-

全氟和多氟烷基物质(per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances,PFASs)是一类具有环境持久性和生物毒性的有机化合物,普遍存在于环境及生物介质中. PFASs具有防水、拒油、防污等功能,故因此被广泛应用于各类日常生活用品中,例如家用地毯、家具、生活办公用纸、电子电器产品、聚四氟乙烯产品和消防泡沫等[1 − 2]. PFASs这类化合物具有很强的稳定性,是由于PFASs碳原子上的氢原子全部或者多数被氟原子所取代,所以难以被光解、水解和微生物降解. 根据PFASs碳链所链接的官能团的不同,可分为离子化全氟和多氟烷基化合物(perfluoroalkyl acids, PFAAs)和中性全氟和多氟烷基化合物(neutral PFASs). 其中,PFAAs中由于其带电基团不同,又可分为全氟羧酸类化合物(perfluorocarboxylic acid, PFCAs)和全氟磺酸类化合物(perfluorosulfonic acid, PFSAs).

在全球范围内,PFASs在水体、土壤、大气和灰尘等环境介质[3]以及人体生物样本[4]和食物[5]中均有不同程度的检出. 有动物实验研究表明,部分PFASs具有生殖毒性、神经毒性和免疫毒性[6]. 且一般情况下,长链PFASs(八碳及以上链长)较短链(八碳以下)PFASs毒性更强[7],且易于在生物体内富集[8]. 因此从目前来看,短链PFASs被认为是更为环保和健康的长链PFASs替代品,并且短链PFASs正逐步替代长链PFASs在各类产品中的使用. 对于处于食物链最顶端的人类来说,PFASs的生物富集能力及毒性使越来越多的研究人员开始关注其对人体产生的健康风险. 2009年,全氟辛烷磺酸(perfluorooctane hyphensulfonic acid,PFOS)及其盐类和全氟辛烷磺酰氟(perfluorooctane sulfonyl fluoride,PFOSF)作为新增的持久性有机污染物(POPs),被联合国环境规划署列入持久性有机污染物名单. 此外,在联合国环境规划署分别召开举办的2015年和2017年的第七次和第十三次POPs大会上,全氟辛烷羧酸(perfluorooctanoic acid,PFOA)和全氟己烷磺酸(perfluorohexane sulfonic acid,PFHxS)也被提议列入斯德哥尔摩公约的POPs名单[9]. 在2022年, 我国对生活饮用水中的部分PFASs进行了限制, 其中PFOA和PFOS的浓度限值分别是80 ng·L−1和40 ng·L−1.

人体生物监测可用于评估人群对环境化学品和有毒物质的暴露情况. 当前,许多国家已经建立了国家人体生物监测计划[10],包括美国(国家健康和营养检查调查;NHANES)、加拿大(加拿大健康措施调查)、德国(联邦环境局人体生物监测委员会)和法国(法国卫生部和环境部). 此外,欧洲联盟建立了由28个国家、欧洲环境署和欧洲委员会共同的合作欧洲人类生物监测项目. 对于人体生物样本中PFASs的检测分析,最常用的基质包括血液、尿液、母乳、头发和指甲等. 不同基质中PFASs的研究会有一定的区别,从取样方面来看,根据取样方式对人体是否产生损伤,可以分为创伤性采样和无损性采样. 不同的基质,其反应的暴露浓度也会存在一定的时效性. 血液中PFASs检测水平可以直接反映人体暴露后吸收的PFASs的含量,但是由于血液检测是创伤性采样,较难取得采样对象的配合及采样合法性,在一定程度上限制了这种人体生物样本的应用. 尿液是PFASs检测使用最为广泛的人体生物样本,不仅较易获得,而且可大体积采样,易于检测. 头发对环境中的PFASs具有蓄积作用,因此,检测头发中PFASs的含量可以反映人体较长时间的污染物暴露情况. 一般情况下,头发可用于反映约一个月的既往暴露情况.

人体生物样本中PFASs的检测对了解PFASs的污染状况及其对人体健康的影响具有重要的意义. 本文总结了人体样品中PFASs的检测方法及含量水平,比较了不同前处理和仪器分析方法的优缺点,同时对全球范围内人体生物样本中PFASs的赋存情况进行了综述,并对存在的问题以及未来的发展趋势进行展望,以期为PFASs方法学研究、人体健康风险评价、污染监管与防控等提供参考依据. 主要PFASs名称信息见表1.

-

人体生物样本中PFASs的检测主要包括两部分:样品的前处理和仪器检测分析. 人体生物样本基质成分复杂,直接检测会产生背景干扰,必须通过特定的前处理方法,将待测物进行萃取、分离和浓缩,一方面可以减少基质成分对测定的干扰,另一方面可以使待测物转变成适合仪器检测的形式.

-

不同人体生物样品中PFASs的含量不尽相同,在检测分析前如何进行科学的前处理过程,以降低基质效应对检测结果的影响,使富集、浓缩、净化后的样品获得更优的检出限和回收率,是前处理方法研究的核心要素. 对于人体生物样本中PFASs的提取,常用的前处理方法有固相萃取、离子对萃取、碱消解、加速溶剂萃取、固相微萃取等. 各类前处理方法的优缺点见表2,不同前处理方法比较见表3.

-

固相萃取法(SPE法)是基于吸附原理,通过不同萃取剂的选择吸附性,使目标化合物吸附于萃取剂上,再进行洗脱的方法. 在多种基质中,SPE法是PFASs萃取过程中最常用的方法. 而在PFASs的萃取中使用较为广泛的SPE柱为弱阴离子交换柱(如WAX柱)、反相吸附柱(如HLB柱)等. 对于不同萃取柱的选择使用情况是根据所检测的目标化合物极性的不同所致,如离子型的全氟羧酸化合物(PFCAs)、全氟磺酸化合物(PFSAs)等根据其极性,可选择中等极性的WAX柱,而长链PFASs可以使用极性较小或非极性的HLB柱. 罗新月等[11]采用SPE法检测尿液中的PFASs,可同时测定尿液中12种PFASs,其方法在0.050—100 ng·mL−1范围内线性良好,且方法检出限(LOD)和定量限(LOQ)分别为0.032—6.50 ng·L−1和

0.00010 —0.021 ng·mL−1,12种PFASs的加标回收率为91.50%—114.00%,日内精密度和日间精密度分别为0.57%—16.00%和1.88%—20.10%.近年来,由于传统SPE技术存在自动化程度低、耗时长以及消耗样品和试剂量大等劣势,有研究者开发了在线SPE技术. 在线SPE技术具有自动化程度高、使用试剂量少、萃取速度快、引入污染小、样品量少等显著优点,因此被广泛用于少量珍贵样品中PFASs的检测. Pan等[12]开发了一种基于硅微流控芯片平台的微量分析方法,把固相萃取柱直接制作到芯片上,以压力为驱动力,由微阀和微泵控制液体的流动,可用于萃取小体积(小于5 µL)血液中的PFASs. 通过将固相萃取柱直接制作到芯片上,可提高萃取系统的集成度,减少前处理过程中样品损失及污染等问题. Gao等[13]建立了一种灵敏、可靠、全自动化的在线Turboflow SPE-UHPLC-MS/MS方法,可同时检测人血清中43种PFASs,具有良好的线性关系(R2>0.99)、方法检出限((0.013±0.089) ng·mL−1)、回收率(84.30%—109.00%)和相对标准偏差(RSD)(日内RSD:1.30%—12.60%,日间RSD:1.70%—13.80%,周间RSD:1.80% —13.50%,月间RSD:3.10%—12.40%),为实时监测PFASs前体在体内和体外的降解动力学提供了可行性.

-

离子对萃取法是基于其目标化合物和离子对试剂结合后形成离子缔合物,再选择适合的有机试剂进行萃取的方法. 对于人体生物样品中PFASs的离子对萃取技术,主要以四丁基硫酸氢铵(TBA)为离子对试剂,使目标物生成阳离子缔合物,再以甲基叔丁基醚(MTBE)进行萃取. 谢琳娜等[14]采用离子对液液萃取技术对血清样品进行前处理,后经超高效液相色谱-串联质谱法进行分析检测. 检测结果显示18种PFASs在0.01—5.00 ng·mL−1浓度范围内具有良好线性,相关系数(R2)均大于0.99,方法检出限在0.010 ng·mL−1至0.10 ng·mL−1之间,方法定量限在0.050 ng·mL−1至0.50 ng·mL−1之间,加标回收率在71.40%至119.80%之间,平行样品间相对标准偏差小于15.00%. Wu等[15]对上海市人群血清中17种全氟化合物进行了分析,其利用了离子对萃取法建立并验证了一种通过改进高效液相色谱-串联质谱仪来消除仪器中PFOA背景污染的方法. 其中PFOS和PFOA的检出限分别为2.23 ng·mL−1和1.60 ng·mL−1,其它15种PFASs的检出限为0.040—0.88 ng·mL−1,加标回收率在50%—130%左右.

-

PFASs具有亲蛋白质的特性,因此富含蛋白质的生物基质样品在萃取过程中易产生蛋白质与溶剂之间的竞争效应,从而导致萃取不完全的现象. 通过碱消解前处理方法,能对蛋白质结构造成破坏,完全释放与其结合的PFASs,提升萃取效率. 因此,该方法经常用于生物样品中PFASs的前处理,常用消解液为氢氧化钾(KOH)和氢氧化钠(NaOH)的甲醇或水溶液. So等[16]对比了不同浓度的KOH甲醇溶液和KOH水溶液的消解效果,发现KOH-甲醇溶液(0.010 mol·L−1)对9种PFASs的回收率均大于70%;而KOH-水溶液的萃取效率相对较差,尤其是对PFUdA和PFDoA的回收率仅在 2.10%至24.60%之间.

-

加速溶剂萃取法(ASE)是近些年发展起来的萃取技术,是指在高温和高压条件下,利用一定配比的有机溶剂作为萃取剂来对样品进行萃取的方法. 相对于其他萃取方法,ASE具有萃取速度快、回收率高、溶剂用量小等优势. 宋小飞等[17]利用加速溶剂萃取法结合液相色谱-质谱联用法分析检测血液样本中9种PFASs含量,方法的回收率为74.60% —128.80%,检出限为1.10 —25.10 ng·L−1. ASE主要是通过控制萃取反应过程中的条件, 如萃取试剂的配比组成、反应时间、反应温度等,用以提高萃取效率[18]. 这种萃取方式与其它方法的不同之处在于其能够实现高度自动化,且在单次运行中可以处理多个样品,并在反应过程中其化合物的形态不易发生变化.

-

固相微萃取(SPME)是一种环保、简单且快速的样品前处理技术,灵敏度高,可实现纳克级别的检测. 该技术依据吸附和脱附原理,用固相微萃取探针(又叫SPME探针)萃取富集在气、液或固体样品中的化合物,替代进样针进行气相色谱进样,此过程不使用有机溶剂和复杂设备. 采用固相微萃取可以同步完成萃取和富集,从而大大简化样品的前处理过程. 与传统的固相萃取相比,固相微萃取技术操作简单、空白值和分析时间大大降低. 固相微萃取可与气相色谱仪联用,可直接将萃取后的样品进行热解析,无需有机溶剂洗脱,是一种集萃取、富集融于一体,简化了样品前处理的步骤,减少了杂质的干扰. Mathurin等[19]建立了检测血液中PFASs的方法,经顶空固相微萃取(HS-SPME)提取和预富集后,用气相色谱-质谱仪(GC/MS)检测PFASs. Deng等[20]利用固相微萃取-表面涂覆木尖探针环境质谱仪联用快速分析复杂样品中的超痕量PFASs,在血液和母乳样品中的检测灵敏度提高了100—500倍. 该方法具有良好的线性关系,8个目标PFASs的相关系数R2不低于0.99,方法检出限为0.060—0.59 ng·L−1,方法定性限为0.21—1.98 ng·L−1.

-

对于人体生物样本的分析方法除了常见的前处理方法,还有一些特殊的针对特殊样本或者特定条件的处理方法. 顾奕等[21]利用毛细管电泳(CE)技术建立了全氟辛酸与人血清白蛋白(HSA)相互作用的分析方法,其对PFOA进行酰胺化衍生得到具有特征紫外吸收波长的产物CF3(CF2)6COHNCH2ph,其吸收波长为214 nm,可使用紫外吸收光谱法进行检测,并在人血清白蛋白与PFOA的相互作用机制研究中获得了应用. QuEChERS法是利用吸附剂与基质中的杂质相互作用,再通过超声离心等简单步骤来吸附杂质,从而达到除杂净化的目的. Wu等[22]开发了一种高效的QuEChERS方法,可用于同时测定尿液中9种PFCAs和5种PFSAs. 该方法对14种PFASs的方法检测限为0.020—1.28 ng·mL−1,回收率为82%—114%.

-

经萃取后的人体生物样本,需要根据待测物的性质和含量,选择合适的测定方法和仪器. 由于PFASs的特殊结构不具有紫外吸收和荧光性质,不能直接采用紫外检测器和荧光检测器进行检测. 人体生物样本中的PFASs含量通常处于痕量或超痕量水平,其常用的检测方法多是色谱与质谱联用的方法.

-

气相色谱-质谱法(GC-MS)是分析持久性有机污染物的经典方法,适用于分子量低、挥发性强的物质的分析. 对于全氟酰胺类化合物(perfluorooctanesulfonamides,PFOSAs)和全氟调聚醇类化合物(fluorotelomer alcohols,FTOHs)等挥发性较强的PFASs,可选用GC-MS技术进行检测. 而针对一些沸点高、饱和蒸气压低且较难挥发的PFSAs,则需先将其进行衍生化反应来生成酯类化合物才能采用GC-MS进行测定. Motas等[23]通过氯代甲酸烷基酯与PFASs反应生成衍生化的酯类化合物,用于分析西班牙母乳中全氟羧酸类化合物. Fujii等[24]采用溴甲苯溶液作为衍生剂,建立了母乳样品中6种化合物的GC-MS分析方法. 由于衍生化步骤过于繁琐及其反应影响因素较多,在反应过程中也可能引入外来污染物或者直接造成目标化合物损失,且衍生化试剂一般具有毒性、腐蚀性、易燃易爆等一些危害,这些原因也就限制了GC-MS技术在人体生物样本PFASs检测中的应用.

-

高效液相色谱-串联质谱法(HPLC-MS/MS)对PFASs具有较好的色谱分辨能力和较高的灵敏度,样品前处理工作简单、无需衍生化,同时可以根据目标物的性质选择不同的离子,是人体生物样本中PFASs检测最主要的技术手段. 随着液相色谱技术的发展,具有超高分离度、超高速度和超高灵敏度的超高液相色谱-串联质谱法(UPLC-MS/MS)也被应用于PFASs的检测[15,25]. 相较于高效液相色谱,超高效液相色谱柱效更高而柱长更短,缩短了样品检测时间. 肖永华等[26]建立了固相萃取结合UPLC-MS/MS技术检测人体血清中7种PFASs,目标化合物在1—5 µg·L−1范围内线性关系良好,检出限为0.10 µg·kg−1. 此外,随着未知PFASs的不断出现,基于高分辨质谱(HRMS)进行非靶向或可疑靶向筛选,是人体生物样本中PFASs检测方法学的研究热点之一.

-

应用于检测人体生物样本中PFASs暴露水平的生物基质主要包括侵入性基质血液,以及非侵入性基质尿液、母乳、头发和指甲等. 不同的人体生物样本能反映不同的PFASs内暴露时间,一般情况下,血液和尿液可反映近期人体暴露水平,头发和指甲反映过去一定时间段内的暴露水平,而母乳可以反映孕妇特定时期的PFASs内暴露水平.

-

血液是目前人体PFASs暴露研究的主要生物指示物之一. 研究表明,PFASs在全球不同国家和地区的血液样品中均有检出,其中PFOS和PFOA是检出率和含量较高的两种全氟烷基化合物[27]. 近年来,随着这两种全氟烷基化合物在各国市场上的逐步禁用与淘汰,其在人体血液中的检出含量及频率逐渐降低,但作为替代品的短链PFASs检出频率却在增加[28]. 由于采集血样属于损伤性采样,采样量少,因此需要建立相应的低检测限、高精度分析方法. 血液的前处理方法主要采用固相微萃取和离子对萃取方式,常用的固相萃取柱为WAX柱.

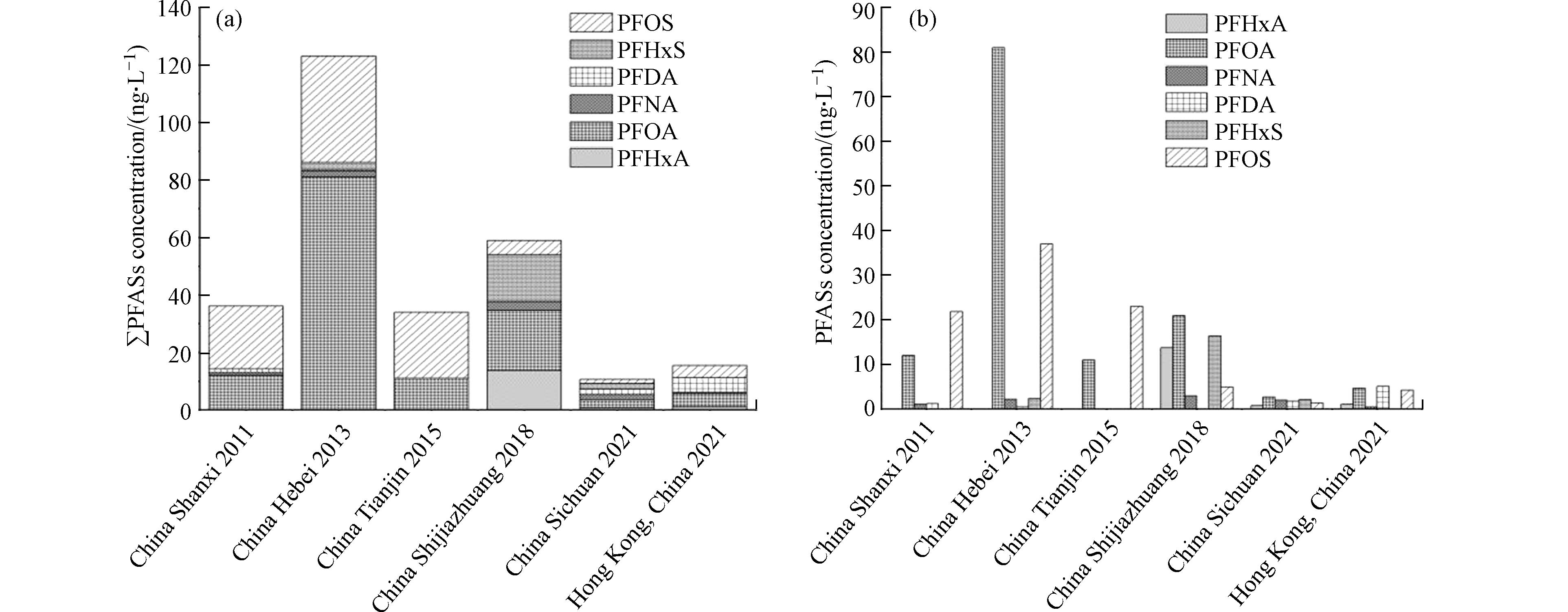

针对普通人群,Li等[29]检测了广东省、广西壮族自治区和海南省等华南三省的人群血清中8种PFASs的暴露情况,研究发现,∑8PFASs的浓度范围为0.85—24.30 ng·mL−1,其中PFOA和PFOS为主要污染物质,分别占8种PFASs总浓度的38.50%和42.80%;不同地区人群血清中PFASs的组成成分并没有显著性差异. Wu等[15]对上海市嘉定区45例23—87岁随机人群血清中17种PFASs进行了检测与分析,共有11种PFASs被检出,PFOS和PFOA为主要检出物质,其浓度分别占PFASs总浓度的49.50%和34.20%;血清中11种PFASs总浓度范围为<LOD—99.40 ng·mL−1,中位数为53.40 ng·mL−1. 有学者对我国居住少数民族人数较多的新疆维吾尔自治区人体血清样品中PFASs暴露水平进行了研究,通过PFOS和PFOA检测结果表明,在110个样品中仅有7个样品的PFOS和PFOA高于定量限,其浓度范围分别为5.00—44.70 ng·mL−1和1.50—10 ng·mL-1[30]. Guo等[31]对秦皇岛市、唐山市、威海市和邹平市等4个环渤海城市人群血液中的9种PFASs进行了研究,其中,唐山市人群血液中PFASs含量最高(14.010 ng·mL−1),邹平市最低(7.29 ng·mL−1). Liu等[27]和Liao等[28]分别对我国浙江(衢州)地区和广西地区人体血液样本进行了检测,其中PFOA和PFOS依旧是检出水平较高的物质,PFOA在两个地区的平均浓度分别为4.00 ng·mL−1和2.31 ng·mL−1,PFOS在两个地区的平均浓度分别为2.60 ng·mL−1和1.13 ng·mL−1. 在国外,2008—2013年丹麦孕妇血清中PFASs的浓度趋势表明,PFNA、PFDA、PFUdA随时间呈下降趋势,但PFOS依旧是最主要的PFASs[32]. 2002年至2013年澳大利亚的血清样品部分PFCAs和PFSAs亦呈现出下降趋势[33]. NHANES机构统计了2007—2010美国居民血清中PFASs的浓度变化情况,发现PFOA、PFOS和PFHxS也均有所下降[34]. 2017年,加拿大有学者开展了一项人体血液健康检测研究,其对血液中PFASs暴露水平进行了检测,检测结果显示男性PFOA和PFHxS浓度较高,而女性的PFDA和PFUnDA浓度较高[35]. 图1(a)总结了国内外普通人群血液中PFASs暴露水平,图1(b)比较了普通人群血液中6种主要PFASs的单暴露水平. 总体而言,上海市普通人群血液中PFOA和PFOS的浓度均处于较高水平,其他国家和地区普通人群血液中PFASs暴露水平处于相同的数量级.

针对职业暴露人群,Fu等[36]对湖北省某氟化工厂工人血液中PFASs的赋存状况进行了研究,其中检出水平较高的化合物为PFOS、PFHxS和PFOA,中位数浓度分别是

1725 ng·mL−1、764 ng·mL−1和427 ng·mL−1. 该研究同时将工人尿液和血液中PFASs的组成情况进行了对比,发现PFOA在人体中消除速度要高于PFOS和PFHxS. 有学者对氟化工厂周边居民血液中PFOA的暴露水平进行了研究,其研究组分为住宅地址距离工厂1 km、2 km、2—6.50 km及6.50 km以外等4组,研究结果表明,1 km组PFOA浓度最高,中位数浓度达10.20 ng·mL−1,最高检出浓度达到了147 ng·mL−1,且在研究人群血液中PFASs浓度与氟化工厂距离之间呈负相关性[37].将职业人群与普通人群血液中PFASs的检出状况和暴露水平进行比较,职业人群血液中PFASs浓度要比普通人群高1—2个数量级,PFOA与PFOS在两类人群血液中的检出频率和浓度均处于较高水平. 血液中PFASs浓度在不同国家和地区的差异性,不仅与职业相关,还与食物来源、环境等因素有关. 近年来,血液样品中PFASs的浓度随时间的变化呈下降趋势,这与各国实行控制PFASs生产和使用等相关政策有关. 此外,有学者开展了性别和年龄等因素对血液中PFASs影响的相关研究. 根据中国[38]、加拿大[35]、日本[39]、西班牙[40]、希腊[41]和意大利[42]等国家的学者研究结果表明,男性血液中PFASs含量显著高于女性. 在年龄结构方面,老年人血清中的PFASs浓度显著高于年轻人[43 − 45].

-

PFASs进入人体后,最终会通过尿液或粪便等方式排出体外. 尿液排泄是消除人体中蓄积的PFASs的重要途径[46]. 由于尿液采集方便、采样量大,且对人体不会产生伤害,其在调查人体暴露于有害污染物方面具有可操作性强等优势,适用于人群暴露PFASs的风险评估.

对于普通人群,日常暴露于PFASs浓度相对较低,尿液中PFASs的含量通常在ng·L−1级别. 郭斐斐等[47]采用固相萃取结合超高效液相色谱-串联质谱技术对山西某地区人群尿液样本中12种PFASs进行了检测与分析,研究发现仅PFOA、PFNA、PFDA和PFOS等4种化合物有检出;尿液中PFOS含量为7.40—47.30 ng·L−1,显著高于其它3种化合物. 基于相同的样品前处理与检测技术,罗新月等[11]检测了40份小学生晨尿样本,共有9种PFASs被检出,∑9PFASs的浓度为4.76—128.40 ng·L−1,平均浓度为8.59 ng·L−1;PFBS和PFOA的浓度相对较高,平均值分别为7.38 ng·L−1和2.69 ng·L−1. Li等[48]对中国香港53份4—6岁儿童尿液样本中7种PFASs进行了分析检测,结果表明,超过32%的尿液样本中有目标化合物检出,∑PFASs浓度范围为0.18—2.97 ng·L−1,PFOA为主要检出物质. 基于两项针对小学生尿液的研究,儿童尿液中PFASs浓度相对较低,主要污染物均为PFOA. Zhang等[49]和Ji等[50]分析了天津市和山西省人群尿液中PFOA和PFOS的浓度,结果表明,两地人群尿液PFOA暴露水平相当,平均浓度分别为11 ng·L−1和12.90 ng·L−1,但山西省人群尿液中PFOS浓度值是天津市的两倍. 值得注意的是,河北省普通人群尿液中PFOA浓度水平达到了81 ng·L−1,显著高于上述两个地区[51]. 如图2(a)所示,河北省普通人群尿液中PFASs的显著高于国内其它地区,这可能与河北省化工、制造行业较发达有关,其开展氟化工业相关的产业较多,且对周边环境产生了一定影响有关. 图2(a)总结了国内普通人群尿液中PFASs暴露水平,图2(b)比较了普通人群尿液中6种主要PFASs的单暴露水平.

与国内的研究结果相比较,国外部分地区人群尿液中PFASs浓度水平普遍相对较高. 例如,西班牙巴塞罗那地区人群尿液中PFBA和PFOA的平均浓度分别为545 ng·L−1和824 ng·L−1,而PFHxS的平均浓度更是高达

11889 ng·L-1[52]. 在韩国,Kim等[53]发现尿样中以PFPeA为主要污染物质,儿童和成人尿样中PFPeA的平均浓度分别为2340 ng·L−1和2490 ng·L−1. 因此,不同国家和地区人群尿样中的PFASs检出种类和浓度水平呈现一定的空间差异. -

母乳为婴儿提供了几乎所有必要的营养物质,同时也是婴儿接触环境化学物质的主要途径之一. 因此,母乳中有毒化合物的浓度,对婴儿发育和健康会造成潜在的不利影响,已越来越多地引起了人们的广泛关注. 当前,已有多个国家的母乳样品中检测到了不同浓度水平的PFASs.

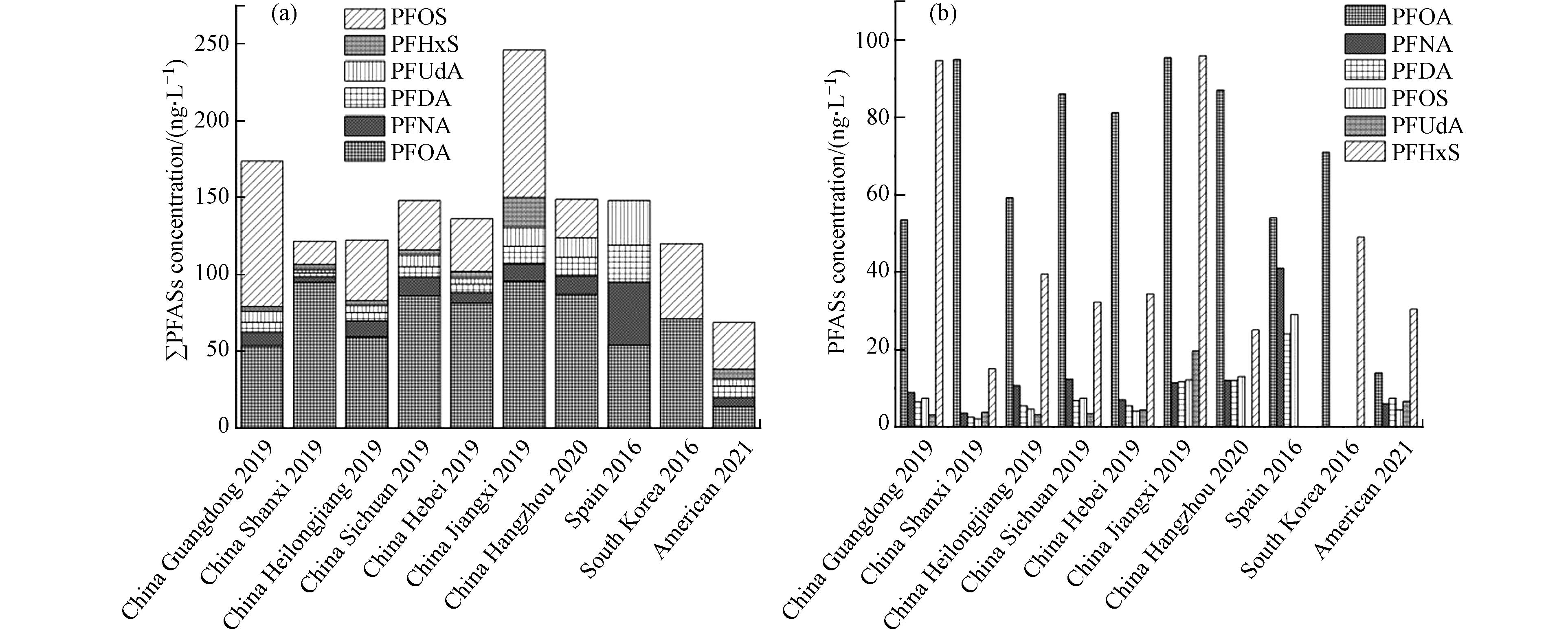

国内研究中,刘嘉颖[54]于2009年研究了我国12个不同地区母乳样品中PFASs的含量,共有6种PFASs被检出,其中PFOA和PFOS为含量最高的两种物质;上海市母乳样品中PFASs含量最高,∑6PFASs浓度均值为

1044 ng·L−1,其次为辽宁省(334 ng·L−1)和福建省(222 ng·L−1),宁夏回族自治区母乳样品中PFASs含量最低,仅31 ng·L−1,这反映了PFASs浓度与各省市工业化和城市化程度存在一定关系. 在2017—2020年,从第三次全国母乳调查结果显示,对来自24个省的100份混合母乳样本中的30种PFASs进行了检测,结果显示母乳中主要的PFASs为PFOA和PFOS,其平均浓度分别为151、57 ng·L−1[55]. 从全国母乳PFASs暴露水平调查的结果来看,上海(490 ng·L−1)和辽宁(205 ng·L−1)等老工业区的PFASs暴露量大幅下降,但山东(1009 ng·L−1)和湖北(317 ng·L−1)等地PFASs暴露量较高,而其它省份母乳PFASs暴露量也各有差异,如广东(195 ng·L−1)、山西(128 ng·L−1)、黑龙江(133 ng·L−1)、四川(164 ng·L−1)、河北(151 ng·L−1)、江西(281 ng·L−1)等,这进一步反映了PFASs浓度与各省市工业化和城市化程度存在一定关系. Jin等[56]研究了母乳中PFASs浓度及其与婴儿出生后生长发育的关系,该研究主要通过对杭州市地区174名妇女母乳中16种PFASs进行检测与分析,探讨母乳中这些PFASs与婴儿出生后生长发育的关系,并首次报道了中国人群母乳中Cl-PFESAs的暴露水平. 结果表明,母乳中的PFOA含量最高,平均浓度为87 ng·L−1,其次是PFHxS和6:2全氟聚醚磺酸(6:2 Cl-PFESAs),平均浓度分别为41 ng·L−1和28 ng·L−1;母乳中PFOA、PFDA、PFNA和6:2Cl-PFESAs浓度与婴儿身长增重率呈负相关关系,而暴露于较高水平的8:2氟调聚醇(8:2 FTOH)与婴儿增重率下降有关. 该研究首次证明,通过哺乳期母乳接触5种化合物会影响婴儿的生长发育.国外研究中,von Ehrenstein等[57]对美国北卡罗来纳州的34名哺乳妇女母乳中PFASs进行了研究,研究结果表明,在多数母乳样品中,PFASs低于定量限,仅有3种PFASs有检出. Zheng等[58]对美国50份母乳样品中的39种PFASs进行了检测分析,共有16种PFASs被检出,母乳中∑16PFASs的浓度范围为52—1850 ng·L−1,PFOS(中位值:30.40 ng·L−1)和PFOA(中位值:13.90 ng·L−1)含量最高;两种短链PFHxA和PFHpA在多数样品中也有检出,中位值分别为9.69 ng·L−1和6.10 ng·L−1. 在西班牙,Motas等[23]对67份母乳样品中的PFASs进行了检测分析,PFOA、PFNA、PFDA、PFUdA和PFDoA等5种化合物在50份样品中全部有检出;∑5PFASs的浓度范围为10—397 ng·L−1,平均值为66 ng·L−1;此外,该研究发现初次分娩者的母乳中PFOA浓度相对较高. 在韩国,Kang等[59]对264名韩国哺乳期妇女的母乳样本中24种PFASs进行了检测,其中,98.50%的母乳样品中检出PFOA和PFOS,中位数浓度值分别为72 ng·L−1和50 ng·L−1. 该研究发现,随着哺乳时间增加,母乳中短链PFCAs的浓度越高,而PFOA的浓度则相反,表明母乳喂养可能是哺乳期妇女PFOA排出的重要途径. 同时,饮食和日常消费品,如护肤品、化妆品和不粘涂层烹饪用具,都认为是母乳中PFASs重要来源. 在一项早期的研究中,Tao等[60]对亚洲7个国家共184个母乳样品中的9种PFASs进行了检测分析,结果表明,PFOS为主要的污染物,几乎在所有的母乳样本中均有检出. 当前,母乳中PFASs的浓度相对较低,尚不会对婴儿健康产生影响[61 − 63]. 但是,近年来母乳中PFASs的检出率和浓度都有所上升,其对婴儿造成的潜在风险仍需重视. 图3(a)总结了国内外普通人群母乳中PFASs暴露水平,图3(b)比较了普通人群母乳中6种主要PFASs的单暴露水平.

母乳中PFASs浓度与女性怀孕的次数之间还存在一定的相关性. 一般情况下,首胎出生的婴幼儿与之后出生的婴幼儿相比,其通过母乳会接触更高的PFASs暴露剂量. 研究表明怀孕间隔时间对母乳中PFASs的暴露水平也有影响. Whitworth等[64]通过研究发现如果两次分娩之间的间隔时间过长,第二次母乳中PFASs的暴露水平可能与第一次哺乳时一样高,原因可能是因为母体通过长期母乳喂养来净化和排出这些化学物质所导致.

-

头发和指甲作为非损伤性生物基质,因其具有易采集、贮存、运输,且能够反映长期暴露并对暴露历史进行追溯等特点,已广泛应用于微量元素检测、疾病诊断等领域[65 − 68]. 近年来,已有学者将头发、指甲应用于人体PFASs暴露评价方面的研究.

高倍等[69]将头发作为暴露指示物,调查了大连地区20岁以上不同年龄层人群中PFASs赋存情况,共有7种PFASs被检出,其中6种化合物的检出率均为100%,∑7PFASs浓度范围为33.70—50.30 ng·g−1. 该研究同时以指甲作为暴露指示物,调查了全国10个城市大学生PFASs赋存情况,结果表明,指甲中∑7PFASs浓度范围为6.95—27.80 ng·g−1,不同地区之间存在显著的地域性差异;其中PFNA是指甲中主要的污染物. Li等[48]对中国香港53份4至6岁儿童头发样本中7种PFASs进行了分析检测,结果表明,超过48%的头发样本中有PFASs检出,∑7PFASs浓度范围为2.40—233 pg·g−1,其主要污染物为PFOA. Wang等[70]对武汉地区渔业从业人员和石家庄普通居民的指甲样本进行了研究,结果表明,在武汉地区渔业人群指甲样本中,PFOS是检测浓度最高的物质,浓度范围为57.40—480 ng·g−1,平均浓度为239 ng·g−1;而从石家庄普通人群指甲样本中PFOA是检测浓度最高的物质,浓度范围为0.77—21.20 ng·g−1,平均浓度为10.20 ng·g−1. 基于两类人群检测结果的不同,职业是造成这类差异的重要因素. 姚丹等[71]研究了天津地区33例头发和指甲中PFASs的赋存情况,头发、指甲中∑PFSAs平均值分别为34 ng·g−1和38 ng·g−1;其中,中链PFASs分别占头发和指甲中PFASs总量的60%和63%,短链PFASs分别占39%和37%,而长链PFASs仅有PFudA和PFTrDA被检出.

当前,人体头发和指甲中PFASs的来源尚不清楚,其可能来源包括血液、汗液或皮脂分泌物迁移到头发中,以及空气或灰尘等外部环境的直接影响[72 − 76]. 因此,将头发和指甲作为样本来探究PFASs暴露水平的研究相对较少. 但与尿液和血液采样相比,头发和指甲在采样、运输和存储方面具有明显的优势. 通过内部暴露或是外部暴露,其都有助于在头发中掺入PFASs,未有准确的方法来确定哪种来源占主导地位. 因此,在对人体生物样本中PFASs监测时,采用头发作为研究对象尚具有一定的局限性,其无法科学地反映PFASs在人体中的赋存情况[77 − 83]. 目前头发指甲相关数据极其有限,还需要进一步深入研究.

-

经研究调查显示,人体生物样品中PFASs含量与人群职业、性别、不同年龄组成等因素有关. Sunderland等[84]在2019年就PFASs暴露水平与职业的相关性展开了调查,发现多个行业从业人员长期接触PFASs导致体内PFASs水平上升,主要包括氟化学品生产工人、消防员、滑雪蜡技师和金属板材行业工人等. 该研究同时发现非职业人群接触PFASs的暴露途径主要是受PFASs污染的饮用水、食物、粉尘吸入有关[85 − 92]. 从性别的角度来看,女性体内PFASs的浓度通常低于男性[93 − 95]. 相比于男性,女性体内PFASs的半衰期较短,这归因于女性通过月经、怀孕期间胎盘转移、以及母乳喂养等方式将PFASs排出体外[[96 − 97].

有学者调查了人体血液中PFASs浓度与年龄的关系,在韩国[98]、挪威[99]、中国[100]、日本[101]等研究中都证明人血液中的PFASs浓度与年龄呈正相关,即随着年龄的增长PFASs浓度呈现增加的趋势. 其中,老年人群中PFASs水平较高的主要原因是长期通过食物摄入PFASs,以及体内新陈代谢排出、清除PFASs的速率变慢等所导致[102].

除了外部原因外,PFASs结构的差异性,如PFASs碳链长度及官能团的不同,也会使其在人体内的含量和分布存在差异. 有研究发现对于相同碳链的PFASs,PFSAs在人体内的半衰期相较于PFCAs更长[103 − 104],更易在人体内蓄积. 有学者对高暴露职业人群进行了研究调查,以评估PFASs在人体中的含量变化,研究结果表明,相较于长链PFASs,短链PFASs与肾脏有机阴离子转运蛋白的结合亲和力较低[105],而且由于短链PFASs分子量较小,使其更容易通过细胞膜,在人体内较易蓄积[106].

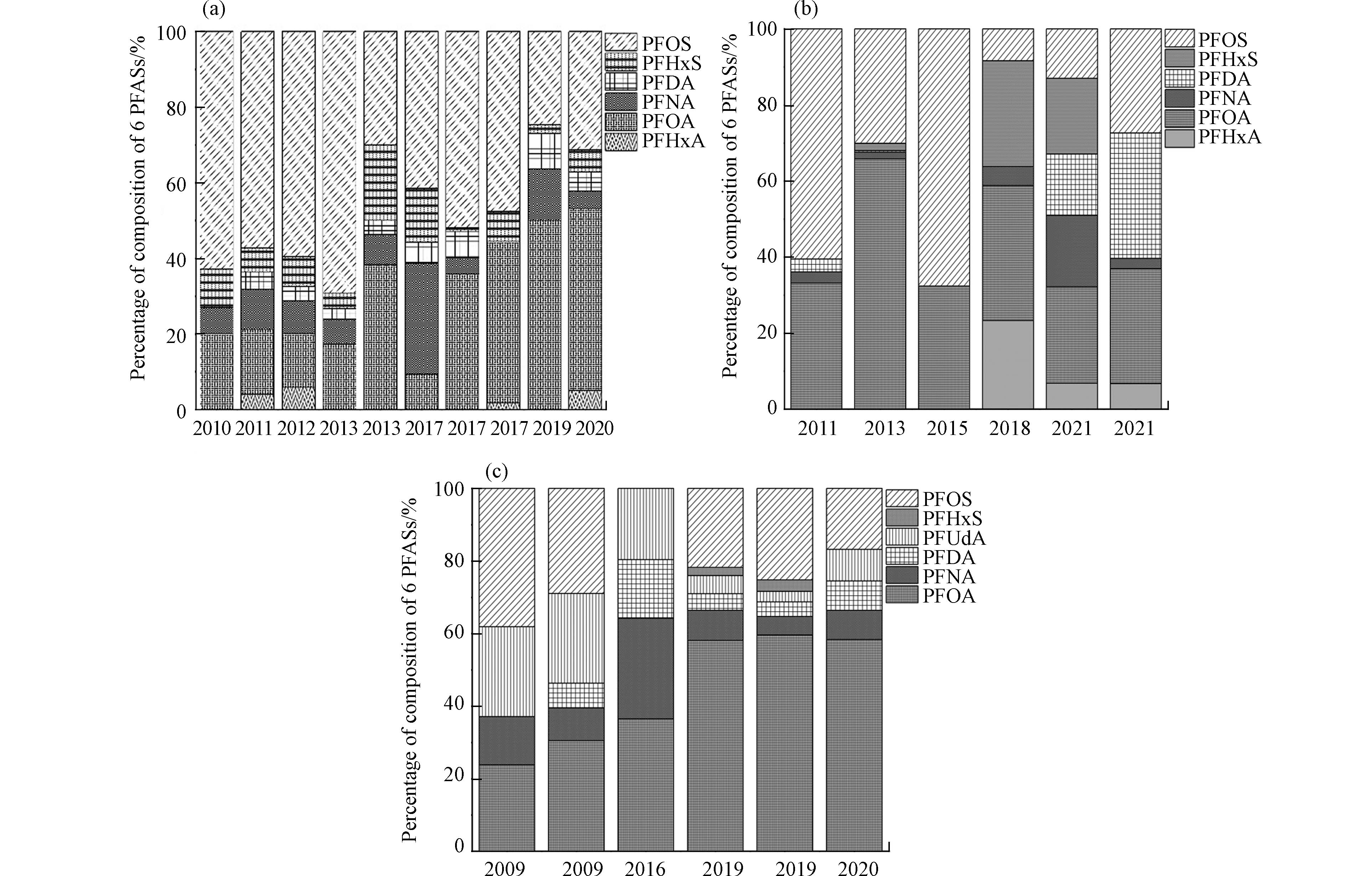

全球范围内,血液、尿液、母乳中检出浓度较高的6种PFASs的组成成分由图4所示. 在3种人体生物样本中,PFOA和PFOS都是主要的检出物质. 其中,PFOS在血液、尿液和母乳中的组成占比,呈现逐年下降的趋势;而PFOA在血液和母乳中的组成占比,呈现逐年上升的趋势,在尿液中则没有变化趋势.

-

PFASs是一类新污染物,已在人体生物样本中被广泛检出[107 − 108]. 目前,国内外学者们已针对人体生物样本中痕量PFASs的检测与分析开展了大量的研究,建立灵敏度高、稳定性好的分析检测方法,但仍有许多的问题需要解决. 无创、少量采样、前处理流程简便,是人体生物样品中PFASs检测方法的发展趋势.

现阶段对于人体生物样本中PFASs的检测工作,多集中在血液和尿液样品,针对母乳、头发和指甲的研究相对较少. 人体生物样本中PFASs暴露水平,血液>母乳>尿液>头发和指甲. 研究区域人群的饮食特征、饮用水来源、工业化水平都是导致人体中PFASs浓度产生差异的重要原因,特别是氟工业园区以及PFASs有关产业园区周边生活的居民,其体内PFASs浓度较其他地区人群中PFASs浓度会高1—2个数量级. 此外,人体血液和尿液中PFASs的浓度可能与年龄、性别和其他因素有关,包括饮食习惯、生活方式及体重指数等. 然而,针对尿液样本的采集存在一定争议,如样本采集的时间点造成的偏差. 尽管24 h尿样可以提供更具代表性的内部接触衡量标准,但这也会增加样本收集的难度. 母乳中的PFASs水平总体上远低于人类血液中的水平,这可能是因为PFASs从女性的血液转移到母乳的比率很低. 对于头发、指甲的研究仍然局限于使用其作为一种有前途的非侵入性方法来进行PFASs生物监测,但并未就此展开大量研究. 近年来,短链PFASs在环境介质中的检出浓度逐渐增高,但其在人体生物样本中的报道相对较少,关于新兴未知的PFASs及其替代品则鲜有报道. 因此,关于短链PFASs、以及新兴未知的PFASs在人体中的残留水平、代谢特征、以及生物毒性,是当前PFASs人体健康风险评估工作中需要研究的重点.

全氟和多氟烷基物质在人体生物样本中的检测方法与暴露水平研究进展

Progress in the determination methods and exposure levels of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances in human biological samples

-

摘要: 全氟和多氟烷基物质(PFASs)是一类人工合成的化学物质,在环境介质和人体生物样本中被广泛检出. 本文针对人体血液、尿液、母乳、头发和指甲等5种人体生物样本,总结了PFASs的前处理方法和仪器分析方法,介绍了国内外关于人体生物样本中PFASs暴露水平的最新研究进展,展望了这一领域的发展方向. 通过研究结果显示,PFASs在普通人群5种样本中的检出情况为血液>母乳>尿液>头发和指甲,人群的饮食特征、饮用水来源、研究区域工业化水平等均为影响PFASs暴露水平的重要因素,且研究发现从事相关行业的职业人群或相关行业周边居住居民其体内PFASs暴露水平比普通人群普遍高1—2个数量级. 在5种人体生物样本中,PFOA和PFOS均为检出浓度较高的物质. 本文旨在为今后关于PFASs的人体暴露和检测分析提供参考,为国家和地区人体生物监测提供技术支撑.Abstract: Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) are a class of synthetic chemicals, which are widely detected in environmental media and human biological samples. In this paper, the pretreatment methods and instrumental analysis methods of PFASs for five types of human biological samples, including human blood, urine, breast milk, hair and nails, were summarized. In addition, the latest research progress on the exposure level of PFASs in human biological samples at home and abroad is introduced, and the development direction in this field is prospected. The results of the study showed that PFASs were detected in five types of samples from the general population: blood>breast milk>urine>hair and nails, and that the dietary characteristics of the population, the source of drinking water, and the level of industrialization in the study area were all important factors influencing the level of exposure to PFASs, and it was found that the level of exposure of occupational groups engaged in the relevant industries or living in the vicinity of the relevant industries was generally one to two orders of magnitude higher than that of the general population. In addition, it was found that the exposure level of PFASs in the occupational groups or residents living in the vicinity of the relevant industries was one to two orders of magnitude higher than that in the general population. PFOA and PFOS were detected at high concentrations in five types of human biological samples. This paper aims to provide reference for human exposure and detection analysis of PFASs in the future, and provide technical support for national and regional human biological monitoring.

-

-

表 1 主要PFASs名称、CAS号、缩写及分子式

Table 1. Names, CAS numbers, abbreviations and molecular formulae of major PFASs

化合物

CompoundCAS号

CAS number简称/缩写

Abbreviations/Acronyms分子式

Molecular formula全氟丁酸 375-22-4 PFBA C4HF7O2 全氟戊酸 2706 -90-3PFPeA C5HF9O2 全氟己酸 307-24-4 PFHxA C6HF11O2 全氟庚酸 375-85-9 PFHpA C7HF13O2 全氟辛酸 335-67-1 PFOA C8HF15O2 全氟壬酸 375-95-1 PFNA C9HF17O2 全氟癸酸 335-76-2 PFDA C10HF19O2 全氟十一烷酸 2058 -94-8PFUdA C11HF21O2 全氟十二烷酸 307-55-1 PFDoA C12HF23O2 全氟十三烷酸 72629 -94-8PFTrDA C13HF25O2 全氟十四烷酸 376-06-7 PFTeDA C14HF27O2 全氟十六烷酸 67905 -19-5PFHxDA C16HF31O2 全氟十八烷酸 16517 -11-6PFoDA C18HF35O2 全氟丁烷磺酸 375-73-5 PFBS C4HF9SO3 全氟戊烷磺酸 2706 -91-4PFPeS C5HF11O3S 全氟己烷磺酸 355-46-4 PFHxS C6HF13SO3 全氟庚烷磺酸 375-92-8 PFHpS C7HF15O3S 全氟辛烷磺酸 1763 -23-1PFOS C8HF17SO3 全氟壬烷磺酸 474511 -07-4PFNS C9F19O3S 全氟癸烷磺酸 335-77-3 PFDS C10HF21SO3 全氟十二烷磺酸 79780 -39-5PFDoS C12HF25O3S 表 2 人体生物样本中PFASs前处理方法的优缺点

Table 2. Advantages and disadvantages of pre-treatment methods for PFASs in human biological samples

前处理方法

Pre-treatment methods优点

Advantages缺点

Disadvantages固相萃取 节约大量有机溶剂、回收率高、引入污染小 过程繁琐、成本高 离子对萃取 萃取速度快、试剂少 易引入污染 碱消解 方法简单 耗时长 加速溶剂萃取 萃取速度快、回收率高 所需样品量大 固相微萃取 操作简单、萃取速度快 成本高 表 3 人体生物样本中PFASs不同前处理方法比较

Table 3. Comparison of different pre-treatment methods for PFASs in human biological samples

编号

Numbers全氟化合物

PFASs样本

Sample样本量

Sample

size前处理方法

Pre-treatment

methods加标回收率/%

Spiked recovery

rate方法检出限/

(ng·L−1)

Method detection

limit方法定量限/

(ng·mL−1)

Method limit

of quantification参考文献

Reference1 12种PFASs 尿液 10 mL 固相萃取(WAX柱) 91.50—114 0.032—6.50 0.0001 —0.021[11] 2 4种PFASs 血液 5 µL 硅微流控芯片-固相萃取 88.70—107 0.050—0.20 — [12] 3 43种PFASs 血液 25 µL 在线固相萃取 84.30—109 0.013—0.089 — [13] 4 18种PFASs 血液 200 µL 离子对萃取 71.40—119 0.010—0.10 0.050—0.50 [14] 5 17种PFASs 血液 500 µL 离子对萃取 81.80—134 0.020—0.080 0.040—2.23 [15] 6 11种PFASs 母乳 2 mL 碱消解 69—94 1—50 — [16] 7 9种PFASs 血液 — ASE萃取 74.60—128.80 1.10—25.10 0.0030 —0.075[17] 8 3种PFASs 血液、母乳 400 µL 固相微萃取 — 175—350 — [19] 9 8种PFASs 血液、母乳 1 mL 固相微萃取 76—86 0.060—0.59 0.00010 —0.0020 [20] 10 14种PFASs 尿液 500 µL QuEChERS 82—114 0.020—1.28 — [22] -

[1] HU X C, ANDREWS D Q, LINDSTROM A B, et al. Detection of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in U. S. drinking water linked to industrial sites, military fire training areas, and wastewater treatment plants[J]. Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 2016, 3(10): 344-350. [2] WANG Z Y, COUSINS I T, SCHERINGER M, et al. Global emission inventories for C4-C14 perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acid (PFCA) homologues from 1951 to 2030, Part I: Production and emissions from quantifiable sources[J]. Environment International, 2014, 70: 62-75. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2014.04.013 [3] KURWADKAR S, DANE J, KANEL S R, et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in water and wastewater: A critical review of their global occurrence and distribution[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2022, 809: 151003. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151003 [4] WANG Y X, ZHONG Y X, LI J G, et al. Occurrence of perfluoroalkyl substances in matched human serum, urine, hair and nail[J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2018, 67: 191-197. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2017.08.017 [5] GEBBINK W A, GLYNN A, DARNERUD P O, et al. Perfluoroalkyl acids and their precursors in Swedish food: The relative importance of direct and indirect dietary exposure[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2015, 198: 108-115. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2014.12.022 [6] RAND A A, ROONEY J P, BUTT C M, et al. Cellular toxicity associated with exposure to perfluorinated carboxylates (PFCAs) and their metabolic precursors[J]. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 2014, 27(1): 42-50. doi: 10.1021/tx400317p [7] HAGENAARS A, VERGAUWEN L, de COEN W, et al. Structure-activity relationship assessment of four perfluorinated chemicals using a prolonged zebrafish early life stage test[J]. Chemosphere, 2011, 82(5): 764-772. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.10.076 [8] PENG L, XU W, ZENG Q H, et al. Exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances in waste recycling workers: Distributions in paired human serum and urine[J]. Environment International, 2022, 158: 106963. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106963 [9] Programme United Nations Environment. New POPs SC-4/17: Listing of perfluorooctane sulfonic acid, its salts and perfluorooctane sulfonyl fluoride[R]. 2010. [10] CAO Z J, LIN S B, ZHAO F, et al. Cohort profile: China National Human Biomonitoring (CNHBM)—a nationally representative, prospective cohort in Chinese population[J]. Environment International, 2021, 146: 106252. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106252 [11] 罗新月, 赵璇, 任琳, 等. 尿液中12种全氟化合物的固相萃取-超高效液相色谱串联四极杆线性离子阱质谱分析方法研究[J]. 四川大学学报(医学版), 2021, 52(4): 679-685. LUO X Y, ZHAO X, REN L, et al. Study on the analytical method of solid phase extraction-ultra performance liquid chromatography tandem quadrupole linear ion trap mass spectrometry for 12 perfluorinated compounds in human urine[J]. Journal of Sichuan University (Medical Sciences), 2021, 52(4): 679-685 (in Chinese).

[12] MAO P, WANG D J. Biomonitoring of perfluorinated compounds in a drop of blood[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2015, 49(11): 6808-6814. [13] GAO K, FU J J, XUE Q, et al. An integrated method for simultaneously determining 10 classes of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in one drop of human serum[J]. Analytica Chimica Acta, 2018, 999: 76-86. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2017.10.038 [14] 谢琳娜, 张海婧, 侯沙沙, 等. 人血清中18种全氟烷烃化合物 UPLC-MS/MS的测定[J]. 环境卫生学杂志, 2019, 9(5): 494-501. XIE L N, ZHANG H J, HOU S S, et al. Determination of 18 perfluoroalkyl substances in human serum by UPLC-MS/MS[J]. Journal of Environmental Hygiene, 2019, 9(5): 494-501 (in Chinese).

[15] WU M H, SUN R, WANG M N, et al. Analysis of perfluorinated compounds in human serum from the general population in Shanghai by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)[J]. Chemosphere, 2017, 168: 100-105. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.09.161 [16] SO M K, TANIYASU S, LAM P K S, et al. Alkaline digestion and solid phase extraction method for perfluorinated compounds in mussels and oysters from South China and Japan[J]. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2006, 50(2): 240-248. doi: 10.1007/s00244-005-7058-x [17] 宋小飞, 施召才, 马伟文, 等. 液相色谱-质谱联用法测定血液中全氟化合物[J]. 分析试验室, 2020, 39(1): 53-56. SONG X F, SHI Z C, MA W W, et al. Determination of perfluorinated compounds in blood by liquid chromatographymass spectrometry[J]. Chinese Journal of Analysis Laboratory, 2020, 39(1): 53-56 (in Chinese).

[18] 王姮, 胡红美, 郭远明, 等. 水产品中有机锡类化合物检测方法研究进展[J]. 食品安全质量检测学报, 2019, 10(21): 7245-7252. WANG H, HU H M, GUO Y M, et al. Research progress of detection methods of organotin compounds in aquatic products[J]. Journal of Food Safety & Quality, 2019, 10(21): 7245-7252 (in Chinese).

[19] MATHURIN J C, de CEAURRIZ J, AUDRAN M, et al. Detection of perfluorocarbons in blood by headspace solid-phase microextraction combined with gas chromatography/mass spectrometry[J]. Biomedical Chromatography:BMC, 2001, 15(7): 443-451. doi: 10.1002/bmc.79 [20] DENG J W, YANG Y Y, FANG L, et al. Coupling solid-phase microextraction with ambient mass spectrometry using surface coated wooden-tip probe for rapid analysis of ultra trace perfluorinated compounds in complex samples[J]. Analytical Chemistry, 2014, 86(22): 11159-11166. doi: 10.1021/ac5034177 [21] 顾奕, 郭明, 吕达, 等. 毛细管电泳法考察全氟辛酸与人血清白蛋白的相互作用[J]. 色谱, 2018, 36(1): 69-77. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1123.2017.09041 GU Y, GUO M, LV D, et al. Investigation on the interaction between pentadecafluorooctanoic acid and human serum albumin by capillary electrophoresis[J]. Chinese Journal of Chromatography, 2018, 36(1): 69-77 (in Chinese). doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1123.2017.09041

[22] WU N, CAI D M, GUO M J, et al. Per- and polyfluorinated compounds in saleswomen’s urine linked to indoor dust in clothing shops[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 667: 594-600. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.287 [23] MOTAS GUZMÀN M, CLEMENTINI C, PÉREZ-CÁRCELES M D, et al. Perfluorinated carboxylic acids in human breast milk from Spain and estimation of infant’s daily intake[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2016, 544: 595-600. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.11.059 [24] FUJII Y, YAN J X, HARADA K H, et al. Levels and profiles of long-chain perfluorinated carboxylic acids in human breast milk and infant formulas in East Asia[J]. Chemosphere, 2012, 86(3): 315-321. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.10.035 [25] ZHANG J J, JASPERS V L B, RØE J, et al. Per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances in Tawny Owl (Strix aluco) feathers from Trøndelag, Norway[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2023, 903: 166213. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166213 [26] 肖永华, 梁高道, 革丽亚, 等. 固相萃取-超高效液相色谱/串联质谱法测定人体血清中7种全氟化合物[J]. 分析科学学报, 2015, 31(5): 646-650. XIAO Y H, LIANG G D, GE L Y, et al. Determination of seven perfluorinated compounds in human serum by ultra performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry combined with solid phase extraction[J]. Journal of Analytical Science, 2015, 31(5): 646-650 (in Chinese).

[27] LIU D X, TANG B, NIE S S, et al. Distribution of per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances and their precursors in human blood[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2023, 441: 129908. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.129908 [28] LIAO Q, TANG P, PAN D X, et al. Association of serum per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and gestational anemia during different trimesters in Zhuang ethnic pregnancy women of Guangxi, China[J]. Chemosphere, 2022, 309: 136798. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136798 [29] LI Y J, CHENG Y T, XIE Z Y, et al. Perfluorinated alkyl substances in serum of the southern Chinese general population and potential impact on thyroid hormones[J]. Scientific Reports, 2017, 7: 43380. doi: 10.1038/srep43380 [30] ZENG X W, QIAN Z M, VAUGHN M, et al. Human serum levels of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) in Uyghurs from Sinkiang-Uighur Autonomous Region, China: Background levels study[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2015, 22(6): 4736-4746. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-3728-4 [31] GUO F F, ZHONG Y X, WANG Y X, et al. Perfluorinated compounds in human blood around Bohai Sea, China[J]. Chemosphere, 2011, 85(2): 156-162. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.06.038 [32] BJERREGAARD-OLESEN C, BACH C C, LONG M H, et al. Time trends of perfluorinated alkyl acids in serum from Danish pregnant women 2008-2013[J]. Environment International, 2016, 91: 14-21. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.02.010 [33] ERIKSSON U, MUELLER J F, TOMS L M L, et al. Temporal trends of PFSAs, PFCAs and selected precursors in Australian serum from 2002 to 2013[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2017, 220: 168-177. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.09.036 [34] GLEASON J A, POST G B, FAGLIANO J A. Associations of perfluorinated chemical serum concentrations and biomarkers of liver function and uric acid in the US population (NHANES), 2007-2010[J]. Environmental Research, 2015, 136: 8-14. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.10.004 [35] AKER A, AYOTTE P, CARON-BEAUDOIN E, et al. Plasma concentrations of perfluoroalkyl acids and their determinants in youth and adults from Nunavik, Canada[J]. Chemosphere, 2023, 310: 136797. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136797 [36] FU J J, GAO Y, CUI L, et al. Occurrence, temporal trends, and half-lives of perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) in occupational workers in China[J]. Scientific Reports, 2016, 6: 38039. doi: 10.1038/srep38039 [37] GEBBINK W A, van LEEUWEN S P J. Environmental contamination and human exposure to PFASs near a fluorochemical production plant: Review of historic and current PFOA and GenX contamination in the Netherlands[J]. Environment International, 2020, 137: 105583. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105583 [38] YEUNG L W Y, SO M K, JIANG G B, et al. Perfluorooctanesulfonate and related fluorochemicals in human blood samples from China[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2006, 40(3): 715-720. [39] HARADA K, SAITO N, INOUE K, et al. The influence of time, sex and geographic factors on levels of perfluorooctane sulfonate and perfluorooctanoate in human serum over the last 25 years[J]. Journal of Occupational Health, 2004, 46(2): 141-147. doi: 10.1539/joh.46.141 [40] ERICSON I, GÓMEZ M, NADAL M, et al. Perfluorinated chemicals in blood of residents in Catalonia (Spain) in relation to age and gender: A pilot study[J]. Environment International, 2007, 33(5): 616-623. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2007.01.003 [41] VASSILIADOU I, COSTOPOULOU D, FERDERIGOU A, et al. Levels of perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) in blood samples from different groups of adults living in Greece[J]. Chemosphere, 2010, 80(10): 1199-1206. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.06.014 [42] INGELIDO A M, MARRA V, ABBALLE A, et al. Perfluorooctanesulfonate and perfluorooctanoic acid exposures of the Italian general population[J]. Chemosphere, 2010, 80(10): 1125-1130. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.06.025 [43] KÄRRMAN A, van BAVEL B, JÄRNBERG U, et al. Perfluorinated chemicals in relation to other persistent organic pollutants in human blood[J]. Chemosphere, 2006, 64(9): 1582-1591. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.11.040 [44] LIU J Y, LI J G, LUAN Y, et al. Geographical distribution of perfluorinated compounds in human blood from Liaoning Province, China[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2009, 43(11): 4044-4048. [45] NILSSON H, KÄRRMAN A, WESTBERG H, et al. A time trend study of significantly elevated perfluorocarboxylate levels in humans after using fluorinated ski wax[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2010, 44(6): 2150-2155. [46] HARTMANN C, JAMNIK T, WEISS S, et al. Results of the Austrian Children’s Biomonitoring Survey 2020 part A: Per- and polyfluorinated alkylated substances, bisphenols, parabens and other xenobiotics[J]. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 2023, 249: 114123. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2023.114123 [47] 郭斐斐, 王雨昕, 李敬光, 等. 超高效液相色谱-串联质谱法测定人尿液中全氟有机化合物[J]. 色谱, 2011, 29(2): 126-130. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1123.2011.00126 GUO F F, WANG Y X, LI J G, et al. Determination of perfluorinated compounds in human urine by ultra high performance liquid chromatographytandem mass spectrometry[J]. Chinese Journal of Chromatography, 2011, 29(2): 126-130 (in Chinese). doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1123.2011.00126

[48] LI N, YING G G, HONG H C, et al. Perfluoroalkyl substances in the urine and hair of preschool children, airborne particles in kindergartens, and drinking water in Hongkong[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 270: 116219. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.116219 [49] ZHANG T, SUN H W, QIN X L, et al. PFOS and PFOA in paired urine and blood from general adults and pregnant women: Assessment of urinary elimination[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2015, 22(7): 5572-5579. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-3725-7 [50] JI K, KIM S, KHO Y, et al. Serum concentrations of major perfluorinated compounds among the general population in Korea: Dietary sources and potential impact on thyroid hormones[J]. Environment International, 2012, 45: 78-85. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2012.03.007 [51] ZHANG Y F, BEESOON S, ZHU L Y, et al. Biomonitoring of perfluoroalkyl acids in human urine and estimates of biological half-life[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2013, 47(18): 10619-10627. [52] PEREZ F, LLORCA M, FARRÉ M, et al. Automated analysis of perfluorinated compounds in human hair and urine samples by turbulent flow chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry[J]. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 2012, 402(7): 2369-2378. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-5660-5 [53] KIM D H, LEE M Y, OH J E. Perfluorinated compounds in serum and urine samples from children aged 5-13 years in South Korea[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2014, 192: 171-178. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2014.05.024 [54] 刘嘉颖. 我国居民典型全氟有机化合物人体暴露水平与暴露途径研究[D]. 北京: 中国疾病预防控制中心, 2009. LIU J Y. Study on exposure level and exposure route of typical perfluoroorganic compounds in Chinese residents[D]. Beijing: Chinese Center For Disease Control And Prevention, 2009 (in Chinese).

[55] HAN F, WANG Y X, LI J G, et al. Occurrences of legacy and emerging per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in human milk in China: Results of the third National Human Milk Survey (2017-2020)[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2023, 443: 130163. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.130163 [56] JIN H B, MAO L L, XIE J H, et al. Poly- and perfluoroalkyl substance concentrations in human breast milk and their associations with postnatal infant growth[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 713: 136417. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136417 [57] von EHRENSTEIN O S, FENTON S E, KATO K, et al. Polyfluoroalkyl chemicals in the serum and milk of breastfeeding women[J]. Reproductive Toxicology, 2009, 27(3/4): 239-245. [58] ZHENG G M, SCHREDER E, DEMPSEY J C, et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in breast milk: Concerning trends for current-use PFAS[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2021, 55(11): 7510-7520. [59] KANG H, CHOI K, LEE H S, et al. Elevated levels of short carbon-chain PFCAs in breast milk among Korean women: Current status and potential challenges[J]. Environmental Research, 2016, 148: 351-359. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2016.04.017 [60] TAO L, MA J, KUNISUE T, et al. Perfluorinated compounds in human breast milk from several Asian countries, and in infant formula and dairy milk from the United States[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2008, 42(22): 8597-8602. [61] TYSMAN M, TOPPARI J, MAIN K M, et al. Levels of persistent organic pollutants in breast milk samples representing Finnish and Danish boys with and without hypospadias[J]. Chemosphere, 2023, 313: 137343. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.137343 [62] 夏慧. 全氟化合物的暴露风险及其与人体功能蛋白相互作用的研究[D]. 上海: 上海交通大学, 2018. XIA H. Study on the exposure risk of perfluorochemicals and their interaction with human functional proteins[D]. Shanghai: Shanghai Jiao Tong University, 2018 (in Chinese).

[63] LIU J Y, LI J G, ZHAO Y F, et al. The occurrence of perfluorinated alkyl compounds in human milk from different regions of China[J]. Environment International, 2010, 36(5): 433-438. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2010.03.004 [64] WHITWORTH K W, HAUG L S, BAIRD D D, et al. Perfluorinated compounds and subfecundity in pregnant women[J]. Epidemiology, 2012, 23(2): 257-263. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31823b5031 [65] ASHRAP P, WATKINS D J, CALAFAT A M, et al. Elevated concentrations of urinary triclocarban, phenol and paraben among pregnant women in Northern Puerto Rico: Predictors and trends[J]. Environment International, 2018, 121: 990-1002. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.08.020 [66] RAZA N, KIM K H, ABDULLAH M, et al. Recent developments in analytical quantitation approaches for parabens in human-associated samples[J]. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2018, 98: 161-173. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2017.11.009 [67] BROCKMAN J D, ROBERTSON J D, MORRIS J S, et al. Nail as a biomarker of selenium and methyl mercury in a rat model[J]. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry, 2008, 276(1): 59-64. doi: 10.1007/s10967-007-0410-z [68] JIAN J M, GUO Y, ZENG L X, et al. Global distribution of perfluorochemicals (PFCs) in potential human exposure source-a review[J]. Environment International, 2017, 108: 51-62. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.07.024 [69] 高倍. 头发指甲作为人类全氟化合物暴露评价指示物的研究[D]. 大连: 大连理工大学, 2014. GAO B. Study on hair nails as indicators for evaluating the exposure of human perfluorinated compounds[D]. Dalian: Dalian University of Technology, 2014 (in Chinese).

[70] WANG Y, SHI Y L, VESTERGREN R, et al. Using hair, nail and urine samples for human exposure assessment of legacy and emerging per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 636: 383-391. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.04.279 [71] 姚丹, 张鸿, 柴之芳, 等. 天津成人头发指甲中有机氟污染物的残留特征[J]. 环境科学, 2013, 34(2): 718-723. YAO D, ZHANG H, CHAI Z F, et al. Residue of organic fluorine pollutants in hair and nails collected from Tianjin[J]. Environmental Science, 2013, 34(2): 718-723 (in Chinese).

[72] MARTIN J W, MABURY S A, SOLOMON K R, et al. Dietary accumulation of perfluorinated acids in juvenile rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)[J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2003, 22(1): 189-195. doi: 10.1002/etc.5620220125 [73] LI J G, GUO F F, WANG Y X, et al. Development of extraction methods for the analysis of perfluorinated compounds in human hair and nail by high performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry[J]. Journal of Chromatography A, 2012, 1219: 54-60. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.11.015 [74] CLAESSENS J, PIRARD C, CHARLIER C. Determination of contamination levels for multiple endocrine disruptors in hair from a non-occupationally exposed population living in Liege (Belgium)[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2022, 815: 152734. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152734 [75] ALVES A, JACOBS G, VANERMEN G, et al. New approach for assessing human perfluoroalkyl exposure via hair[J]. Talanta, 2015, 144: 574-583. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2015.07.009 [76] HENDERSON G L. Mechanisms of drug incorporation into hair[J]. Forensic Science International, 1993, 63(1/2/3): 19-29. [77] LI J G, GUO F F, WANG Y X, et al. Can nail, hair and urine be used for biomonitoring of human exposure to perfluorooctane sulfonate and perfluorooctanoic acid?[J]. Environment International, 2013, 53: 47-52. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2012.12.002 [78] ZHANG H, CHAI Z F, SUN H B. Human hair as a potential biomonitor for assessing persistent organic pollutants[J]. Environment International, 2007, 33(5): 685-693. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2007.02.003 [79] LIU W, XU L, LI X A, et al. Human nails analysis as biomarker of exposure to perfluoroalkyl compounds[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2011, 45(19): 8144-8150. [80] HINES E P, MENDOLA P, von EHRENSTEIN O S, et al. Concentrations of environmental phenols and parabens in milk, urine and serum of lactating North Carolina women[J]. Reproductive Toxicology, 2015, 54: 120-128. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2014.11.006 [81] 徐森昊. 基于HPLC-MS/MS人头发中全氟化合物检测方法的建立及应用[D]. 沈阳: 中国医科大学, 2022. XU S H. Establishment and application of detection method of perfluorochemicals in human hair based on HPLC-MS/MS[D]. Shenyang: China Medical University, 2022 (in Chinese).

[82] MARTÍN J, SANTOS J L, APARICIO I, et al. Exposure assessment to parabens, bisphenol A and perfluoroalkyl compounds in children, women and men by hair analysis[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 695: 133864. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.133864 [83] LEE C, KIM C H, KIM S, et al. Simultaneous determination of bisphenol A and estrogens in hair samples by liquid chromatography-electrospray tandem mass spectrometry[J]. Journal of Chromatography B, 2017, 1058: 8-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2017.05.007 [84] SUNDERLAND E M, HU X C, DASSUNCAO C, et al. A review of the pathways of human exposure to poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and present understanding of health effects[J]. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology, 2019, 29(2): 131-147. [85] OLSEN G W, BURRIS J M, EHRESMAN D J, et al. Half-life of serum elimination of perfluorooctanesulfonate, perfluorohexanesulfonate, and perfluorooctanoate in retired fluorochemical production workers[J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2007, 115(9): 1298-1305. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10009 [86] COSTA G, SARTORI S, CONSONNI D. Thirty years of medical surveillance in perfluooctanoic acid production workers[J]. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 2009, 51(3): 364-372. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181965d80 [87] TROWBRIDGE J, GERONA R R, LIN T, et al. Exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances in a cohort of women firefighters and office workers in San francisco[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2020, 54(6): 3363-3374. [88] NAILA K, DUCATMAN ALAN M, SHRIPAD S, et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance and cardio metabolic markers in firefighters[J]. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 2020, 62(12): 1076-1081. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002062 [89] LEARY D B, TAKAZAWA M, KANNAN K, et al. Perfluoroalkyl substances and metabolic syndrome in firefighters: A pilot study[J]. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 2020, 62(1): 52-57. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001756 [90] ENGELSMAN M, TOMS L M L, BANKS A P W, et al. Biomonitoring in firefighters for volatile organic compounds, semivolatile organic compounds, persistent organic pollutants, and metals: A systematic review[J]. Environmental Research, 2020, 188: 109562. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109562 [91] RUSSELL M H, HIMMELSTEIN M W, BUCK R C. Inhalation and oral toxicokinetics of 6: 2 FTOH and its metabolites in mammals[J]. Chemosphere, 2015, 120: 328-335. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.07.092 [92] SHI Y L, VESTERGREN R, XU L, et al. Human exposure and elimination kinetics of chlorinated polyfluoroalkyl ether sulfonic acids (Cl-PFESAs)[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2016, 50(5): 2396-2404. [93] OLSEN G W, CHURCH T R, MILLER J P, et al. Perfluorooctanesulfonate and other fluorochemicals in the serum of American Red Cross adult blood donors[J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2003, 111(16): 1892-1901. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6316 [94] CALAFAT A M, NEEDHAM L L, KUKLENYIK Z, et al. Perfluorinated chemicals in selected residents of the American continent[J]. Chemosphere, 2006, 63(3): 490-496. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.08.028 [95] KÄRRMAN A, ERICSON I, van BAVEL B, et al. Exposure of perfluorinated chemicals through lactation: Levels of matched human milk and serum and a temporal trend, 1996–2004, in Sweden[J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2007, 115(2): 226-230. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9491 [96] WONG F, MacLEOD M, MUELLER J F, et al. Enhanced elimination of perfluorooctane sulfonic acid by menstruating women: Evidence from population-based pharmacokinetic modeling[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2014, 48(15): 8807-8814. [97] KIM H Y, KIM S K, KANG D M, et al. The relationships between sixteen perfluorinated compound concentrations in blood serum and food, and other parameters, in the general population of South Korea with proportionate stratified sampling method[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2014, 470/471: 1390-1400. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.06.039 [98] CHO C R, LAM N H, CHO B M, et al. Concentration and correlations of perfluoroalkyl substances in whole blood among subjects from three different geographical areas in Korea[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2015, 512/513: 397-405. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.01.070 [99] HAUG L S, THOMSEN C, BRANTSÆTER A L, et al. Diet and particularly seafood are major sources of perfluorinated compounds in humans[J]. Environment International, 2010, 36(7): 772-778. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2010.05.016 [100] FU Y N, WANG T Y, WANG P, et al. Effects of age, gender and region on serum concentrations of perfluorinated compounds in general population of Henan, China[J]. Chemosphere, 2014, 110: 104-110. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.02.020 [101] HARADA K H, YANG H R, MOON C S, et al. Levels of perfluorooctane sulfonate and perfluorooctanoic acid in female serum samples from Japan in 2008, Korea in 1994-2008 and Vietnam in 2007-2008[J]. Chemosphere, 2010, 79(3): 314-319. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.01.027 [102] GULKOWSKA A, JIANG Q T, SO M K, et al. Persistent perfluorinated acids in seafood collected from two cities of China[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2006, 40(12): 3736-3741. [103] LI Y, FLETCHER T, MUCS D, et al. Half-lives of PFOS, PFHxS and PFOA after end of exposure to contaminated drinking water[J]. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 2018, 75(1): 46-51. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2017-104651 [104] XU Y Y, FLETCHER T, PINEDA D, et al. Serum half-lives for short- and long-chain perfluoroalkyl acids after ceasing exposure from drinking water contaminated by firefighting foam[J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2020, 128(7): 77004. doi: 10.1289/EHP6785 [105] HAN X, NABB D L, RUSSELL M H, et al. Renal elimination of perfluorocarboxylates (PFCAs)[J]. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 2012, 25(1): 35-46. doi: 10.1021/tx200363w [106] KIM S K, LEE K T, KANG C S, et al. Distribution of perfluorochemicals between sera and milk from the same mothers and implications for prenatal and postnatal exposures[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2011, 159(1): 169-174. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2010.09.008 [107] KIM D H, LEE J H, OH J E. Perfluoroalkyl acids in paired serum, urine, and hair samples: Correlations with demographic factors and dietary habits[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2019, 248: 175-182. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.02.017 [108] HAN F, LIU J Y, WANG Y X, et al. Penetration of perfluorooctanesulfonate isomers and their alternatives from maternal blood to milk and its associations with chemical properties and milk primary components[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2023, 57(6): 2457-2463. -

下载:

下载: