-

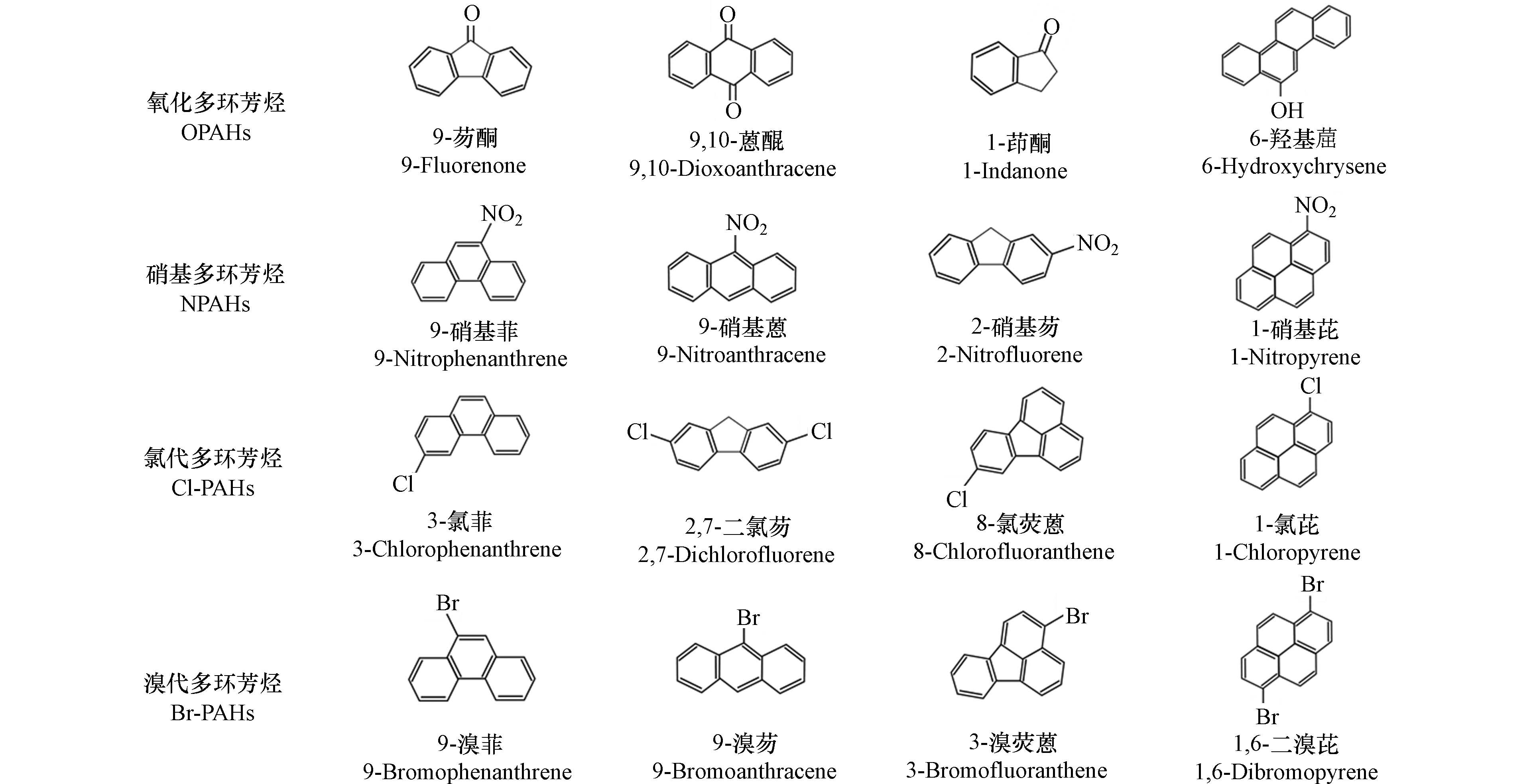

环境中普遍检出的多环芳烃(polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, PAHs),一方面来自生物排放和火山活动等自然过程,另一方面来自燃烧和工业排放等人为活动[1]. 美国环境保护署(the United States Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. EPA)在20世纪70年代公布了16种优先控制PAHs[2],引起了全球范围内的广泛关注和深入研究. 在PAHs产生过程中及其进入环境后,可进一步生成多环芳烃衍生物,如取代多环芳烃(substituted polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, SPAHs)、多环芳烃代谢产物、以及转化降解产物. 其中,SPAHs是多环芳烃衍生物的重要类别,通常指多环芳烃分子结构中苯环上的氢原子或碳原子被其它原子或基团取代后的化合物. 根据取代基团的不同,常见的SPAHs包括氧化多环芳烃(oxygenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, OPAHs)、硝基多环芳烃(nitrated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, NPAHs)、氯代多环芳烃(chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, Cl-PAHs)、溴代多环芳烃(brominated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, Br-PAHs)等(图1为部分化合物的分子结构式).

目前,已在多种环境介质及食物链中检出SPAHs,有些环境中SPAHs的分布水平比PAHs更高. SPAHs不仅广泛分布在水、大气、土壤、沉积物介质中,Minero等[3]在南极大气颗粒物中首次检出NPAHs,证明了SPAHs在全球范围的分布. 此外,SPAHs具有一定的环境持久性,如三环及以上的Cl-PAHs在环境中非常稳定,具有持久性有机污染物多氯联苯和二恶英类似的环境行为[4]. 一项关于污水处理厂中多环芳烃及其衍生物的研究表明,在采集的所有进水和污泥样品中,13种SPAHs总浓度均显著高于16种优控PAHs总浓度[5]. 目前关于SPAHs在食物链中检出的研究报道,多集中在水生生物,包括软体动物和鱼类的肌肉及内脏等[6 − 7]. 在加拿大一个油砂开采区域附近针对植物和动物类食品的分析结果表明,49种SPAHs比16种优控PAHs的检出浓度更高,是当地食物中多环芳烃污染的主要成分,占比范围为63%—95%,而16种优控PAHs的占比为4%—36%[8],说明SPAHs可对食物造成污染.

环境和食物中的SPAHs,可通过呼吸、饮食、皮肤接触等多种途径暴露于人体. 研究表明,SPAHs具有与PAHs相当或比PAHs更强的生物毒性效应. 目前已证实SPAHs可造成DNA损伤,影响生殖发育,且具有致癌、致畸、致突变的“三致”毒性[9]. 有研究将10种HPAHs、27种NPAHs以及38种OPAHs,在斑马鱼胚胎受精后6—120 h进行暴露,并对22个发育终点进行评估,结果表明,三类取代多环芳烃中均有能够引起胚胎发育毒性的物质,NPAHs和OPAHs对斑马鱼胚胎发育的毒性影响相对更强[10 − 11]. 以T. obscurus鱼类为生物模型开展的毒性研究表明,在同样暴露剂量下,氧化多环芳烃9,10-phenanthrenequione与其母体多环芳烃phenanthrene均能引起鱼肝脏损伤以及氧化应激效应,但氧化多环芳烃引起的损伤和效应更强[12]. 以Oryzias melastigma海洋鱼类为模型,发现多环芳烃phenanthrene及其对应的烷基取代多环芳烃retene都能引起胚胎发育畸形,两种化合物引起毒性的原因存在差异,但烷基取代多环芳烃的毒性强于其母体多环芳烃[13]. 综上,具有生物毒性作用的SPAHs,其暴露于人体后引起的健康风险不容忽视.

相较于多环芳烃化合物,针对其衍生物取代多环芳烃的环境分布、毒性作用、健康风险评估等的研究仍然有限. 当评估多环芳烃类物质的健康风险并开展相关污染控制时,若仅考虑多环芳烃母体化合物,忽略环境中广泛分布且具有毒性作用的SPAHs,将造成多环芳烃类污染物的环境健康风险的低估和污染预防控制不足. SPAHs的种类复杂、分析方法多样、易受环境基质干扰,选择合适的样品前处理和分析方法有利于提高检测效率,将促进统一SPAHs的分析标准,并在未来将其纳入常规污染监管. 掌握SPAHs的环境分布现状,能够为污染治理过程中需重点关注的环境提供线索,同时有助于进一步开展相关暴露场景的生物毒性效应研究,指导选择环境相关水平的暴露剂量,模拟真实环境暴露,从而准确评估SPAHs的实际健康风险. 综上,本文针对SPAHs,选择其中四类常见化合物(包括OPAHs、NPAHs、Cl-PAHs以及Br-PAHs),对其环境样品前处理和分析方法进行综述,总结其在不同介质中的分布水平,并对未来的研究趋势进行展望,以期为开展SPAHs的环境分析和基于真实环境的毒理学研究提供依据.

-

环境样品前处理的主要目的,是为了富集浓缩被测组分,同时尽量减少或消除样品基质的干扰,并将被测组分转移到易于检测的介质中. 选择合适的样品前处理方法对于提高分析的灵敏度、准确性和可靠性至关重要[14]. 前处理方法一般包括提取和净化两个部分,二者可同时或分步进行. 在进行样品提取和净化之前,有些类型的环境样品还需要经过简单的制备过程. 例如,水体等液体样品一般需要预先过滤,去除其中的大颗粒物和杂质,而土壤、沉积物、生物、大气颗粒物等固体样品,通常需要经过冷冻干燥脱水并经过研磨成为均质样品后,再继续进行前处理. 对于某些待测组分的提取,还需要调节pH值等操作. 对于不同类型化合物选择前处理方法时,通常需要考虑其理化性质特征. 例如,NPAHs类化合物随分子量和硝基官能团数量增加,其蒸气压和水溶性降低;OPAHs显示出比PAHs更高的极性和水溶性;Cl/Br-PAHs在结构上与二恶英相似,具有类似的物理化学特性[15 − 17]. 对于OPAHs、NPAHs、Cl-PAHs以及Br-PAHs这四类取代多环芳烃,虽然在分子结构上因取代基不同而存在差异,其相似的疏水性和脂溶性使得可以通过同一套前处理方法对不同类型的化合物进行同时提取. 针对SPAHs,常见的前处理方法有液液萃取(liquid-liquid extraction, LLE)、固相萃取(solid-phase extraction, SPE)、索氏萃取(Soxhlet extraction, SE)、加压溶剂萃取(accelerated solvent extraction, ASE)、凝胶渗透色谱(gel permeation chromatography, GPC)等. SPAHs的前处理方法总结见表1.

-

液液萃取(liquid-liquid extraction, LLE)是提取水样中SPAHs的常用方法,其利用目标提取物在水相和有机相溶剂中溶解度不同而达到提取的目的. Zhu等[27]通过优化LLE方法,分别使用己烷∶二氯甲烷(体积比1∶1)的混合溶液以及己烷作为萃取溶剂,提取了地下水中8种OPAHs、4种Cl-PAHs和4种NPAHs,其回收率为54.3%—115.1%,相对标准偏差(relative standard deviation, RSD)小于17.9%,并将该方法应用于华东地区64个地下水样品的筛查研究. 基于LLE的原理,逐渐发展出分散液液微萃取(dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction, DLLME)技术. DLLME采用微量的与水不相溶的有机溶剂作为分散剂,加入到水样中进行混合,形成的微小液滴,将样品中的SPAHs从水相中转移到有机溶液中,实现提取.

在使用DLLME方法处理样品过程中,可能出现乳液状液体,从而影响萃取效果,因此,在DLLME的基础上,使用去乳化剂将乳液状分散成微小液滴,从而发展出溶剂去乳化分散液液萃取(solvent de-emulsification dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction, SD-DLLME)技术. Guiñez等[22]通过使用SD-DLLME技术,对水样中的NPAHs和OPAHs进行提取,每个样品使用750 µL丙酮作为分散溶剂和500 µL二氯甲烷作为萃取溶剂,混合分散提取后,再向样品中加入1 mL甲醇作为脱乳化剂分解乳液,促进两相分离,获得提取SPAHs的二氯甲烷萃取溶液,该前处理方法的回收率在95.1%到98.5%之间. 比较而言,LLE对有机溶剂的使用量较大,通常具有较好的稳定性. DLLME的有机溶剂使用量小,更为经济环保,微小的液滴能够提供更大的比表面积,有利于提高目标物质的提取效率,但通常适用于低浓度物质的提取及富集.

固相萃取(solid-phase extraction, SPE)技术因其操作便捷、提取效率高、适用范围广等优点,在环境样品前处理过程中,得到广泛应用. 尤其在水样的前处理中,SPE处理技术可兼具化合物提取和样品净化的功能,简化样品前处理流程,节省人力和时间. 用于SPAHs分离富集的SPE技术主要基于固相材料对目标物质的选择性吸附,从而将其从样品中提取出来并富集在固相中,后再使用有机溶剂,将固相材料中的目标物质解吸洗脱,得到含有目标物质的溶液用于后续浓缩和分析. 因此,吸附剂的选择,决定了SPE技术对待测物质的提取效率. Liu等[19]使用SPE技术对饮用水样品中的16种PAHs、16种Cl-PAHs和10种Br-PAHs进行前处理,共选择了6种不同填料类型的SPE小柱进行萃取效率的评估,同时选择3种洗脱溶剂,包括二氯甲烷、正己烷、以及二氯甲烷∶正己烷(体积比1∶1)的混合溶液. 结果表明,LC18填料搭配二氯甲烷洗脱溶剂的提取效率最高,回收率范围为74.88%—119.4%,RSD为2.0%—18.7%. 固相萃取技术不局限于使用萃取小柱,Manousi等[18]合成了一种新型磁性纳米材料,将其添加到自来水、河水、矿物水样品中,在超声辅助下,对PAHs和NPAHs进行磁性固相萃取(magnetic solid-phase extraction, MSPE). 在SPE技术的基础上发展出来的固相微萃取(solid-phase microextraction, SPME)技术,也被应用于提取水体中的SPAHs. 该技术的主要特点是通常使用直径为微米级的纤维,对微量样品中的待测物质进行分离和富集,纤维表面的涂层直接影响提取效率. 有研究通过自合成新型聚合物,并将其作为SPME的纤维涂层,用于环境水样中PAHs、OPAHs、NPAHs的提取富集[24]. 除水样外,一些液体样品如咖啡和牛奶,其中SPAHs的提取富集方法多基于水样的前处理方法,一般使用SPE技术或基于该技术进行一些改进[28 − 29].

-

固体样品类型包括土壤、沉积物、颗粒物或灰尘、生物、固体食物等. 对于固体样品中SPAHs的提取和富集,常见的方法有索式萃取、超声辅助萃取、以及加压溶剂萃取等.

索氏萃取(Soxhlet extraction, SE)技术广泛应用于提取固体样品中的挥发性物质,在多环芳烃类化合物的提取和富集过程中较为常见. 该技术通过加热-冷却系统循环使用溶剂从而达到连续提取目标化合物的目的. Masuda等[35]使用SE技术,每个样品使用250 mL二氯甲烷作为提取溶剂,经过16 h的提取过程,从海洋沉积物和鱼类样品中提取富集了12种Br-PAHs,该方法加标回收率分别为51%—120%和68%—92%. 使用SE技术,以二氯甲烷∶正己烷(体积比3∶1)的混合溶液作为提取溶剂,经过16 h的提取过程,从碎纸机废物、室内灰尘、树叶及土壤样品种提取了20种Cl-PAHs[36]. SE技术对于设备要求不高,但一般耗时较长,影响前处理效率,且使用的溶剂量较大.

超声辅助萃取(ultrasound assisted extraction, USE)技术一般在超声辅助下,促进固体样品中的目标化合物快速迁移溶解到萃取溶剂中. 该技术的提取速度快且对温度和压力没有要求,操作简便. 已有研究使用USE技术对大气颗粒物和土壤样品中的Cl-PAHs、OPAHs、NPAHs进行提取富集,使用的萃取溶剂包括二氯甲烷∶甲醇(体积比3∶1)的混合溶液、二氯甲烷、正己烷[45,48]. 与SE技术相比,USE技术的提取速度虽然更快,但其通常经过多次重复,超声辅助萃取时间从几分钟到几十分钟不等,从而将固体样品中的目标化合物尽可能多的提取出来,这个过程对人力需求较大.

微波辅助萃取(microwave-assisted extraction, MAE)技术一般在加热条件下,利用微波辐射加速样品中化合物的萃取过程. MAE技术广泛应用于提取环境样品中的PAHs,相比之下,其在SPAHs的环境样品前处理应用较少. 有研究使用25 mL正己烷∶丙酮(体积比1∶1)的混合溶液作为萃取剂,升温程序为10 min内上升至110 ℃后继续保持10 min,对土壤和大气颗粒物样品中的NPAHs和OPAHs进行同时提取[49 − 50]. Tutino等[51]使用MAE对大气颗粒物样品中的NPAHs和PAHs进行同时提取,萃取溶剂为10 mL的正己烷∶丙酮(体积比1∶1)混合溶液,萃取条件为110 ℃持续10 min. MAE技术无需复杂的设备和较高的专业技能即可完成,在萃取速度方面具有优势.

从固体样品中提取化合物时经常用到加压溶剂萃取(accelerated solvent extraction, ASE)技术. 该技术的特点是在高温高压的环境下,提高萃取溶剂的渗透和扩散速率,从固体中快速溶解提取目标化合物,整个过程可自动化多次循环,提取效率高. 针对不同类型的待提取化合物,ASE方法可优化的参数包括,温度、压力、预热时间、循环次数、静置时间、冲洗体积、提取溶剂等. Ahmed等[47]使用ASE方法对灰尘及柴油颗粒物中的四种OPAHs进行提取,并对ASE的各个参数进行优化,结果表明改变参数对于不同类型OPAHs的提取效率改变存在差异,例如,将提取溶剂由甲苯∶甲醇(体积比9∶1)的混合溶液变成甲苯溶液,同时改变压力和预热时间后,提高了3种OPAHs的回收率,但同时降低了4H-cyclopenta[def]phenanthren-4-one(CCPQ)的回收率. 另一项研究从贻贝样品中提取6种OPAHs时也采用了ASE技术,其使用的洗脱溶剂为己烷∶丙酮(体积比3∶1)的混合溶液,得到的回收率范围为41%—93%[38]. 对于ASE技术,提取溶剂仍然是影响其前处理回收率的重要参数. 此外,一项关于食物中OPAHs的研究,也使用了ASE技术进行前处理[39].

-

利用大气采样器收集样品时,一般分为气体样品和颗粒物(particulate matter, PM)样品,颗粒物样品一般被截留在滤膜上,而气体样品中的污染物一般通过固体材料吸附进行收集,如聚酯泡沫(polyurethane foam, PUF). 吸附到固体材料中的气体污染物,随后通过ASE或SE技术进行提取和富集. Jin等[46]通过ASE技术,使用己烷∶二氯甲烷(体积比1∶1)的混合溶液,从大气样品中提取了38种Cl-PAHs和Br-PAHs,平均回收率在65.7%—110%. Vuong等[44]使用正己烷和丙酮的混合溶液,通过SE技术提取了大气样品中的24种Cl-PAHs和11种Br-PAHs.

-

净化过程一般发生在提取步骤之后,或与提取过程同步进行. 根据环境样品基质的复杂情况以及提取技术的不同,提取液中除了包含目标化合物外还可能有部分杂质,其可能干扰分析结果,降低分析的灵敏度和准确性. 此时,一般会加入净化步骤,进一步去除提取液中的干扰杂质. 在针对SPAHs的样品前处理中,通常单独或联合使用SPE、凝胶渗透色谱(gel permeation chromatography, GPC)以及硅胶柱色谱对提取溶液进行净化处理. GPC技术多用于去除样品基质中的脂类、蛋白质、硫和其他的高分子化合物. Sankoda等[33]为分析河流沉积物等固体样品中的Cl-PAHs,在样品前处理过程中,联合使用活性硅胶柱和GPC方法对经过USE和SPE得到的萃取溶液进行净化. Horii等[41]利用活性硅胶柱,以正己烷为流动相,净化索氏萃取所得的溶液,用以分析Cl-PAHs. 更多应用详见表1.

-

环境样品中的SPAHs赋存浓度一般较低,且样品基质干扰较大,对分析灵敏度要求较高. 目前主流的分析检测方法仍为质谱法,其前端联用的分离方法有气相色谱和液相色谱,其中气相色谱应用相对更多. 当同时分析多种SPAHs物质时,一般需要在色谱部分调节参数,实现目标化合物的相对分离,同时辅助提高分析的灵敏度和准确性. 所采用的分析策略通常分为目标分析和疑似/非靶标分析.

目标分析通常指明确样品中将要分析的目标化合物,且有对应的标准品,能够得到目标待测物的确切保留时间和质谱信息,用于比对确认分析结果,并进行准确定量. 对于传统的、已有大量研究基础的、有高纯度标准品的多环芳烃类化合物,通常使用目标分析策略和普通分辨率的质谱即可达到分析目的. 表1中列出了目标分析目的下不同环境样品中四类SPAHs的分析方法. 通过表1可知,四类SPAHs的分析仪器一般为气相色谱-质谱(gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, GC-MS)或气相色谱-串联质谱(gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry, GC-MS/MS),离子源通常使用电子轰击源(electron ionization, EI). 化学电离源(chemical ionization, CI)、大气压化学电离源(atmospheric pressure chemical ionization, APCI)和大气压光学电离源(atmospheric pressure photo ionization, APPI)虽也有应用,但不是分析SPAHs类化合物的普遍离子源. 分析方法的检出限通常可达到pg级别,检出限的波动与样品基质干扰有关. 前处理方法对环境样品的净化效果越好,越有利于去除基质干扰,一定程度上帮助提高检出限. 需要注意的是,样品净化并非越干净越好,过度净化可能造成目标化合物的损失,从而不利于检出.

近年来,基于高分辨质谱的疑似/非靶标分析策略发展迅速,通常被用于发现环境中的未知污染物. 该策略简而言之,即不预设具体目标化合物的前提下,利用先验信息或独立预测的方式对样品中质谱可检测到的化合物进行全面分析. 该技术目前已应用于环境样品中未知多环芳烃类化合物的分析. 有研究使用Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance(FT-ICR)高分辨质谱技术,利用非靶标分析策略,识别了大气颗粒物中多种高分子量的多环芳烃类化合物,其中就包括烷基化及含杂原子的多环芳烃,后通过comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography-time-of-flight(GC×GC-TOF)高分辨质谱对上述化合物进行结构鉴定,最终识别确定了300多种多环芳烃类物质[52]. 由此可见,基于高分辨质谱的非靶标/疑似靶标分析策略相较于传统的色谱质谱目标分析方法,具有更高的分析通量. 需要注意的是,疑似/非靶标分析策略下识别出来的未知化合物或污染物,可能由于缺少高纯度标准品而难以准确鉴定和定量,这使其在污染物的环境分布特征研究方面存在一定限制.

-

相比于其他环境介质,大气颗粒物中SPAHs的研究报道相对较多,其浓度水平一般与其母体PAHs浓度水平相当或更低. 对中国南方两个工业场地的PM2.5样品的分析结果表明,其中NPAHs和OPAHs的浓度比其母体PAHs低约2—3个数量级[53]. 表2总结了近十年全球不同地区大气气相和颗粒物中四类SPAHs的浓度水平,其中浓度是指某类SPAHs中多种化合物的总浓度,因此浓度值高低与所检测的目标化合物个数多少有关. 总体而言,NPAHs和OPAHs的大气分布水平比Cl-PAHs和Br-PAHs高,OPAHs和NPAHs在大气中的浓度水平最高分别可达数百和数十ng·m−3;Cl-PAHs和Br-PAHs的大气浓度分布在pg·m−3水平上. 比较同一报道中Cl-PAHs和Br-PAHs在PM2.5和PM10中的分布水平可知,这两种取代多环芳烃在颗粒物上的吸附量与颗粒物粒径之间不存在明确的相关关系[66 − 67]. 大气中四种类型的SPAHs浓度分布呈现一致的季节变化特点,即冬季高于夏季. 一项针对中国深圳大气颗粒物中Cl-PAHs和Br-PAHs的研究[67],以及一项针对韩国首尔大气中OPAHs的研究[64]均表明,取代多环芳烃总量均表现出冬季 > 秋季 > 春季 > 夏季的季节变化特征.

四类取代多环芳烃在大气中均表现出冬季高于夏季的特征,可能由于供暖以及冬季环境条件有利于对这些化合物在大气颗粒中富集[54,70]. 与夏季相比,冬季的供暖增加,光化学反应和热降解反应相对较弱. 有研究表明,生物质燃烧(如住宅供暖)与大气中OPAHs和NPAHs的浓度有关[59]. 针对我国大气颗粒物中OPAHs的十年监测数据显示,其浓度水平在冬季出现明显下降,这与我国减少煤炭消耗量,而采用石油和天然气进行替代有很大关系[63]. Ohura等[71]对日本静岗市大气颗粒物中的取代多环芳烃1-氯芘(1-ClPyr)进行监测发现,其在夏季的浓度为2.4 pg·m−3,冬季浓度为18.9 pg·m−3,原因是冬季低温不利于1-ClPyr从颗粒物中挥发,且弱光照会降低1-ClPyr的光解速率,利于其在颗粒物中富集. 取代多环芳烃除了来自PAHs的转化,也可直接来自人类排放. 如大气中的NPAHs和Cl-PAHs可能来源于柴油或汽油燃烧和汽车尾气排放[72 − 73]. 排放到大气中或在大气中产生的SPAHs可以通过土壤/植被-空气交换或干湿沉降沉积到土壤、水体和植被表面上. 大气沉降是城市地表土、植被和水环境中SPAHs的重要来源.

-

关于取代多环芳烃分布的报道多集中在表层土壤,目前已在城市、工业园区、农业用地、森林的表层土壤中检出四类SPAHs(表3),其中,关于Cl-PAHs的研究相对较少,且其在表层土壤中的分布水平相较于其他三类取代多环芳烃相对更低. 土壤中的SPAHs分布水平与人类活动密切相关,人类活动越密集的区域,土壤中SPAHs的浓度水平可能更高. 例如,青藏高原地区表层土壤中Cl-PAHs和Br-PAHs的总浓度范围分别为0.003—0.297 ng·g−1和

0.0006 —0.0723 ng·g−1[68],比表3中其他地区表层土壤中的对应浓度低至少一个数量级. 在人类活动较少的森林区域表层土壤中,OPAHs的总浓度范围在3—39 ng·g−1 [79],而在另一项研究中,位于铝厂附近的森林区表层土中,OPAHs的总浓度范围高达430—2900 ng·g−1 [80]. 不同土地利用类型的表层土壤中取代多环芳烃的分布水平也存在差异.例如,在我国浙江一农业区、电子废物回收厂、化学工业园区采集的表层土壤样品中,12种Cl-PAHs的总浓度平均值分别为0.15、26.8、88.0 ng·g−1 [36],即工业园区土壤中的分布水平相对更高. 另一项在越南兴安针对3种土地利用类型的表层土壤中Br-PAHs的研究也表明,相比于电子废物回收厂和露天燃烧区土壤,稻田表层土壤中10种Br-PAHs的分布水平最低[82]. 表层土壤中的取代多环芳烃污染物可能被植被吸收,在根部积累随后在植物内迁移到不同位置.

-

在自然水体的水相和颗粒物/沉积物中,均有检出四类SPAHs(见表4). 在采集自海河的样品中,未在水体中检出NPAHs,在水体颗粒物样品中检出的OPAHs浓度水平(410—

17980 ng·g−1)远高于水体样品(60—190 ng·L−1)[88]. 而另一项在太滆运河开展的研究,在水体和沉积物中都检出了NPAHs,且最大总浓度和总浓度平均值均表现出水体高于沉积物[89]. 关于环境样品中某类取代多环芳烃是否被检出,除了样品采集地可能没有该类化合物的污染外,可能与所选择的某类取代多环芳烃的化合物类型有关. 例如上述关于海河的研究中,仅选择了5种NPAHs,而太滆运河的研究中选择了15种NPAHs,选择化合物类型增多,可能也增加了该类化合物被检出的可能性. 水体沉积物中取代多环芳烃的分布水平变化与季节也有一定关联. 例如在不同季节采集松花江的沉积物样品中,NPAHs和OPAHs的浓度水平均体现出了旱季高于雨季[91]. 除了NPAHs和OPAHs外,在自然水体的沉积物中还检出了Cl-PAHs和Br-PAHs类化合物.污水处理厂入水、出水和活性污泥样品中,均检测到OPAHs,且整体上出水样品的浓度水平(70—109 ng·L−1)低于入水样品的浓度水平(139—155 ng·L−1),而在活性污泥样品中检出的浓度水平最高(695—

1533 ng·g−1),表明污水处理厂对污水中OPAHs化合物可以进行一定程度的净化,且OPAHs更多在活性污泥中富集[84]. 此外,在污水处理厂出水中还检测到了Cl-PAHs和Br-PAHs[85 − 86]. 这些研究结果提示了污水处理厂出水排放和活性污泥的环境处置都可能带来包括OPAHs、Cl-PAHs、Br-PAHs的取代多环芳烃的二次环境污染,可能是自然水体中这些污染物的重要来源. -

除了大气、水体、土壤的自然环境外,在道路灰尘、植物和食物中均有SPAHs检出,具体如表5所示. 在城市道路灰尘样品中检出的NPAHs(885 ng·g−1)和OPAHs(

4754 ng·g−1),其浓度水平比表层土壤的浓度水平高,其中的OPAHs更多的是来自于燃烧活动排放后的大气沉降,而NPAHs除了来自于沉降外,还来自于汽车尾气的排放[74]. 在树叶、树皮和碎纸机废止中也有OPAHs和Cl-PAHs的分析报道,其浓度普遍可达到数十ng·g−1的水平(表5).有研究在蔬菜和水生生物中检出了Cl-PAHs和Br-PAHs,说明这些污染物已经进入食物链,很可能沿着食物链传递和累积. 王丽等[37]对北京市售菠菜及萝卜样品中的11种Cl-PAHs和Br-PAHs进行分析,结果表明其中9种化合物在所有蔬菜样品中均有检出,该研究首次在蔬菜中检测到了这两类卤代多环芳烃化合物. 在我国华南沿海城市海鲜市场采集的螃蟹、虾、贝壳的海鲜样品中,检测到Cl-PAHs和Br-PAHs的总浓度最大分别达到2.44、6.73、4.76 ng·g−1[95],证明了这些氯代和溴代多环芳烃能够通过食物供给暴露于人体. 此外,经过烧烤烹饪后,在熟食牛肉饼和素食饼中,检出了OPAHs的浓度分别高达62.4 ng·g−1和14.4 ng·g−1[39]. 有研究已经证明了SPAHs的生物毒性作用,有些Cl-PAHs甚至比其母体PAHs显示出了更高的毒性效应,例如Cl-PAHs通过与芳烃受体结合并激活,能够引发MCF-7细胞中细胞色素P450 1A1的表达,导致DNA受损[98]. 这些具有生物毒性作用的SPAHs,在食物链和烹饪熟食中赋存,最终通过食物供给经口暴露于人体,因此带来的潜在健康风险不容忽视.

-

通过总结现有研究可知,目前已在各种环境介质、食物链、食品中检测到了取代多环芳烃,表明其已在环境中广泛分布,对生态环境和人体造成了不同浓度水平、不同时间尺度、多个维度的全面暴露. 在所有介质中,针对大气环境的研究报道明显更多,这可能主要是考虑到燃烧排放是多环芳烃类化合物的重要来源,而对于可对人体产生经口暴露的食物链或食物中的报道相对较少. 针对取代多环芳烃的分析方法,目前仍然以基于GC-MS或GC-MS/MS技术的已知化合物靶标分析为主,不同研究报道的浓度水平通常与所选择的目标化合物类型和个数密切相关,研究之间的可比性较差,且对于具有生物毒性作用的卤代多环芳烃的研究较少,传统的靶标分析对于环境生物转化产物或新的未知多环芳烃衍生物的研究存在很大局限.

在未来的研究中,应该加强对于多环芳烃衍生物在水体、土壤、大气等环境中的迁移、转化、归趋、生物暴露、健康风险的相关研究. 作为研究基础,需要进一步完善SPAHs的分析方法,简化不同基质中SPAHs的前处理方法,提高样品中SPAHs的分析通量,标准化重要SPAHs的检测流程,促进该类化合物的多介质、多尺度、多暴露场景的常规监测和大数据分析. 发展高分辨质谱的非靶标分析方法,在已知SPAHs的先验分析方法基础上,利用高分辨质谱和多种数据分析策略发现潜在未知多环芳烃类化合物,为深入研究其环境转化行为及机制提供方法支撑. 需加强对多环芳烃衍生物的真实暴露场景和暴露水平的研究工作,基于此进一步开展其生物毒理学研究,并评估其在真实暴露条件下的健康风险,从而明确对人体健康具有潜在危害的重点关注化合物,并将其纳入污染监管和防控.

环境中多环芳烃衍生物的检测方法及污染现状

Detection methods and pollution status of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons derivatives in the environment

-

摘要: 取代多环芳烃(substituted polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons,SPAHs)是一类重要的多环芳烃衍生物,一般来自人类活动的直接排放以及多环芳烃的环境转化,因具有生物毒性作用而愈加受到关注. 作为高风险新型污染物,SPAHs环境暴露引起的潜在健康危害不容忽视. 掌握SPAHs的检测方法以及在不同环境中的赋存现状,将为进一步开展该类化合物的全面环境监测和人体暴露风险评估提供重要依据. 本文基于国内外研究报道,总结了氧化多环芳烃、硝基多环芳烃、氯代多环芳烃以及溴代多环芳烃四类SPAHs在不同基质中的前处理方法以及分析方法,讨论了其在多种环境、生物、食物中的赋存水平和分布特征,并基于研究现状对其未来的研究趋势进行了展望.Abstract: Substituted polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (SPAHs) are an important class of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) derivatives, which are generally derived from direct emissions from human activities and environmental transformation of PAHs. SPAHs are of increasing concern due to their biotoxicity, and the potential health hazards caused by environmental exposure to them should not be ignored. Understanding the detection methods and the environmental distribution of SPAHs will support comprehensive environmental monitoring, and the risk assessment of human exposure to these compounds. Based on domestic and international research reports, we have here summarized the pretreatment methods and analytical methods of four types of SPAHs, including oxygenated PAHs, nitrated PAHs, chlorinated PAHs, and brominated PAHs, in different matrices, discussed their distribution characteristics in different environments, organisms, and foods, and provided an outlook on the future research trends given the current research status.

-

-

表 1 环境样品中四类SPAHs的前处理及分析方法

Table 1. Pretreatment and analytical methods for four types of SPAHs in environmental samples

环境介质

Environmental matrix样品类型

Sample typeSPAHs类型

SPAHs type前处理方法

Pretreatment method分析方法

Analytical method检出限

Limit of detection回收率/%

Recovery参考文献

Reference提取方法

Extraction净化方法

Purification液体样品

Liquid sample矿泉水

Mineral waterNPAHs MSPE GC-EI-MS 0.01—0.11 ng·mL−1 91.6—108.8 [18] 饮用水

Drinking waterCl-PAHs SPE GC-EI-MS 0.10—0.50 ng·mL−1 74.88—119.4 [19] Br-PAHs 0.25—0.50 ng·mL−1 饮用水

Drinking waterNPAHs SPME GC-NCI-MS 0.10—20.0 ng·L−1 81.2—113 [20] 自来水

Tap waterNPAHs MSPE GC-EI-MS 0.01—0.11 ng·mL−1 93.6—108 [18] 自来水

Tap waterCl-PAHs SPE GC-EI-MS 0.015—0.591 ng·L−1 82.5—102.6 [21] 饮用水、河水

Drinking water and river waterNPAHs SD-DLLME UHPLC-APCI-MS/MS 11.2—89.0 ng·L−1 95.1—98.5 [22] OPAHs 8.90—81.9 ng·L−1 95.7—98.3 饮用水、湖水

Drinking water and lake waterNPAHs DLLME UHPLC-APCI-MS/MS 0.05—0.85 ng·mL−1 94.5—99.6 [23] OPAHs 0.02—0.17 ng·mL−1 94.9—100.4 自来水、河水、湖水

Tap water, river water and lake waterOPAHs SPME GC-EI-MS 2.50—12.0 ng·L−1 73.1—118.3 [24] NPAHs 6.00—16.5 ng·L−1 河水

River waterNPAHs SPE、LLE HPLC-CL 0.01—0.15 nmol·L−1 70.0—103 [25] 河水

River waterNPAHs MSPE GC-EI-MS 0.01—0.11 ng·mL−1 92.3—110.3 [18] 地下水

GroundwaterOPAHs LLE GC-EI-MS 0.30—360 ng·L−1 — [26] 地下水

GroundwaterOPAHs、NPACs、Cl-PAHs LLE GC-EI-MS 1.70—8.80 ng·L−1 54.3—115.1 [27] 乳制品

Dairy productsCl-PAHs SPE GC-EI-QQQ-MS 0.11 μg·kg−1 87.16—100.98 [28] OPAHs 0.08—0.12 μg·kg−1 101.15—109.17 咖啡

CoffeeOPAHs SPME GC-EI-MS 0.031—0.048 μg·L−1 88.2—95.3 [29] NPAHs 0.051—0.059 μg·L−1 82.2—94.6 固体、

大气样品

Solid and atmospheric sample土壤

SoilCl-PAHs SE 硅胶柱、双层碳柱 GC-EI-QQQ-MS/MS 0.60—3.60 pg 70.0—117 [30] 土壤

SoilBr-PAHs SE 硅胶柱、双层碳柱 GC-EI-QQQ-MS/MS 0.4—5.0 pg 71.0—118 [30] 土壤

SoilOPAHs USE SPE GC-EI-MS 0.001—0.059 μg·mL−1 82.0—90.0 [31] 土壤

SoilPAHs、Br-PAHs、Cl-PAHs ASE 活性氧化铝柱 GC×GC-TOF — 60.0—94.0 [32] 土壤

SoilNPAHs SPME GC-NCI-MS 0.10—20.0 ng·L−1 69.6—119.2 [20] 河流沉积物

River sedimentCl-PAHs USE+LLE 硅胶柱、GPC GC-EI-MS 1.70—21.3 pg·g−1 27.0—86.0 [33] 河流沉积物

River sedimentCl-PAHs SE 硅胶柱 GC-EI-MS — 105.3—157.6 [34] 河流沉积物

River sedimentBr-PAHs SE 硅胶柱 LC-APPI-MS/MS 0.09—1.1 pg·g−1(定量限,Limit of quantitation) 51.0—120 [35] 电子废物、灰尘、植被、土壤

Electronic waste, dust, vegetation and soilCl-PAHs SE 硅胶柱 GC-EI-MS 0.06—0.36 ng·g−1(定量限,Limit of quantitation) — [36] 蔬菜

VegetablePAHs、Br-PAHs、Cl-PAHs DSPE SPE GC-EI-MS/MS 0.03—7.39 μg·kg−1 74.7—115.1 [37] 贻贝

MusselOPAHs ASE 二氧化硅 HPLC-APCI-MS 0.08—3.57 ng·g−1 41.0—93.0 [38] 鱼

FishBr-PAHs SE 硅胶柱 LC-APPI-MS/MS 0.2—2.6 pg·g−1(定量限,Limit of quantitation) 68.0—92.0 [35] 牛肉饼、素食饼

Beef patty and vegetarian pattyOPAHs ASE SPE GC-EI-HRMS 0.04—0.43 μg·kg−1 74.0—106 [39] 室内灰尘

Indoor dustCl-PAHs SPE GC-EI-MS/MS 2.00—40.0 pg·g−1 — [40] Br-PAHs 2.00—20.0 pg·g−1 垃圾焚烧炉飞灰、底灰

Fly ash and bottom ash of waste incineratorCl-PAHs SE 硅胶柱 GC-EI-MS 0.06—0.14 ng·g−1 93.0—120 [41] PM2.5 Br-PAHs ASE 硅胶柱 GC-EI-MS 0.12—0.58 pg·m−3 68.9—111.5 [42] PM2.5 NPAHs SPME GC-NCI-MS 0.10—20.0 ng·L−1 62.4—119.4 [20] PM2.5 OPAHs USE GC-EI-MS 4.20—8.30 pg·m−3 — [43] NPAHs LC-APCI-MS 10.0—83.0 pg·m−3 固体、

大气样品

Solid and atmospheric sample大气气相、TSP

Atmospheric gas phase and TSPCl-PAHs SE GC-EI-MS 0.08—5.46 pg·m−3 — [44] 大气气相、TSP

Atmospheric gas phase and TSPBr-PAHs 0.32—2.28 pg·m−3 TSP Cl-PAHs USE 硅胶柱 GC-EI-HRMS 0.05—0.39 pg·m−3 91.0—472 [45] 大气气相、TSP、垃圾焚烧炉烟气

Atmospheric gas phase, TSP and waste incinerator smokeCl-PAHs ASE、SE 硅胶柱、活性炭柱、GPC GC-EI-HRMS 0.20—1.80 pg 71.7—110 [46] Br-PAHs 0.70—2.70 pg 65.7—99.7 TSP、柴油颗粒物

TSP and diesel particulate matterOPAHs ASE SPE LC-GC/MS 0.20—0.80 pg 67.0—110 [47] TSP OPAHs USE GC-EI-MS 15.0—269 pg 75.0—116 [48] TSP:总悬浮颗粒物,total suspended particles;SPE:固相萃取,solid-phase extraction;MSPE:磁性固相萃取,magnetic solid-phase extraction;SPME:固相微萃取,solid-phase microextraction;DSPE:分散固相萃取,dispersive solid-phase extraction;LLE:液液萃取,liquid-liquid extraction;SD-DLLME:溶剂去乳化分散液液萃取,solvent de-emulsification dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction;ASE:加压溶剂萃取,accelerated solvent extraction;USE:超声辅助萃取,ultrasound assisted extraction;SE:索式萃取,Soxhlet extraction;GPC:凝胶渗透色谱,gel permeation chromatography;GC:气相色谱,gas chromatography;LC:液相色谱,liquid chromatography;HPLC:高效液相色谱,high performance liquid chromatography;UHPLC:超高效液相色谱,ultra-high performance liquid chromatography;EI:电子轰击源,electron ionization;NCI:负化学电离源,negative chemical ionization;APCI:大气压化学电离源,atmospheric pressure chemical ionization;APPI:大气压光学电离源,atmospheric pressure photo ionization;MS:质谱,mass spectrometry;MS/MS:串联质谱,tandem mass spectrometry;CL:化学发光法,chemiluminescence;QQQ:三重四极杆,triple quadrupole;TOF:飞行时间质谱,time of flight mass spectrometer;HRMS:高分辨质谱,high-resolution mass spectrometry;—:未提供,not provided. 表 2 不同地区大气样品中四类SPAHs的浓度

Table 2. Concentrations of four types of SPAHs in atmospheric samples from different regions

SPAHs类型

SPAHs type采样地点

Sampling area样品类型

Sample type浓度

Concentration参考文献

ReferenceNPAHs 中国

China西安

Xi’anPM2.5 0.30—2.5a(夏季),1.5—7.0a(冬季) [54] PM2.5 0.079b(室内),0.10b(室外) [55] 上海(徐家汇)

Shanghai (Xujiahui)PM2.5 0.653b(1月),0.246b(4、5月),0.118b(7月),0.285b(10、11月) [56] 上海(宝山)

Shanghai (Baoshan)PM2.5 0.796b(1月),0.302b(4、5月),0.155b(7月),0.52b(10、11月) [56] 西班牙

Spain马德里

MadridPM10 0.132b [57] 葡萄牙

Portugal波尔图

PortoPM2.5 9.15b(夏季),15.8b(冬季) [58] 意大利

Italy佛罗伦萨

FlorencePM2.5 3.36b(夏季)—10.9b(冬季) [58] 希腊

Greece雅典

AthensPM2.5 2.73b(夏季)—15.9b(冬季) [58] 巴西

Brazil阿拉拉夸拉

Araraquara气溶胶 0.16—7.7a [59] 贝洛奥里宗特

Belo HorizontePM2.5 1.00b [60] 气相 0.83b NPAHs 泰国

Thailand清迈

ChiengmaiTSP 0.523b(2月),0.192b,(3月)0.072b(4月),0.037b(5月),0.025b(8月),0.041b(9月) [61] OPAHs 中国

China北京

BeijingPM2.5 84.7b [62] 天津

TianjinPM2.5 96.17b [62] 石家庄

ShijiazhuangPM2.5 180b [62] 衡水

HengshuiPM2.5 121b [62] 西安

Xi’anPM2.5 16.4b(室内),19.1b(室外) [62] PM2.5 5—40a(夏季),29—208a(冬季) [54] 气溶胶 29b (5.4—79)a(夏季),54b (35—70)a(冬季) [63] 广州

Guangzhou气溶胶 11b (2.8—29)a(夏季),23b (2.7—80)a(冬季) [63] 韩国

Korea首尔

SeoulPM10 4.22b(春季),1.47b(夏季),

4.28b(秋季),8.70b(冬季)[64] 西班牙

Spain马德里

MadridPM10 0.083b [57] 葡萄牙

Portugal波尔图

PortoPM2.5 19b(夏季)—41.8b(冬季) [58] 意大利

Italy佛罗伦萨

FlorencePM2.5 3.1b(夏季)—11b(冬季) [58] 希腊

Greece雅典

AthensPM2.5 0.704b(夏季)—12.6b(冬季) [58] 巴西

Brazil阿拉拉夸拉

Araraquara气溶胶 0.69—6.0a [59] 贝洛奥里宗特

Belo HorizontePM2.5 1.62b [60] 气相 0.86b Cl-PAHs 中国

China北京

Beijing气相+TSP 60.38—482.17a [65] TSP 12.76b(夏季),211.6b(冬季) [45] 上海

ShanghaiPM2.5 12.3b (2.45—47.7)a [66] PM10 9.06b (1.34—22.3)a [66] 深圳

ShenzhenPM2.5 39.7b [67] PM10 45.8b 青藏高原

Tibet PlateauTSP 0.78—4.16a [68] 日本

Japan札幌

SapporoTSP 1.28b(夏季),8.51b(冬季) [45] 相模原

SagamiharaTSP 1.54b(夏季),8.43b(冬季) [45] 金泽

KanazawaTSP 0.76b(夏季),3.29b(冬季) [45] 北九州

KitakyushuTSP 1.38b(夏季),14.3b(冬季) [45] — TSP 15.2b [16] 名古屋

NagoyaTSP 43.3—92.6b [69] 韩国

Korea釜山

BusanTSP 1.17b(夏季),14.2b(冬季) [45] 蔚山广域市

Ulsan gwangyeoksi气相 8.64b [44] TSP 9.64b [44] Br-PAHs 中国

China北京

Beijing气相+TSP 1.32—25.35a [65] 深圳

ShenzhenPM2.5 150b [67] PM10 350b 青藏高原

Tibet PlateauTSP 0.15—0.59a [68] 日本

Japan— TSP 8.6b [16] 韩国

Korea蔚山广域市

Ulsan gwangyeoksi气相 11.6b [44] TSP 1.62b [44] a: 多种SPAHs的总浓度;b: 总浓度平均值;TSP:总悬浮颗粒物;NPAHs和OPAHs浓度单位为ng·m−3;Cl-PAHs和Br-PAHs浓度单位为pg·m−3;—:未提供.

a: total concentrations of multiple SPAHs; b: average values of total concentrations; TSP:total suspended particles; the concentration units of NPAHs and OPAHs are ng·m−3; the concentration units of Cl-PAHs and Br-PAHs are pg·m−3; —: not provided.表 3 表层土壤样品中四类SPAHs的浓度

Table 3. Concentrations of four types of SPAHs in surface soil samples

SPAHs类型

SPAHs type采样地点

Sampling area样品来源

Sample source浓度/( ng·g−1)

Concentration参考文献

ReferenceNPAHs 中国

China西安

Xi’an城郊 854b [74] 长江三角洲

Yangtze River delta— 0.6b (0.4—4.6)a [75] 农业区 14.4-85.5a [76] 东部26个省

26 provinces in the east农业区 50b [49] 瑞士

Switzerland巴塞尔

Basel— 0.03—0.80a [77] 越南

Vietnam河内

Hanoi交通站点 0.112—0.780a [78] OPAHs 中国

China西安

Xi’an城郊 118b [74] 东部26省

26 provinces in the east农业区 9b [49] 长江三角洲

Yangtze River delta— 36.3b (2.1—834.1)a [75] 美国

America佛罗里达州

Florida State森林 6b [79] 3b 华盛顿州

Washington State森林 39b [79] 11b 泰国

Thailand曼谷

Bangkok城区 12—269a [70] 斯洛伐克

Slovakia中部地区

Middle region铝厂附近森林 430— 2900 a[80] Cl-PAHs 中国

China青藏高原

Tibet Plateau— 0.003—0.297a [68] 浙江

Zhejiang province电子废物回收厂 26.8b (ND—96.4)a [36] 化学工业园区 88.0b (13.2—278)a 农业区 0.15b (ND—0.76)a 上海

Shanghai钢铁厂附近 0.05—94.3a [81] 越南

VietnamBui Dau 稻田 0.0254 —0.411a[82] 电子废物回收厂 0.0639 —2.17a露天燃烧区 0.192—2.44a 加纳

Ghana阿克拉

Accra电子废物回收厂 160—220a [83] Br-PAHs 中国

China青藏高原

Tibet Plateau— 0.0006 —0.0723 a[68] 越南

VietnamBui Dau 稻田 ˂LOQ—0.09a [82] 电子废物回收厂 0.002—0.402a 露天燃烧区 0.008—1.52a 加纳

Ghana阿克拉

Accra电子废物回收厂 19—46a [83] a: 多种SPAHs的总浓度;b: 总浓度平均值;LOQ: 定量限;ND: 未检出;—:未提供.

a: total concentrations of multiple SPAHs; b: average values of total concentrations; —: not provided.表 4 水体环境中四类SPAHs的分布水平

Table 4. Distribution levels of four types of SPAHs in the aquatic environment

采样地点

Area样品类型

Sample typeSPAHs类型

SPAHs type浓度

Concentration参考文献

Reference污水处理厂(北京)

Wastewater treatment plant (Beijing)入水

InfluentNPAHs ND [84] OPAHs 139—155a 出水

EffluentNPAHs ND OPAHs 70—109a 活性污泥

Activated sludgeNPAHs ND OPAHs 695— 1533 a出水

EffluentOPAHs 15.47—106.92a [85] Cl-PAHs ND—5.70a Br-PAHs ND—13.11a 出水

EffluentOPAHs 36—157a [86] Cl-PAHs 17—23a 潮白河

Chaobai River水体

WaterOPAHs 321b (49— 4659 )a[87] Cl-PAHs 30b (7—66)a 海河

Hai River水体

WaterNPAHs ND [88] OPAHs 60—190a 水体颗粒物

Particulate matterOPAHs 410— 17980 a太滆运河

Taigehe Canal水体

WaterNPAHs 120b (14.7—235)a [89] 沉积物

Sediment53.3b (22.9—96.5)a 珠江口

Pearl River Estuary沉积物

SedimentCl-PAHs 0.57—25.71a [90] Br-PAHs 0.84—15.16a [90] 松花江

Songhua River沉积物

SedimentNPAHs 12.2b(雨季)

36.9b(旱季)[91] OPAHs 2.54b(雨季)

9.87b(旱季)[91] 长江

Yangtze River水体

WaterOPAHs 7.7—90.4a [92] 伊朗波斯湾

Persian Gulf, Iran沉积物

SedimentOPAHs 15.2—172.7a [93] a: 多种SPAHs的总浓度;b: 总浓度平均值;水样的浓度单位为ng·L−1;污泥/颗粒物/沉积物的浓度单位为ng·g−1;ND: 未检出.

a: total concentrations of multiple SPAHs; b: average values of total concentrations; the concentration units of water samples are ng·L−1; the concentration units of sludge, particulate matters, and sediment samples are ng·g−1; ND: not detected.表 5 其他基质中四类SPAHs的分布水平

Table 5. Distribution levels of four types of SPAHs in other matrices

样品类型

Sample type样品来源

Sample sourceSPAHs类型

SPAHs type浓度 /(ng·g−1)

Concentration参考文献

Reference道路灰尘

Road dust城市道路(中国西安) NPAHs 885b [74] OPAHs 4754 b[74] 树皮

Bark城市(阿根廷布宜诺斯

艾利斯)NPAHs ND [94] OPAHs 180—720a [94] 树叶

Leaves电子废物回收厂内 Cl-PAHs 87.5b (46.0—111)a [36,95] 废纸

Waste paper碎纸机内 Cl-PAHs 59.1b (32.3—101)a [36] 蔬菜

Vegetable菠菜 Cl-PAHs+Br-PAHs 15.8b [37] 萝卜 14.7b [37] 叶菜 Cl-PAHs+Br-PAHs 0.620—0.874b [96] 根菜 0.357—0.650b [96] 水生生物

Aquatic organism花鲈鱼 Br-PAHs ˂LOQ [35] 黄盖鲽鱼 Br-PAHs [35] 螃蟹 Cl-PAHs+Br-PAHs 1.35b (0.81—2.44)a [95] 虾 Cl-PAHs+Br-PAHs 1.58b (0.81—6.73)a [95] 贝壳 Cl-PAHs+Br-PAHs 1.39b (0.79—4.76)a [95] 浅海生物 Cl-PAHs 2.58—27.1a [97] Br-PAHs 0.30—9.53a 沿海及河口生物 Cl-PAHs 3.87—56.5a Br-PAHs 0.44—8.51a 海洋生物 Cl-PAHs 0.35—18.3a Br-PAHs 0.03—3.34a 食物

Food牛肉饼 OPAHs 26.0—62.4a [39] 素食饼 OPAHs 5.7—14.4a [39] a: 多种SPAHs的总浓度;b: 总浓度平均值;LOQ: 定量限;ND: 未检出.

a: total concentrations of multiple SPAHs; b: average values of total concentrations; LOQ: limit of quantitation; ND: not detected. -

[1] ABDEL-SHAFY H I, MANSOUR M S M. A review on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Source, environmental impact, effect on human health and remediation[J]. Egyptian Journal of Petroleum, 2016, 25(1): 107-123. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpe.2015.03.011 [2] SHEN H Z, HUANG Y, WANG R, et al. Global atmospheric emissions of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from 1960 to 2008 and future predictions[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2013, 47(12): 6415-6424. [3] MINERO C, MAURINO V, BORGHESI D, et al. An overview of possible processes able to account for the occurrence of nitro-PAHs in Antarctic particulate matter[J]. Microchemical Journal, 2010, 96(2): 213-217. doi: 10.1016/j.microc.2009.07.013 [4] 马静, 吴明红, 徐刚, 等. 结构-活性关系对氯代多环芳烃性质的预测[J]. 上海大学学报(自然科学版), 2010, 16(5): 536-540. MA J, WU M H, XU G, et al. Physical/chemical property estimation for Cl-PAHs congeners by quantitative structure-activity relationship[J]. Journal of Shanghai University (Natural Science Edition), 2010, 16(5): 536-540 (in Chinese).

[5] ZHAO J, TIAN W J, LIU S H, et al. Fate of parent and substituted polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in SBR/MBBR treatment process: Experimental value against model prediction[J]. Journal of Ocean University of China, 2023, 22(2): 479-489. doi: 10.1007/s11802-023-5277-2 [6] HUANG L, CHERNYAK S M, BATTERMAN S A. PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons), nitro-PAHs, and hopane and sterane biomarkers in sediments of southern Lake Michigan, USA[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2014, 487: 173-186. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.03.131 [7] HONG W J, JIA H L, LI Y F, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and alkylated PAHs in the coastal seawater, surface sediment and oyster from Dalian, Northeast China[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2016, 128: 11-20. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.02.003 [8] GOLZADEH N, BARST B D, BAKER J M, et al. Alkylated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are the largest contributor to polycyclic aromatic compound concentrations in traditional foods of the Bigstone Cree Nation in Alberta, Canada[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 275: 116625. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116625 [9] ZHANG X, WANG X L, ZHAO X L, et al. Important but overlooked potential risks of substituted polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon: Looking below the tip of the iceberg[J]. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2022, 260(1): 18. doi: 10.1007/s44169-022-00021-x [10] CHLEBOWSKI A C, GARCIA G R, La DU J K, et al. Mechanistic investigations into the developmental toxicity of nitrated and heterocyclic PAHs[J]. Toxicological Sciences, 2017, 157(1): 246-259. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfx035 [11] KNECHT A L, GOODALE B C, TRUONG L, et al. Comparative developmental toxicity of environmentally relevant oxygenated PAHs[J]. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 2013, 271(2): 266-275. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.05.006 [12] JIANG S L, YANG J, FANG D A. Histological, oxidative and immune changes in response to 9, 10-phenanthrenequione, retene and phenanthrene in Takifugu obscurus liver[J]. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A, Toxic/Hazardous Substances & Environmental Engineering, 2020, 55(7): 827-836. [13] MU J L, WANG J Y, JIN F, et al. Comparative embryotoxicity of phenanthrene and alkyl-phenanthrene to marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma)[J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2014, 85(2): 505-515. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.01.040 [14] 江桂斌. 环境样品前处理技术[M]. 2版. 北京: 化学工业出版社, 2016. JIANG G B. Environmental sample preparation[M]. 2nd ed. Beijing: Chemical Industry Press, 2016(in Chinese).

[15] BANDOWE B A M, MEUSEL H. Nitrated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (nitro-PAHs) in the environment-A review[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2017, 581-582: 237-257. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.12.115 [16] OHURA T, SAWADA K I, AMAGAI T, et al. Discovery of novel halogenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban particulate matters: Occurrence, photostability, and AhR activity[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2009, 43(7): 2269-2275. [17] ÅBERG A, MACLEOD M, WIBERG K. Physical-chemical property data for dibenzo- p -dioxin (DD), dibenzofuran (DF), and chlorinated DD/Fs: A critical review and recommended values[J]. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 2008, 37(4): 1997-2008. doi: 10.1063/1.3005673 [18] MANOUSI N, DELIYANNI E A, ROSENBERG E, et al. Ultrasound-assisted magnetic solid-phase extraction of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and nitrated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from water samples with a magnetic polyaniline modified graphene oxide nanocomposite[J]. Journal of Chromatography A, 2021, 1645: 462104. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2021.462104 [19] LIU Q Z, XU X, WANG L, et al. Simultaneous determination of forty-two parent and halogenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons using solid-phase extraction combined with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry in drinking water[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2019, 181: 241-247. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.06.011 [20] LI J K, LIU Y X, SU H, et al. In situ hydrothermal growth of a zirconium-based porphyrinic metal-organic framework on stainless steel fibers for solid-phase microextraction of nitrated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons[J]. Microchimica Acta, 2017, 184(10): 3809-3815. doi: 10.1007/s00604-017-2403-0 [21] WANG X L, KANG H Y, WU J F. Determination of chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in water by solid-phase extraction coupled with gas chromatography and mass spectrometry[J]. Journal of Separation Science, 2016, 39(9): 1742-1748. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201501286 [22] GUIÑEZ M, CANALES R, MARTINEZ L D, et al. Solvent-based de-emulsification dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction coupled with UPLC-MS/MS for the fast determination of ultratrace levels of nitrated and oxygenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in environmental samples[J]. Analytical Methods, 2018, 10(8): 910-919. doi: 10.1039/C8AY00021B [23] GUIÑEZ M, BAZAN C, MARTINEZ L D, et al. Determination of nitrated and oxygenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in water samples by a liquid–liquid phase microextraction procedure based on the solidification of a floating organic drop followed by solvent assisted back-extraction and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry[J]. Microchemical Journal, 2018, 139: 164-173. doi: 10.1016/j.microc.2018.02.027 [24] LI J Q, ZHAO B, GUO L Y, et al. Synthesis of hypercrosslinked polymers for efficient solid-phase microextraction of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their derivatives followed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry determination[J]. Journal of Chromatography A, 2021, 1653: 462428. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2021.462428 [25] CHONDO Y, LI Y, MAKINO F, et al. Determination of selected nitropolycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in water samples[J]. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin, 2013, 61(12): 1269-1274. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c13-00547 [26] TROUVÉ G, NGO C, ALMOUALLEM W, et al. Development of a liquid/liquid extraction method and GC/MS analysis dedicated to the quantitative analysis of PAHs and O-PACs in groundwater from contaminated sites and soils[J]. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds, 2022, 42(7): 4000-4018. doi: 10.1080/10406638.2021.1880449 [27] ZHU T, RAO Z, GUO F, et al. Simultaneous determination of 32 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon derivatives and parent PAHs using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry: Application in groundwater screening[J]. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2018, 101(5): 664-671. doi: 10.1007/s00128-018-2462-x [28] YAN K, WU S M, GONG G Y, et al. Simultaneous determination of typical chlorinated, oxygenated, and European union priority polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in milk samples and milk powders[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2021, 69(13): 3923-3931. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c00283 [29] dos SANTOS R R, VIDOTTI LEAL L D, de LOURDES CARDEAL Z, et al. Determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their nitrated and oxygenated derivatives in coffee brews using an efficient cold fiber-solid phase microextraction and gas chromatography mass spectrometry method[J]. Journal of Chromatography A, 2019, 1584: 64-71. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2018.11.046 [30] 莫李桂, 马盛韬, 李会茹, 等. 气相色谱/三重四极杆串联质谱法检测土壤中氯代多环芳烃和溴代多环芳烃[J]. 分析化学, 2013, 41(12): 1825-1830. MO L G, MA S T, LI H R, et al. Determination of chlorinated-and brominated-polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soil samples by gas chromatography coupled with triple quadrupole mass spectrometry[J]. Chinese Journal of Analytical Chemistry, 2013, 41(12): 1825-1830 (in Chinese).

[31] PULLEYBLANK C, KELLEHER B, CAMPO P, et al. Recovery of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their oxygenated derivatives in contaminated soils using aminopropyl silica solid phase extraction[J]. Chemosphere, 2020, 258: 127314. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127314 [32] FERNANDO S, JOBST K J, TAGUCHI V Y, et al. Identification of the halogenated compounds resulting from the 1997 Plastimet Inc. fire in Hamilton, Ontario, using comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography and (ultra)high resolution mass spectrometry[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2014, 48(18): 10656-10663. [33] SANKODA K, KURIBAYASHI T, NOMIYAMA K, et al. Occurrence and source of chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (Cl-PAHs) in tidal flats of the Ariake Bay, Japan[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2013, 47(13): 7037-7044. [34] 孙建林, 倪宏刚, 丁超, 等. 深圳茅洲河表层沉积物卤代多环芳烃污染研究[J]. 环境科学, 2012, 33(9): 3089-3096. SUN J L, NI H G, DING C, et al. Halogenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface sediments of Maozhou River, Shenzhen[J]. Environmental Science, 2012, 33(9): 3089-3096 (in Chinese).

[35] MASUDA M, WANG Q, TOKUMURA M, et al. Quantification of brominated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in environmental samples by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry with atmospheric pressure photoionization and post-column infusion of dopant[J]. Analytical Sciences, 2020, 36(9): 1105-1111. doi: 10.2116/analsci.20P025 [36] MA J, HORII Y, CHENG J P, et al. Chlorinated and parent polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in environmental samples from an electronic waste recycling facility and a chemical industrial complex in China[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2009, 43(3): 643-649. [37] 王丽, 金芬, 李敏洁, 等. 分散固相萃取-气相色谱-串联质谱法测定蔬菜中多环芳烃及卤代多环芳烃[J]. 分析化学, 2013, 41(6): 869-875. WANG L, JIN F, LI M J, et al. Determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and halogenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in vegetable by gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry[J]. Chinese Journal of Analytical Chemistry, 2013, 41(6): 869-875 (in Chinese).

[38] de WITTE B, WALGRAEVE C, DEMEESTERE K, et al. Oxygenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in mussels: Analytical method development and occurrence in the Belgian coastal zone[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2019, 26(9): 9065-9078. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-04259-2 [39] ZASTROW L, SPEER K, SCHWIND K H, et al. A sensitive GC-HRMS method for the simultaneous determination of parent and oxygenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in barbecued meat and meat substitutes[J]. Food Chemistry, 2021, 365: 130625. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130625 [40] TANG J, MA S T, LIU R R, et al. The pollution profiles and human exposure risks of chlorinated and brominated PAHs in indoor dusts from e-waste dismantling workshops: Comparison of GC-MS, GC-MS/MS and GC × GC-MS/MS determination methods[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2020, 394: 122573. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122573 [41] HORII Y, OK G, OHURA T, et al. Occurrence and profiles of chlorinated and brominated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in waste incinerators[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2008, 42(6): 1904-1909. [42] 张宇, 王椿, 辛悦, 等. 自组装固相萃取-气相色谱-质谱法测定大气细颗粒物中溴代多环芳烃类化合物[J]. 分析化学, 2023, 51(10): 1641-1650. ZHANG Y, WANG C, XIN Y, et al. Determination of brominated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in atmospheric fine particulate matter by self-assembled solid phase extraction-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry[J]. Chinese Journal of Analytical Chemistry, 2023, 51(10): 1641-1650 (in Chinese).

[43] NYIRI Z, NOVÁK M, BODAI Z, et al. Determination of particulate phase polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their nitrated and oxygenated derivatives using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry[J]. Journal of Chromatography A, 2016, 1472: 88-98. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2016.10.021 [44] VUONG Q T, THANG P Q, NGUYEN T N T, et al. Seasonal variation and gas/particle partitioning of atmospheric halogenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and the effects of meteorological conditions in Ulsan, South Korea[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2020, 263(Pt A): 114592. [45] KAKIMOTO K, NAGAYOSHI H, KONISHI Y, et al. Atmospheric chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in East Asia[J]. Chemosphere, 2014, 111: 40-46. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.03.072 [46] JIN R, LIU G R, ZHENG M H, et al. Congener-specific determination of ultratrace levels of chlorinated and brominated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in atmosphere and industrial stack gas by isotopic dilution gas chromatography/high resolution mass spectrometry method[J]. Journal of Chromatography A, 2017, 1509: 114-122. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2017.06.022 [47] AHMED T M, BERGVALL C, ÅBERG M, et al. Determination of oxygenated and native polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban dust and diesel particulate matter standard reference materials using pressurized liquid extraction and LC-GC/MS[J]. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 2015, 407(2): 427-438. doi: 10.1007/s00216-014-8304-8 [48] LI L J, HO S S H, CHOW J C, et al. Quantification of oxygenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in ambient aerosol samples using in-injection port thermal desorption-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry: Method exploration and validation[J]. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry, 2018, 433: 25-30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2018.08.005 [49] SUN Z, ZHU Y, ZHUO S J, et al. Occurrence of nitro- and oxy-PAHs in agricultural soils in Eastern China and excess lifetime cancer risks from human exposure through soil ingestion[J]. Environmental International, 2017, 108: 261-270. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.09.001 [50] LI W, WANG C, SHEN H Z, et al. Concentrations and origins of nitro-polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and oxy-polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in ambient air in urban and rural areas in Northern China[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2015, 197: 156-164. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2014.12.019 [51] TUTINO M, Di GILIO A, LARICCHIUTA A, et al. An improved method to determine PM-bound nitro-PAHs in ambient air[J]. Chemosphere, 2016, 161: 463-469. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.07.015 [52] XU C, GAO L R, ZHENG M H, et al. Nontarget screening of polycyclic aromatic compounds in atmospheric particulate matter using ultrahigh resolution mass spectrometry and comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2021, 55(1): 109-119. [53] WEI S L, HUANG B, LIU M, et al. Characterization of PM2.5-bound nitrated and oxygenated PAHs in two industrial sites of South China[J]. Atmospheric Research, 2012, 109/110: 76-83. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosres.2012.01.009 [54] BANDOWE B A, MEUSEL H, HUANG R J, et al. PM2.5-bound oxygenated PAHs, nitro-PAHs and parent-PAHs from the atmosphere of a Chinese megacity: Seasonal variation, sources and cancer risk assessment[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2014, 473/474: 77-87. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.11.108 [55] WANG J Z, XU H M, GUINOT B, et al. Concentrations, sources and health effects of parent, oxygenated- and nitrated- polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in middle-school air in Xi'an, China[J]. Atmospheric Research, 2017, 192: 1-10. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosres.2017.03.006 [56] WANG W, JING L, ZHAN J, et al. Nitrated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon pollution during the Shanghai World Expo 2010[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2014, 89: 242-248. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.02.031 [57] BARRADO A I, GARCÍA S, CASTRILLEJO Y, et al. Exploratory data analysis of PAH, nitro-PAH and hydroxy-PAH concentrations in atmospheric PM10-bound aerosol particles. Correlations with physical and chemical factors[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2013, 67: 385-393. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.10.030 [58] ALVES C A, VICENTE A M, CUSTÓDIO D, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their derivatives (nitro-PAHs, oxygenated PAHs, and azaarenes) in PM2.5 from Southern European cities[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2017, 595: 494-504. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.03.256 [59] SOUZA K F, CARVALHO L R F, ALLEN A G, et al. Diurnal and nocturnal measurements of PAH, nitro-PAH, and oxy-PAH compounds in atmospheric particulate matter of a sugar cane burning region[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2014, 83: 193-201. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.11.007 [60] dos SANTOS R R, de LOURDES CARDEAL Z, MENEZES H C. Phase distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their oxygenated and nitrated derivatives in the ambient air of a Brazilian urban area[J]. Chemosphere, 2020, 250: 126223. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126223 [61] CHUESAARD T, CHETIYANUKORNKUL T, KAMEDA T, et al. Influence of biomass burning on the levels of atmospheric polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their nitro derivatives in Chiang Mai, Thailand[J]. Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 2014, 14(4): 1247-1257. doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2013.05.0161 [62] NIU X Y, HO S S H, HO K F, et al. Atmospheric levels and cytotoxicity of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and oxygenated-PAHs in PM2.5 in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2017, 231(Pt 1): 1075-1084. [63] REN Y Q, ZHOU B H, TAO J, et al. Composition and size distribution of airborne particulate PAHs and oxygenated PAHs in two Chinese megacities[J]. Atmospheric Research, 2017, 183: 322-330. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosres.2016.09.015 [64] LEE H H, CHOI N R, LIM H B, et al. Characteristics of oxygenated PAHs in PM10 at Seoul, Korea[J]. Atmospheric Pollution Research, 2018, 9(1): 112-118. doi: 10.1016/j.apr.2017.07.007 [65] SHI M W, ZHANG R Z, WANG Y X, et al. Health risk assessments of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and chlorinated/brominated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban air particles in a haze frequent area in China[J]. Emerging Contaminants, 2020, 6: 172-178. doi: 10.1016/j.emcon.2020.04.002 [66] MA J, CHEN Z Y, WU M H, et al. Airborne PM2.5/PM10-associated chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their parent compounds in a suburban area in Shanghai, China[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2013, 47(14): 7615-7623. [67] 孙建林, 常文静, 陈正侠, 等. 深圳大气颗粒物中卤代多环芳烃污染研究[J]. 环境科学, 2015, 36(5): 1513-1522. SUN J L, CHANG W J, CHEN Z X, et al. Pollution of halogenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in atmospheric particulate matters of Shenzhen[J]. Environmental Science, 2015, 36(5): 1513-1522 (in Chinese).

[68] JIN R, BU D, LIU G R, et al. New classes of organic pollutants in the remote continental environment - Chlorinated and brominated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons on the Tibetan Plateau[J]. Environment International, 2020, 137: 105574. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105574 [69] OHURA T, KAMIYA Y, IKEMORI F. Local and seasonal variations in concentrations of chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons associated with particles in a Japanese megacity[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2016, 312: 254-261. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.03.072 [70] BANDOWE B A M, LUESO M G, WILCKE W. Oxygenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and azaarenes in urban soils: A comparison of a tropical city (Bangkok) with two temperate cities (Bratislava and Gothenburg)[J]. Chemosphere, 2014, 107: 407-414. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.01.017 [71] OHURA T, KITAZAWA A, AMAGAI T. Seasonal variability of 1-chloropyrene on atmospheric particles and photostability in toluene[J]. Chemosphere, 2004, 57(8): 831-837. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2004.08.069 [72] GARCIA K O, TEIXEIRA E C, AGUDELO- CASTAÑEDA D M, et al. Assessment of nitro-polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in PM1 near an area of heavy-duty traffic[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2014, 479/480: 57-65. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.01.126 [73] ISHAQ R, NÄF C, ZEBÜHR Y, et al. PCBs, PCNs, PCDD/Fs, PAHs and Cl-PAHs in air and water particulate samples: Patterns and variations[J]. Chemosphere, 2003, 50(9): 1131-1150. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(02)00701-4 [74] WEI C, BANDOWE B A, HAN Y M, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and their derivatives (alkyl-PAHs, oxygenated-PAHs, nitrated-PAHs and azaarenes) in urban road dusts from Xi'an, Central China[J]. Chemosphere, 2015, 134: 512-520. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.11.052 [75] CAI C Y, LI J Y, WU D, et al. Spatial distribution, emission source and health risk of parent PAHs and derivatives in surface soils from the Yangtze River Delta, Eastern China[J]. Chemosphere, 2017, 178: 301-308. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.03.057 [76] MA T, KONG J J, LI W D, et al. Inventory, source and health risk assessment of nitrated and parent PAHs in agricultural soils over a rural river in Southeast China[J]. Chemosphere, 2023, 329: 138688. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.138688 [77] NIEDERER M. Determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and substitutes (Nitro-, Oxy-PAHs) in urban soil and airborne particulate by GC-MS and NCI-MS/MS[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 1998, 5(4): 209-216. doi: 10.1007/BF02986403 [78] PHAM C T, TANG N, TORIBA A, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and nitropolycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in atmospheric particles and soil at a traffic site in Hanoi, Vietnam[J]. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds, 2015, 35(5): 355-371. doi: 10.1080/10406638.2014.903284 [79] OBRIST D, ZIELINSKA B, PERLINGER J A. Accumulation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and oxygenated PAHs (OPAHs) in organic and mineral soil horizons from four U. S. remote forests[J]. Chemosphere, 2015, 134: 98-105. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.03.087 [80] BANDOWE B A M, BIGALKE M, KOBZA J, et al. Sources and fate of polycyclic aromatic compounds (PAHs, oxygenated PAHs and azaarenes) in forest soil profiles opposite of an aluminium plant[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 630: 83-95. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.02.109 [81] MA J, ZHENG J S, CHEN Z Y, et al. Chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban surface dust and soil of Shanghai, China[J]. Advanced Materials Research, 2012, 610/611/612/613: 2989-2994. [82] WANG Q, MIYAKE Y, AMAGAI T, et al. Halogenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soil and river sediment from E-waste recycling sites in Vietnam[J]. Journal of Water and Environment Technology, 2016, 14(3): 166-176. doi: 10.2965/jwet.15-053 [83] TUE N M, GOTO A, TAKAHASHI S, et al. Soil contamination by halogenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from open burning of e-waste in Agbogbloshie (Accra, Ghana)[J]. Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management, 2017, 19(4): 1324-1332. doi: 10.1007/s10163-016-0568-y [84] QIAO M, QI W X, LIU H J, et al. Occurrence, behavior and removal of typical substituted and parent polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in a biological wastewater treatment plant[J]. Water Research, 2014, 52: 11-19. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.12.032 [85] LIU Q Z, XU X, LIN L H, et al. Occurrence, distribution and ecological risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their derivatives in the effluents of wastewater treatment plants[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 789: 147911. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147911 [86] QIAO M, BAI Y H, CAO W, et al. Impact of secondary effluent from wastewater treatment plants on urban rivers: Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and derivatives[J]. Chemosphere, 2018, 211: 185-191. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.07.167 [87] QIAO M, FU L J, LI Z R, et al. Distribution and ecological risk of substituted and parent polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface waters of the Bai, Chao, and Chaobai Rivers in Northern China[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2020, 257: 113600. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113600 [88] QIAO M, QI W X, LIU H J, et al. Oxygenated, nitrated, methyl and parent polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in rivers of Haihe River System, China: Occurrence, possible formation, and source and fate in a water-shortage area[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2014, 481: 178-185. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.02.050 [89] KONG J J, MA T, CAO X Y, et al. Occurrence, partition behavior, source and ecological risk assessment of nitro-PAHs in the sediment and water of Taige Canal, China[J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences (China), 2023, 124: 782-793. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2022.02.034 [90] YUAN K, QING Q, WANG Y R, et al. Characteristics of chlorinated and brominated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the Pearl River Estuary[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 739: 139774. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139774 [91] MOHAMMED R, ZHANG Z F, HU Y H, et al. Temporal-spatial variation, source forensics of PAHs and their derivatives in sediment from Songhua River, Northeastern China[J]. Environmental Geochemistry and Health, 2022, 44(11): 4031-4043. doi: 10.1007/s10653-021-01106-7 [92] 曾超怡, 徐辉, 许岩, 等. 长江重点江段水体中多环芳烃及其衍生物的分布及健康风险[J]. 环境科学学报, 2021, 41(12): 4932-4941. ZENG C Y, XU H, XU Y, et al. Distribution and health risk of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and their derivatives in surface water of the Yangtze River[J]. Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae, 2021, 41(12): 4932-4941 (in Chinese).

[93] BATENI F, MEHDINIA A, LUNDIN L, et al. Distribution, source and ecological risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the sediments of northern part of the Persian Gulf[J]. Chemosphere, 2022, 295: 133859. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.133859 [94] FUJIWARA F, GUIÑEZ M, CERUTTI S, et al. UHPLC-(+)APCI-MS/MS determination of oxygenated and nitrated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in airborne particulate matter and tree barks collected in Buenos Aires city[J]. Microchemical Journal, 2014, 116: 118-124. doi: 10.1016/j.microc.2014.04.004 [95] NI H G, GUO J Y. Parent and halogenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in seafood from South China and implications for human exposure[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2013, 61(8): 2013-2018. doi: 10.1021/jf304836q [96] WANG L, LI C M, JIAO B N, et al. Halogenated and parent polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in vegetables: Levels, dietary intakes, and health risk assessments[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 616/617: 288-295. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.10.336 [97] WICKRAMA-ARACHCHIGE A U-K, GGURUGE K S, INAGAKI Y, et al. Halogenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in edible aquatic species of two Asian countries: Congener profiles, biomagnification, and human risk assessment[J]. Food Chemistry, 2021, 360: 130072. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130072 [98] HUANG C, XU X, WANG D H, et al. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) activity and DNA-damaging effects of chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (Cl-PAHs)[J]. Chemosphere, 2018, 211: 640-647. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.07.087 -

下载:

下载: