [71] SCCPs 挪威,奥斯陆 2013.11—2014.4 1.1 UPLC-APCI-Orbitrap-HRMS [71] 澳大利亚 2015.1—2015.3 0.46(成人) APCI-QTOF-HRMS [78] 42(儿童) 中国,北京 2014.7—2014.9 179(成人) GC-TOFHRMS [29] 2014.12—2015.3 1519(幼儿) 中国,大连 2015.4 20(成人) GC-ECNI-LRMS [79] 295(儿童) MCCPs 挪威,奥斯陆 2013.11—2014.4 0.70 UPLC-APCI-Orbitrap-HRMS [71] 澳大利亚 2015.1—2015.3 4.7(成人) APCI-QTOF-HRMS [78] 350(儿童) 中国,北京 2014.7—2014.9 93.3(成人) GC-TOFHRMS [29] 2014.12—2015.3 613(幼儿) 中国,大连 2015.4 17(成人) GC-ECNI-LRMS [79] 254(儿童) LCCPs 挪威,奥斯陆 2013.11—2014.4 0.09 UPLC-APCI-Orbitrap-HRMS [71] 澳大利亚 2015.1—2015.3 0.12(成人) APCI-QTOF-HRMS [78] 9.9(儿童) ∑CPs 挪威,奥斯陆 2013.11—2014.4 5.7 UPLC-APCI-Orbitrap-HRMS [71] 皮肤吸收Dermal uptake SCCPs 澳大利亚 2015.1—2015.3 6.9(成人) APCI-QTOF-HRMS [78] 22(儿童) 中国,大连 2015.4 191(成人) GC-ECNI-LRMS [79] 307(儿童) MCCPs 澳大利亚 2015.1—2015.3 66(成人) APCI-QTOF-HRMS [78] 190(儿童) 中国,大连 2015.4 165(成人) GC-ECNI-LRMS [79] 264(儿童) LCCPs 澳大利亚 2015.1—2015.3 1.8(成人) APCI-QTOF-HRMS [78] 5.3(儿童) -

[1] ENVIRONMENTCANADA C E P A. Priority substances list assessment report chlorinated paraffins [Z]. 1993 [2] ELJARRAT E, BARCELÓ D. Quantitative analysis of polychlorinated n-alkanes in environmental samples [J]. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2006, 25(4): 421-434. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2006.01.007 [3] SERRONE D M, BIRTLEY R D N, WEIGAND W, et al. Toxicology of chlorinated paraffins [J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 1987, 25(7): 553-562. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(87)90209-2 [4] CANTER N. Status of medium-and long-chain chlorinated paraffins [J]. Tribology & Lubrication Technology, 2016, 72(3): 34. [5] CHOO G, EKPE O D, PARK K W, et al. Temporal and spatial trends of chlorinated paraffins and organophosphate flame retardants in black-tailed gull (Larus crassirostris) eggs [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2022, 803: 150137. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150137 [6] HOUGHTON K L. Chlorinated paraffins [J]. Kirk‐Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, 2000, 6: 121-129. [7] GUIDA Y, CAPELLA R, KAJIWARA N, et al. Inventory approach for short-chain chlorinated paraffins for the Stockholm Convention implementation in Brazil [J]. Chemosphere, 2022, 287: 132344. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.132344 [8] CHEN C K, CHEN A N, LI L, et al. Distribution and emission estimation of short- and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins in Chinese products through detection-based mass balancing [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2021, 55(11): 7335-7343. [9] 郑结斌. 中国氯化石蜡行业现状及发展分析 [J]. 中国氯碱, 2021(1): 22-24. ZHENG J B. Current situation and development analysis of chlorinated paraffin industry in China [J]. China Chlor-Alkali, 2021(1): 22-24(in Chinese).

[10] WEI G L, LIANG X L, LI D Q, et al. Occurrence, fate and ecological risk of chlorinated paraffins in Asia: A review [J]. Environment International, 2016, 92-93: 373-387. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.04.002 [11] MA X D, ZHANG H J, ZHOU H Q, et al. Occurrence and gas/particle partitioning of short- and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins in the atmosphere of Fildes Peninsula of Antarctica [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2014, 90: 10-15. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.03.021 [12] RUBIROLA A, SANTOS F J, BOLEDA M R, et al. Routine method for the analysis of short-chain chlorinated paraffins in surface water and wastewater [J]. CLEAN - Soil, Air, Water, 2018, 46(2): 1600151. doi: 10.1002/clen.201600151 [13] WU Y, GAO S T, JI B J, et al. Occurrence of short- and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins in soils and sediments from Dongguan City, South China [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2020, 265: 114181. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114181 [14] 陈满英, 路风辉, 陈纪文, 等. 珠江三角洲沉积柱中氯化石蜡的垂直变化规律 [J]. 环境化学, 2014, 33(5): 832-836. CHEN M Y, LU F H, CHEN J W, et al. Temporal distributions of chlorinated paraffins in sediments core from the Pearl River Delta [J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2014, 33(5): 832-836(in Chinese).

[15] IOZZA S, MÜLLER C E, SCHMID P, et al. Historical profiles of chlorinated paraffins and polychlorinated biphenyls in a dated sediment core from Lake Thun (Switzerland) [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2008, 42(4): 1045-1050. [16] JIANG L, GAO W, MA X D, et al. Long-term investigation of the temporal trends and gas/particle partitioning of short- and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins in ambient air of King George Island, Antarctica [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2021, 55(1): 230-239. [17] DU X Y, YUAN B, ZHOU Y H, et al. Chlorinated paraffins in two snake species from the Yangtze River Delta: Tissue distribution and biomagnification [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2020, 54(5): 2753-2762. [18] COOLEY H M, FISK A T, WIENS S C, et al. Examination of the behavior and liver and thyroid histology of juvenile rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) exposed to high dietary concentrations of C10-, C11-, C12- and C14-polychlorinated n-alkanes [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2001, 54(1-2): 81-99. doi: 10.1016/S0166-445X(00)00172-7 [19] UNEP. Recommendation by the persistent organic pollutants review committee to list short-chain chlorinated paraffins in annex A to the convention and draft text of the proposed amendment [Z]. UNEP Nairobi, India. 2017 [20] YUAN B, VORKAMP K, ROOS A M, et al. Accumulation of short-, medium-, and long-chain chlorinated paraffins in marine and terrestrial animals from Scandinavia [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2019, 53(7): 3526-3537. [21] WANG Y, GAO W, WANG Y W, et al. Distribution and pattern profiles of chlorinated paraffins in human placenta of Henan Province, China [J]. Environmental Science and Technology Letters, 2018, 5: 9-13. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.7b00499 [22] TOMASKO J, STUPAK M, PARIZKOVA D, et al. Short- and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins in human blood serum of Czech population [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 797: 149126. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149126 [23] WYATT I, COUTSS C T, ELCOMBE C R. The effect of chlorinated paraffins on hepatic enzymes and thyroid hormones [J]. Toxicology, 1993, 77(1-2): 81-90. doi: 10.1016/0300-483X(93)90139-J [24] LIU L H, LI Y F, COELHAN M, et al. Relative developmental toxicity of short-chain chlorinated paraffins in Zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2016, 219: 1122-1130. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.09.016 [25] GENG N B, ZHANG H J, ZHANG B Q, et al. Effects of short-chain chlorinated paraffins exposure on the viability and metabolism of human hepatoma HepG2 cells [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2015, 49(5): 3076-3083. [26] WANG X, ZHU J B, KONG B D, et al. C9-13 chlorinated paraffins cause immunomodulatory effects in adult C57BL/6 mice [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 675: 110-121. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.04.199 [27] 任晓倩, 张海军, 耿柠波, 等. 短、中、长链氯化石蜡暴露对细胞代谢影响的比较研究 [J]. 生态毒理学报, 2019, 14(6): 77-85. REN X Q, ZHANG H J, GENG N B, et al. Comparing the disrupting effects of short-, medium-and long-chain chlorinated paraffins on human hepatic cell metabolism [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2019, 14(6): 77-85(in Chinese).

[28] BENDIG P, HÄGELE F, VETTER W. Widespread occurrence of polyhalogenated compounds in fat from kitchen hoods [J]. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 2013, 405(23): 7485-7496. doi: 10.1007/s00216-013-7194-5 [29] GAO W, CAO D D, WANG Y J, et al. External exposure to short- and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins for the general population in Beijing, China [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52(1): 32-39. [30] FRIDÉN U E, MCLACHLAN M S, BERGER U. Chlorinated paraffins in indoor air and dust: Concentrations, congener patterns, and human exposure [J]. Environment International, 2011, 37(7): 1169-1174. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2011.04.002 [31] DU X Y, ZHOU Y H, LI J, et al. Evaluating oral and inhalation bioaccessibility of indoor dust-borne short- and median-chain chlorinated paraffins using in vitro Tenax-assisted physiologically based method [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2021, 402: 123449. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123449 [32] CHEN H, LAM J C W, ZHU M S, et al. Combined effects of dust and dietary exposure of occupational workers and local residents to short- and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins in a mega E-waste recycling industrial park in South China [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52(20): 11510-11519. [33] CUI L L, GAO L R, ZHENG M H, et al. Short- and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins in foods from the sixth Chinese total diet study: Occurrences and estimates of dietary intakes in South China [J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2020, 68(34): 9043-9051. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c03491 [34] WANG R H, GAO L R, ZHENG M H, et al. Short- and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins in aquatic foods from 18 Chinese provinces: Occurrence, spatial distributions, and risk assessment [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 615: 1199-1206. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.327 [35] LI H J, GAO S, YANG M L, et al. Dietary exposure and risk assessment of short-chain chlorinated paraffins in supermarket fresh products in Jinan, China [J]. Chemosphere, 2020, 244: 125393. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125393 [36] HUANG H T, GAO L R, ZHENG M H, et al. Dietary exposure to short- and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins in meat and meat products from 20 provinces of China [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2018, 233: 439-445. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.10.022 [37] SHI Z X, ZHANG L, LI J G, et al. Novel brominated flame retardants in food composites and human milk from the Chinese Total Diet Study in 2011: Concentrations and a dietary exposure assessment [J]. Environment International, 2016, 96: 82-90. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.09.005 [38] FAN X R, WANG Z W, LI Y, et al. Estimating the dietary exposure and risk of persistent organic pollutants in China: A national analysis [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 288: 117764. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117764 [39] HARADA K H, TAKASUGA T, HITOMI T, et al. Dietary exposure to short-chain chlorinated paraffins has increased in Beijing, China [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2011, 45(16): 7019-7027. [40] IINO F, TAKASUGA T, SENTHILKUMAR K, et al. Risk assessment of short-chain chlorinated paraffins in Japan based on the first market basket study and species sensitivity distributions [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2005, 39(3): 859-866. [41] LEE S M, CHOO G, EKPE O D, et al. Short-chain chlorinated paraffins in various foods from Republic of Korea: Levels, congener patterns, and human dietary exposure [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2020, 263: 114520. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114520 [42] KRÄTSCHMER K, SCHÄCHTELE A, VETTER W. Short- and medium-chain chlorinated paraffin exposure in South Germany: A total diet, meal and market basket study [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 272: 116019. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.116019 [43] DARNERUD P, BECKER W, OHRVIK V, et al. Swedish Market Basket Survey 2015: Per capita-based analysis of nutrients and toxic compounds in market baskets and assessment of benefit or risk [R]. Livsmedelsverkets Rapportserie; National Food Agency: Uppsala, Sweden, 2017. [44] WANG R H, GAO L R, ZHENG M H, et al. Characterization of short- and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins in cereals and legumes from 19 Chinese provinces [J]. Chemosphere, 2019, 226: 282-289. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.03.148 [45] IPCS. Environmental Health Criteria 181: Chlorinated Paraffins. [EB/OL]. Geneva: WHO, 1996 [2022-8-5]. [46] WEBER R. Learning from Dioxin & PCBs in meat – problems ahead? [J]. IOP Conference Series:Earth and Environmental Science, 2017, 85: 012002. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/85/1/012002 [47] 陈慧玲, 申金山, 王雪光, 等. 膳食中短链氯化石蜡的污染状况及风险暴露评估 [J]. 食品科学, 2019, 40(21): 143-149. CHEN H L, SHEN J S, WANG X G, et al. Dietary pollution status and exposure risk assessment of short-chain chlorinated paraffins [J]. Food Science, 2019, 40(21): 143-149(in Chinese).

[48] DING L, ZHANG S W, ZHU Y T, et al. Overlooked long-chain chlorinated paraffin (LCCP) contamination in foodstuff from China [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 801: 149775. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149775 [49] HAN X, CHEN H, DENG M, et al. Chlorinated paraffins in infant foods from the Chinese market and estimated dietary intake by infants [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2021, 411: 125073. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.125073 [50] KRÄTSCHMER K, SCHÄCHTELE A, VETTER W. Chlorinated paraffins in baby food from the German market [J]. Food Control, 2021, 123: 107689. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107689 [51] CAO Y, HARADA K H, LIU W Y, et al. Short-chain chlorinated paraffins in cooking oil and related products from China [J]. Chemosphere, 2015, 138: 104-111. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.05.063 [52] GAO W, BAI L, KE R H, et al. Distributions and congener group profiles of short-chain and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins in cooking oils in Chinese markets [J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2020, 68(29): 7601-7608. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c02328 [53] WANG Y J, WU X Y, WANG Y X, et al. Short- and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins in green tea from 11 Chinese provinces and their migration from packaging [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2022, 427: 128192. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.128192 [54] DONG S J, ZHANG S, LI X M, et al. Occurrence of short- and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins in raw dairy cow milk from five Chinese provinces [J]. Environment International, 2020, 136: 105466. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105466 [55] WANG S, GAO L R, ZHENG M H, et al. Occurrences, congener group profiles, and risk assessment of short- and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins in cup instant noodles from China [J]. Chemosphere, 2021, 279: 130503. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130503 [56] HUANG Y M, QING X, JIANG G, et al. Short-chain chlorinated paraffins in fish from two developed regions of China: Occurrence, influencing factors and implication for human exposure via consumption [J]. Chemosphere, 2019, 236: 124317. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.07.048 [57] KRÄTSCHMER K, SCHÄCHTELE A, MALISCH R, et al. Chlorinated paraffins (CPs) in salmon sold in southern Germany: Concentrations, homologue patterns and relation to other persistent organic pollutants [J]. Chemosphere, 2019, 227: 630-637. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.04.016 [58] ZHANG K, SCHNOOR J L, ZENG E Y. E-waste recycling: Where does it go from here? [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2012, 46(20): 10861-10867. [59] van MOURIK L M, GAUS C, LEONARDS P E G, et al. Chlorinated paraffins in the environment: A review on their production, fate, levels and trends between 2010 and 2015 [J]. Chemosphere, 2016, 155: 415-428. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.04.037 [60] ZENG Y H, HUANG C C, LUO X J, et al. Polychlorinated biphenyls and chlorinated paraffins in home-produced eggs from an e-waste polluted area in South China: Occurrence and human dietary exposure [J]. Environment International, 2018, 116: 52-59. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.04.006 [61] YUAN B, FU J J, WANG Y W, et al. Short-chain chlorinated paraffins in soil, paddy seeds (Oryza sativa) and snails (Ampullariidae) in an e-waste dismantling area in China: Homologue group pattern, spatial distribution and risk assessment [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2017, 220: 608-615. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.10.009 [62] ZENG Y H, LUO X J, TANG B, et al. Habitat- and species-dependent accumulation of organohalogen pollutants in home-produced eggs from an electronic waste recycling site in South China: Levels, profiles, and human dietary exposure [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2016, 216: 64-70. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.05.039 [63] CANADA E. Chlorinated Paraffins. Follow-up Report on a PSL1 Assessment for Which Data Were Insufficient to Conclude whether the Substances Were “toxic” to the Environment and to the Human Health [Z]. Canadian Environmental Protection Agency Ottawa, Canada. 2008 [64] CUI L L, GAO L R, ZHENG M H, et al. Bioaccessibility of short chain chlorinated paraffins in meat and seafood [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 668: 996-1003. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.043 [65] 方昕鑫, 张仕文, 朱雨婷, 等. 济南市食品中短、中链氯化石蜡的污染特征及摄入风险评估 [J]. 山东大学学报(工学版), 2021, 51(3): 119-128. FANG X X, ZHANG S W, ZHU Y T, et al. Pollution characteristics and intake risk assessment of short and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins in foods in Jinan [J]. Journal of Shandong University (Engineering Science), 2021, 51(3): 119-128(in Chinese).

[66] LIU X T, ZHIGUO C, GANG Y. Human exposure to emerging halogenated flame retardants [J]. Comprehensive Analytical Chemistry, 2020, 88: 215-251. [67] HUANG H T, GAO L R, XIA D, et al. Characterization of short- and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins in outdoor/indoor PM10/PM2.5/PM1. 0 in Beijing, China [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2017, 225: 674-680. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.03.054 [68] GAO W, WU J, WANG Y W, et al. Distribution and congener profiles of short-chain chlorinated paraffins in indoor/outdoor glass window surface films and their film-air partitioning in Beijing, China [J]. Chemosphere, 2016, 144: 1327-1333. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.09.075 [69] LU H, ZHU L Z, CHEN S G. Pollution level, phase distribution and health risk of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in indoor air at public places of Hangzhou, China [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2008, 152(3): 569-575. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2007.07.005 [70] AL SAIFY I, CIONI L, van MOURIK L M, et al. Optimization of a low flow sampler for improved assessment of gas and particle bound exposure to chlorinated paraffins [J]. Chemosphere, 2021, 275: 130066. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130066 [71] YUAN B, TAY J H, PADILLA-SÁNCHEZ J A, et al. Human exposure to chlorinated paraffins via inhalation and dust ingestion in a Norwegian cohort [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2021, 55(2): 1145-1154. [72] SAKHI A K, CEQUIER E, BECHER R, et al. Concentrations of selected chemicals in indoor air from Norwegian homes and schools [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 674: 1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.04.086 [73] ZHUO M H, MA S T, LI G Y, et al. Chlorinated paraffins in the indoor and outdoor atmospheric particles from the Pearl River Delta: Characteristics, sources, and human exposure risks [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 650: 1041-1049. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.107 [74] LIU D, LI Q L, CHENG Z N, et al. Spatiotemporal variations of chlorinated paraffins in PM2.5 from Chinese cities: Implication of the shifting and upgrading of its industries [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2020, 259: 113853. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113853 [75] ZHOU W, SHEN M J, LAM J C W, et al. Size-dependent distribution and inhalation exposure characteristics of particle-bound chlorinated paraffins in indoor air in Guangzhou, China [J]. Environment International, 2018, 121: 675-682. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.10.004 [76] LI H J, LI J K, LI H Z, et al. Seasonal variations and inhalation risk assessment of short-chain chlorinated paraffins in PM2.5 of Jinan, China [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2019, 245: 325-330. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.10.133 [77] LI Q L, GUO M R, SONG H, et al. Size distribution and inhalation exposure of airborne particle-bound polybrominated diphenyl ethers, new brominated flame retardants, organophosphate esters, and chlorinated paraffins at urban open consumption place [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 794: 148695. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148695 [78] HE C, BRANDSMA S H, JIANG H, et al. Chlorinated paraffins in indoor dust from Australia: Levels, congener patterns and preliminary assessment of human exposure [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 682: 318-323. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.170 [79] SHI L M, GAO Y, ZHANG H J, et al. Concentrations of short- and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins in indoor dusts from malls in China: Implications for human exposure [J]. Chemosphere, 2017, 172: 103-110. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.12.150 [80] LIU L H, MA W L, LIU L Y, et al. Occurrence, sources and human exposure assessment of SCCPs in indoor dust of northeast China [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2017, 225: 232-243. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.03.008 [81] KRÄTSCHMER K, MALISCH R, VETTER W. Chlorinated paraffin levels in relation to other persistent organic pollutants found in pooled human milk samples from primiparous mothers in 53 countries [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2021, 129(8): 87004. doi: 10.1289/EHP7696 [82] SURENJAV E, LKHASUREN J, FIEDLER H. POPs monitoring in Mongolia - core matrices [J]. Chemosphere, 2022, 297: 134180. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.134180 [83] TOMY G T, FISK A T, WESTMORE J B, et al. Environmental chemistry and toxicology of polychlorinated n-alkanes [J]. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 1998, 158: 53-128. [84] THOMAS G O, FARRAR D, BRAEKEVELT E, et al. Short and medium chain length chlorinated paraffins in UK human milk fat [J]. Environment International, 2006, 32(1): 34-40. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2005.04.006 [85] ZHOU Y H, YUAN B, NYBERG E, et al. Chlorinated paraffins in human milk from urban sites in China, Sweden, and Norway [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2020, 54(7): 4356-4366. [86] HU L Q, LUO D, WANG L M, et al. Levels and profiles of persistent organic pollutants in breast milk in China and their potential health risks to breastfed infants: A review [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 753: 142028. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142028 [87] XIA D, GAO L R, ZHENG M H, et al. Health risks posed to infants in rural China by exposure to short- and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins in breast milk [J]. Environment International, 2017, 103: 1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.03.013 [88] XIA D, GAO L R, ZHENG M H, et al. Human exposure to short- and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins via mothers' milk in Chinese urban population [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2017, 51(1): 608-615. [89] LIU Y X, AAMIR M, LI M Y, et al. Prenatal and postnatal exposure risk assessment of chlorinated paraffins in mothers and neonates: Occurrence, congener profile, and transfer behavior [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2020, 395: 122660. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122660 [90] XU C, WANG K R, GAO L R, et al. Highly elevated levels, infant dietary exposure and health risks of medium-chain chlorinated paraffins in breast milk from China: Comparison with short-chain chlorinated paraffins [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 279: 116922. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116922 [91] HE H Z, LI Y Y, SHEN R, et al. Environmental occurrence and remediation of emerging organohalides: A review [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 290: 118060. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.118060 [92] ZHAO N, FANG X X, ZHANG S W, et al. Male renal functions are associated with serum short- and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins in residents from Jinan, China [J]. Environment International, 2021, 153: 106514. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106514 [93] XU J Z, GUO W J, WEI L H, et al. Validation of a HRGC-ECNI/LRMS method to monitor short-chain chlorinated paraffins in human plasma [J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2019, 75: 289-295. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2018.04.004 [94] LI T, WAN Y, GAO S X, et al. High-throughput determination and characterization of short-, medium-, and long-chain chlorinated paraffins in human blood [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2017, 51(6): 3346-3354. [95] DING L, LUO N N, LIU Y, et al. Short and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins in serum from residents aged from 50 to 84 in Jinan, China: Occurrence, composition and association with hematologic parameters [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 728: 137998. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137998 [96] LIU Y, HAN X M, ZHAO N, et al. The association of liver function biomarkers with internal exposure of short- and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins in residents from Jinan, China [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 268: 115762. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115762 [97] ZHOU X, WU H Q, HUANG X L, et al. Development a simple and rapid HPLC-ESI-Q-TOF/MS method for determination of short- and medium- chain chlorinated paraffins in human serum [J]. Journal of Chromatography B, 2019, 1126-1127: 121722. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2019.121722 [98] CHEN H, ZHOU W, LAM J C W, et al. Blood partitioning and whole-blood-based maternal transfer assessment of chlorinated paraffins in mother-infant pairs from South China [J]. Environment International, 2020, 142: 105871. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105871 [99] van MOURIK L M, TOMS L M L, HE C, et al. Evaluating age and temporal trends of chlorinated paraffins in pooled serum collected from males in Australia between 2004 and 2015 [J]. Chemosphere, 2020, 244: 125574. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125574 [100] XU S S, HANSEN S, RAUTIO A, et al. Monitoring temporal trends of dioxins, organochlorine pesticides and chlorinated paraffins in pooled serum samples collected from Northern Norwegian women: The MISA cohort study [J]. Environmental Research, 2022, 204: 111980. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111980 [101] QIAO L, GAO L R, ZHENG M H, et al. Mass fractions, congener group patterns, and placental transfer of short- and medium-chain chlorinated paraffins in paired maternal and cord serum [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52(17): 10097-10103. [102] AAMIR M, YIN S S, GUO F J, et al. Congener-specific mother-fetus distribution, placental retention, and transport of C10-13 and C14-17 chlorinated paraffins in pregnant women [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2019, 53(19): 11458-11466. [103] ZHANG X L, CHENG X M, LEI B L, et al. A review of the transplacental transfer of persistent halogenated organic pollutants: Transfer characteristics, influential factors, and mechanisms [J]. Environment International, 2021, 146: 106224. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106224 [104] HAN X, CHEN H, SHEN M J, et al. Hair and nails as noninvasive bioindicators of human exposure to chlorinated paraffins: Contamination patterns and potential influencing factors [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 798: 149257. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149257 -

下载:

下载: