-

当今,随着经济的快速增长,人类开发矿产资源的力度不断加大,由此引发的废物、废水和废气的积累对环境造成了很大的破坏[1-2]。同时在土壤耕作的过程中,化肥、农药和助剂的不合理使用也会导致土壤环境日益恶化,尤其是重金属污染土壤的现象日趋严重,这已成为备受人们关注的热点环境问题[3]。作为典型重金属污染物之一的镉(cadmium,Cd),由于其具有强生物毒性和流动性,并可通过土壤-植物系统转移富集,从而通过食物链对人类健康造成威胁。另外,Cd等重金属难于通过微生物降解或者化学分解而减少危害,其往往会长期存在于受污染的土壤中[4-5]。因此,Cd污染土壤已成为人类和环境健康安全的大隐患。海南省现有的富硒土壤(Se含量≥0.4 mg·kg−1)占全岛总面积的28%以上,说明其在利用富硒土壤资源开发热带富硒农产品方面具有明显的区域优势。但富硒土壤具有伴生Cd等重金属的效应,因此,海南在利用富硒土壤资源的过程中,应正视Cd等重金属污染的潜在风险,这对促进富硒土壤资源的科学利用具有重要的现实意义。

针对重金属污染土壤的几种修复技术,如物理修复技术、化学修复技术、生物修复技术和植物修复技术等[6],已经被开发且广泛应用。目前,原位钝化技术[7-8]因具有环境安全性、简便高效性和低成本性等优点,能减轻生物毒性并降低污染土壤中重金属的生物有效性和利用度,常被用来修复重金属污染土壤。其钝化修复原理是通过添加钝化剂到重金属污染土壤中,促进钝化剂与重金属之间发生吸附、络合、离子交换和氧化还原等一系列作用和反应,从而改变重金属在土壤中的赋存形态,降低其活性,最终实现对重金属污染土壤的修复作用。在众多的钝化修复剂中,磷酸盐、黏土矿物、碱性物质和有机物质等为人们常用[9]。在控制污染土壤中重金属的迁移与转化方面,土壤有机质被认为是最重要的决定因素[10],其中,腐殖质是土壤有机质的主要组成部分。腐殖质依据其在酸、碱溶液中溶解度的不同可分为富里酸(fulvic acids,FA)、胡敏酸(humic acids,HA)和胡敏素(humin,HM)[11]。关于腐殖质对环境中重金属影响的研究大多集中于探讨HA/FA和重金属之间的相互作用方面,有关HM对重金属的环境意义的研究相对较少[12-14]。对于占腐殖质绝大部分的HM,含有大量—COOH、—OH等活性基团,分子质量大且理化性质稳定,可与土壤中重金属发生吸附络合作用[15],从而对土壤中重金属的行为产生关键影响。赤铁矿(hematite,α-Fe2O3)具有一定的吸附性和磁性[16],STAHL等[17]报道,α-Fe2O3通过交换性和非交换性吸附2种模型,吸附土壤中Cd2+、Co2+、Cu2+、Pb2+、Zn2+等重金属,具有防止重金属继续转移扩散的作用。PALLO[18]提出,HM可与土壤中的铁矿物发生相互作用,带负电的HM会依附在带正电的矿物表面膜上,从而形成胡敏素-赤铁矿复合体(HM-α-Fe2O3),且HM和α-Fe2O3结合的程度很大部分取决于它们的分子质量、分子结构和所含有的官能团。

在前人研究[16, 19-20]的基础上,本研究从富硒土壤中提取HM,并将HM和α-Fe2O3进行混合,比较了复合体(HM-α-Fe2O3)、单体(HM)、单体(α-Fe2O3) 3种物质作为富硒土壤中外源Cd污染的钝化剂的应用效果,从对土壤pH(氢潜力)、有效态Cd浓度、Cd形态分布的影响着手进行了分析,可为富硒土壤中重金属污染的修复提供参考。

全文HTML

-

富硒土壤于2018-06-24采自海南省海口市遵谭镇、新坡镇一带地区的菜地(按采样顺序进行编号,1#:N19°50′18″E110°16′28″;2#:N19°50′17″E110°16′30″;3#:N19°49′58″E110°16′40″;4#:N19°49′48″E110°16′36″;5#:N19°49′42″E110°16′33″;6#:N19°49′5″E110°16′57″),按S型随机布5点采集土壤并将其混匀。土壤样品经自然风干、四分法缩分、研磨处理后过20目筛,装袋密闭保存备用。

根据《土壤农业化学分析》记载的方法[21]测定土壤的基本性质,包括pH、土壤有机质、CEC(阳离子交换容量)、全氮和全磷。供试富硒土样经HF-HClO4-HNO3混合酸在高压密封消解后,使用电感耦合等离子体-质谱法(ICP-MS)(NexIOTM300X,美国)测定土样中总Cd和总Se的浓度。基本性质见表1。供试土样的总Se含量为0.466 mg·kg−1,符合富硒土壤的标准值(总Se≥0.4 mg·kg−1)[22],pH偏低,印证了土壤为富硒区酸性土壤。该富硒土壤的总Cd含量低于土壤环境质量规定的二级标准(GB 15618-1995)(Cd≤0.4 mg·kg−1)。

1) α-Fe2O3的制备。按照MULVANEY等[23]提出的水热法,量取1 mol·L−1的FeCl3溶液50 mL,逐滴慢慢加入到先前已煮沸的450 mL超纯水中,在滴加的过程中,观察溶液的颜色变化,当溶液由金黄色变为深红色时,加入最后一滴。待溶液加热5 min后,停止加热,将其静置冷却至室温之后装入透析袋中,在HClO4溶液(pH=3.5)中透析约48 h。溶液以8 000 r·min−1的高速离心15 min,弃去上清液,沉淀物用超纯水清洗多次后,冷冻干燥,然后将样品研磨过60目筛,装袋保存备用。

2) HM的制备。以富硒土壤样品提取制备HM,称取一定量的富硒土壤于100 mL的离心管中,然后加入0.1 mol·L−1 NaOH溶液(土液质量比为1∶10),振荡6 h后,以4 000 r·min−1的速度离心20 min,弃去分离出来的富里酸和胡敏酸上清液。以上步骤重复操作多次,待分离的上清液颜色变为淡黄色即可。接着用超纯水反复清洗固体至其pH为7.0左右,最后通过冷冻干燥获得胡敏素。

3) HM-α-Fe2O3的制备。利用湿法包覆,将HM按一定的比例吸附在α-Fe2O3上,获得HM-α-Fe2O3。具体步骤为,称量1 g HM置于烧杯中,加入适量的20 mmol·L−1 NaCl溶液,然后使用质量分数为5% HCl或NaOH溶液调节溶液pH至中性。接着往里加入2.0 g α-Fe2O3和适量去离子水,控制总固液比为1∶20,然后用磁力搅拌器搅拌24 h。最后将混合物以7 800 r·min−1的速度离心10 min,收集沉淀物并洗涤多次后,进行冷冻干燥,即获得HM-α-Fe2O3。

-

准确称取富硒土壤50 g,置于小塑料盆中,添加浓度水平为10 mg·kg−1的Cd2+溶液,使其与土壤混匀,保持稳定平衡30 d。然后,添加不同剂量的HM(施用率分别为土壤重量的0.5%、1%和2%,其编号为H1、H2和H3)、α-Fe2O3(施用率分别为土壤重量的6%、12%和18%,其编号为F1、F2和F3)或HM-α-Fe2O3复合物(添加水平分别为1、1.5和2.0 g·kg−1,编号为(F-H)1、(F-H)2和(F-H)3),进行钝化实验,同时设置无任何添加的土壤样品50 g作为对照组(表示为CK)。每种钝化处理做3份平行样。将30个小塑料盆处理土壤置于(25±1) ℃的恒温室中,培养60 d,通过每日称重来补充去离子水,使土壤含水率达到田间持水量的70%。分别在培养时间为0、5、10、20和60 d采集适量土壤,冷冻干燥48 h。然后,将冷冻干燥后的土壤样品研磨,过80目尼龙筛,进行后续的分析。

使用扫描电子显微镜SEM(S-3000N 型扫描电子显微镜,日本日立),观察所制备钝化剂的表面形貌特征;使用全自动比表面积与孔隙度分析仪(ASAP2020M+c,美国麦克仪器公司)测定钝化剂的比表面积和孔径大小。在土水比为1∶5的情况下,使用pH酸度计(PHS-3E型,上海仪电科学仪器股份有限公司)测定土壤的pH。使用由0.005 mol·L−1二乙烯三胺五乙酸溶液(diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid, DTPA)、0.1 mol·L−1三乙醇胺溶液(triethanolamine, TEA)和0.01 mol·L−1CaCl2溶液制得的DTPA提取液,提取不同培养时间的钝化处理土壤中的有效态Cd含量[24]。按照TESSIER等[25]提出的连续提取法,分离并测定各种不同化学形态的Cd。土壤溶液中Cd浓度均使用火焰原子吸收分光光度计(TAS-990 AFG型,北京普析通用仪器有限责任公司)测定。

使用Excel 2010分析和绘制数据,并表示为平均值±标准偏差(SD;n=3)。使用Origin 8.0作图并进行数据模型拟合。使用SPSS 22.0进行单因素方差分析,以进行统计学分析,当发现处理数据之间存在显著差异时(P<0.05),通过Duncan测试进行多次比较。

1.1. 实验材料

1.2. 实验方法

-

图1为HM、α-Fe2O3及HM-α-Fe2O3的SEM图。可以看出,HM表面存在丝状纤维并均匀分布,呈大块颗粒,表面具有明显的中孔和少量大孔;α-Fe2O3呈颗粒状,表面有许多颗粒,非常致密,表面具有更明显的中孔;HM-α-Fe2O3呈球形,表面存在一些中孔和一些未发育的孔结构,有利于比表面积增大。

-

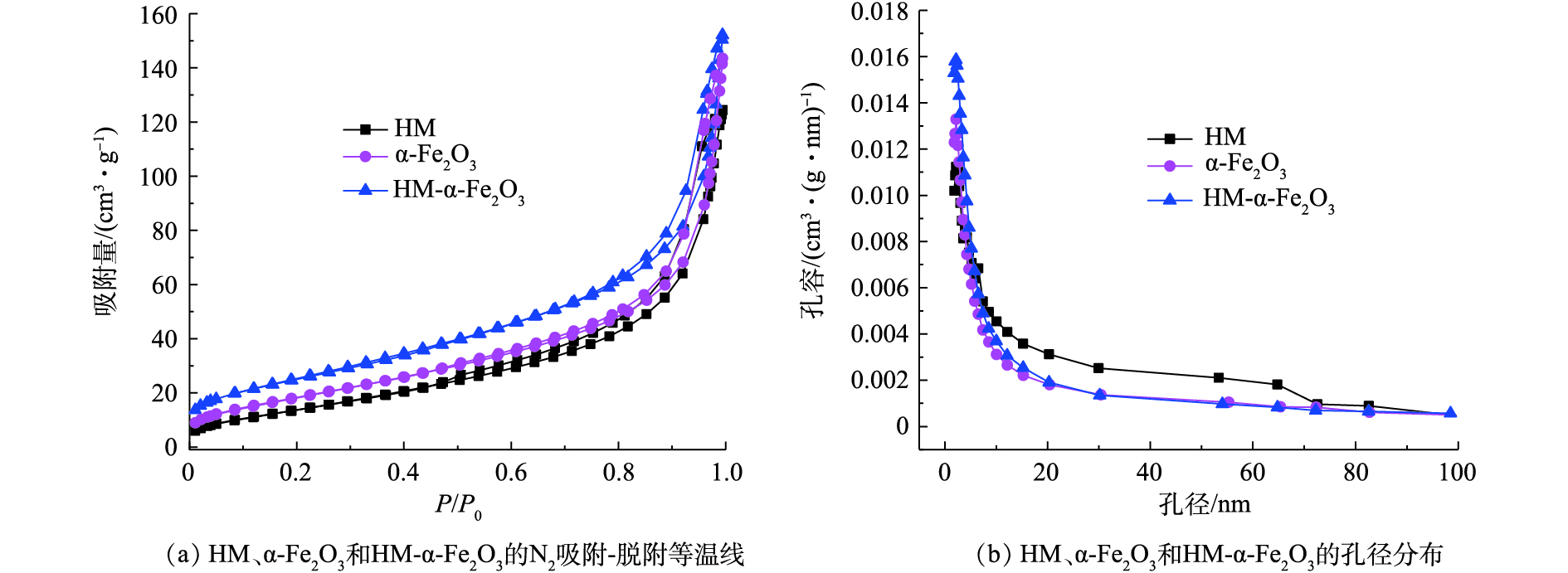

图2为HM、α-Fe2O3和HM-α-Fe2O3的N2吸附-脱附等温线和孔径分布情况。如图2所示,HM、α-Fe2O3和HM-α-Fe2O3的N2吸附-脱附等温线可归类为IV型,其孔径分布都集中在2~50 nm(图2(b)),证明了介孔结构的存在。此外,基于Brunauere-Emmette-Teller模型进行分析得到了如下结果:HM、α-Fe2O3和HM-α-Fe2O3的比表面积分别为58.84、68.08和83.35 m2·g−1,其对应的平均孔径分别为12.74、10.24和12.04 nm。与HM、α-Fe2O3钝化剂相比,复合钝化剂HM-α-Fe2O3的比表面积有所增加,这有利于其对土壤中重金属污染物的吸附。

-

与CK组对比,添加3个水平用量的钝化剂(HM、α-Fe2O3或HM-α-Fe2O3),土壤pH的变化见表2。可以看出,HM或α-Fe2O3处理组的土壤pH均明显高于CK组,其中,α-Fe2O3处理组的土壤pH升高较显著,且在10 d时的改变较大。而HM-α-Fe2O3处理组与CK组相差不大,基本一致。与CK组相比,培养60 d时,F1~F3处理组的土壤pH上升了1.09~2.00;H1~H3处理组的土壤pH上升了0.09~0.43;(F-H)1~(F-H)3处理组的土壤pH上升了0.05~0.09。添加了α-Fe2O3钝化剂的土壤,pH上升较为明显,且随着培养期的延长而增加,其中F2、F3处理组的土壤均呈现弱碱性。这是由于α-Fe2O3的碱性特征,α-Fe2O3含有两性铁羟基(≡Fe—OH)和铁原子等表面基团,其等电点通常在pH=7~9[26]。因此,施用α-Fe2O3作为土壤重金属的钝化剂有使土壤碱性化的风险。

-

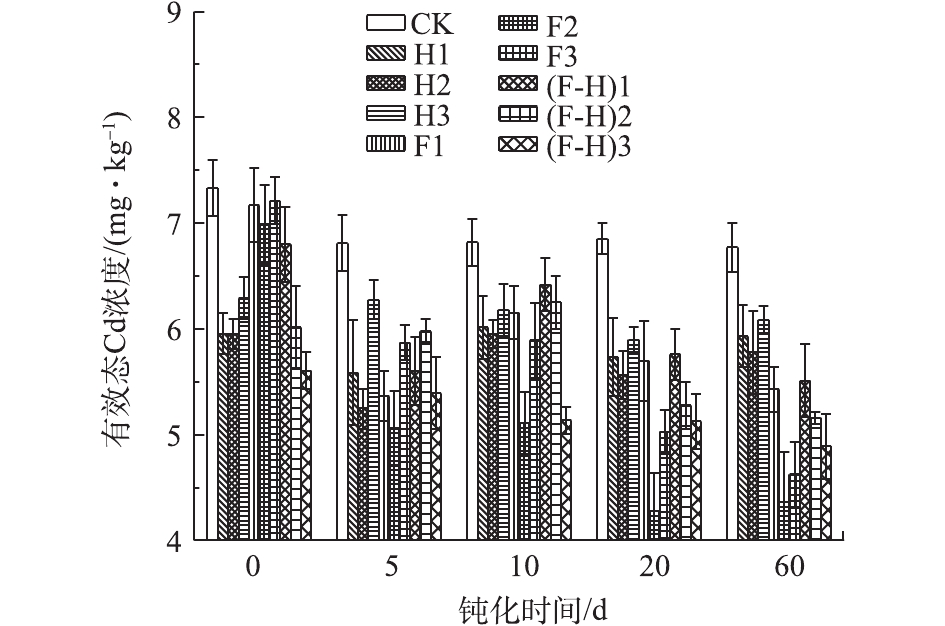

空白组与不同钝化处理组土壤DTPA提取的有效态Cd含量的变化结果见图3。可以看出,CK组土壤中的有效态Cd含量在培养时间5 d时有所降低,之后基本维持较稳定的含量状态((6.92±0.21) mg·kg−1)。不同钝化处理组土壤随着施用量和培养时间的增加,土壤中有效态Cd浓度均出现了不同程度的降低。在钝化处理的60 d范围内,以HM、α-Fe2O3和HM-α-Fe2O3分别作为钝化剂,分别添加3个水平的用量,使土壤有效态Cd含量的降低率(相对于CK处理)分别从7.85%~11.79%、1.64%~4.69%和4.30%~20.85%增加至14.21%~22.96%、21.25%~37.55%和13.45%~27.75%。

各种钝化剂施用效果呈现不同的规律。 HM处理组土壤中有效态Cd含量的减少率在5 d时达到最大,之后有效态Cd含量有所回升并呈现基本稳定的波动状态,各用量中以H2钝化效果较好。HM的钝化作用,与其具有一定的比表面积且含有能够与Cd2+发生络合作用的—COOH、—OH等活性基团有关。α-Fe2O3处理组土壤中有效态Cd含量,在整个培养期内逐渐降低且幅度最大,在60 d时,施加率为12%(F2)组土壤显示出最优的钝化效果。此时土壤呈弱碱性,其表面负电荷有所增加,并伴随着表面吸附点的增加,产生Cd [Cd(OH)+]的羟基态,这种状态与土壤吸附点的亲和力比,金属离子的自由态更强[27],从而使α-Fe2O3产生较强的钝化效果。HM-α-Fe2O3处理组土壤中有效态Cd含量在整个培养期内,呈现逐渐降低的趋势(除5 d外),且以(F-H)3钝化效果最佳。通过相关性分析结果可得,有效态Cd浓度的降低量与钝化剂用量、钝化时间都呈极显著正相关(r=0.631,0.428)(P<0.01)。表明复合型钝化剂HM-α-Fe2O3的吸附和活性点的作用可能分布较均匀,且作用周期较长,从而使其钝化效果与用量、时间呈现出较好的线性增长关系,考虑到其施用率较低,该钝化剂具有较好的应用潜力,可通过提高施用率来挖掘潜力,并适宜于修复周期较长的需要。

土壤pH对有效态Cd的含量有重要影响。研究[28]表明,当土壤pH升高时,可以促进大部分重金属进行表面络合作用,使其固定。pH与有效态Cd浓度呈显著负相关(r=−0.729)(0.01<P<0.05)。这一发现与JAFARNEJADI等[29]的研究结果一致。

-

土壤中重金属的各种形态随着土壤环境因素的变化而变化,而这种变化往往处于动态平衡状态。图4为应用3种钝化剂后,土壤中Cd的各种形态含量随时间的变化情况。由图4可见,与CK组相比,添加钝化剂后,可交换态Cd的含量均有所降低,其中在10 d内变化较大(主要为降低),随后趋于稳定,其中α-Fe2O3处理组土壤中可交换态Cd的含量水平最低(当然其施用率也较高)。碳酸盐结合态Cd的含量,以CK组最低,H3组最高,钝化后均有所升高,其中在5 d时升高最明显,随后有所下降(10~20 d)。铁锰氧化物结合态Cd的含量,以CK组最低,以F1~F3组最高,钝化后,其变化特征为,前20 d逐渐上升,20 d后快速降低,其中以60 d时最低,甚至接近CK组的水平。这可能由于发生了铁锰氧化物的还原溶解,将Fe和Mn固定为硫化物化合物[30]。有机物结合态Cd的含量,以CK组最低,以F1~F3组最高,钝化后最初升高较为明显,随后趋于平稳。残留态Cd的含量,以CK组最低,以F3、(F-H)2和(F-H)3组最高,钝化后最初增加较为显著,随后明显趋于稳定。根据相关性分析结果,投加HM钝化剂后,投加量与土壤中可交换态Cd、碳酸盐结合态Cd和残留态Cd含量之间的关系分别呈负相关(r=−0.136)(P>0.05)、极显著正相关(r=0.753)(P<0.01)和显著正相关(r=0.558)(0.01<P<0.05);投加α-Fe2O3钝化剂后,投加量与土壤中可交换态Cd含量呈极显著负相关(r=−0.870),而与残留态Cd含量之间的关系呈极显著正相关(r=0.654)(P<0.01);投加HM-α-Fe2O3复合钝化剂后,投加量与土壤中可交换态Cd、铁锰氧化物结合态Cd含量呈负相关(r=−0.099,−0.485)(P>0.05),而与碳酸盐结合态Cd、残留态Cd含量之间的关系分别呈极显著正相关(r=0.654)(P<0.01)和显著正相关(r=0.632)(0.01<P<0.05)。这些结果表明,生物可利用的Cd(可交换态)主要转化为生物学不可利用状态Cd(残留态),从而降低Cd的活性。这一发现与CHEN等[31]的研究结果一致。此外,有研究人员发现,修复剂的施用也可以增加可交换态Cd的浓度[32],这可能与外源Cd的不同污染水平促进了土壤中的微生物活动有关。

以钝化60 d时Cd的形态分布(图5)来比较不同钝化处理组与空白组(CK)Cd的形态转化特征。CK组土壤中Cd的形态以可交换态为主,占比为62.29%,残留态、铁锰氧化物结合态和碳酸盐结合态的Cd占比分别为14.44%、11.82%和8.8%,而有机物结合态Cd占比仅为2.66%。与CK组对比,钝化处理组在不同的程度上减少了土壤中可交换态Cd的比例。具体表现在HM、α-Fe2O3和HM-α-Fe2O3处理组中该比例分别降低了17.77%~23.34%、33.93%~45.39%和18.56%~22.07%。此外,不同钝化剂处理后,其土壤中Cd形态分布的变化规律不同。α-Fe2O3的应用对残留态Cd的影响较显著,其占比增加了22.21%~33.04%,且比例随钝化剂施加量的增加而增加,以F3的效果为最佳;HM则对碳酸盐结合态Cd的影响较显著,其占比增加了10.72%~15.38%;相比其他3种形态,HM-α-Fe2O3对残留态Cd影响也较大,其比例增加了13.24%~21.10%。然而,在所有的处理组中,有机物结合态Cd含量均很低,仅占总Cd含量的较低比例,但其含量较为稳定。

可交换态Cd是潜在生物可利用元素的重要指标,在对Cd污染富硒土壤进行各种修复后,可交换部分Cd均小于CK处理组。由于Cd的可交换和碳酸盐结合部分具有高生物利用度,其可以转化为残留态,以降低Cd的迁移率和有效性。HM、α-Fe2O3和HM-α-Fe2O3固定土壤中Cd,分析这可能是Cd通过与离子化的羟基基团形成了络合物,也可能是由于Cd与碳酸盐中含量丰富的

${\rm{CO}}_3^{2 - }$ 或${\rm{PO}}_3^{4 - }$ 形成沉淀来实现的。

2.1. 钝化剂的SEM图分析

2.2. 钝化剂的N2吸附-脱附分析

2.3. 钝化剂对土壤pH的影响

2.4. 土壤中有效态Cd浓度的变化规律

2.5. 重金属Cd的形态分布与转化规律

-

1)添加HM、α-Fe2O3和HM-α-Fe2O3可以不同程度地减少外源Cd污染富硒土壤中的有效态Cd浓度。由于其比表面积较大,因此,HM-α-Fe2O3复合钝化剂对土壤中重金属污染物具有较强的吸附性能。其中,处理组(F-H)3(60 d)对土壤有效态Cd含量的降低率高达27.75%,说明HM-α-Fe2O3可用于稳定化修复重金属污染土壤。

2)有效态Cd浓度与土壤pH呈显著负相关(r=−0.729)(0.01<P<0.05),随着pH的增加,Cd的流动性和生物利用度有所降低。HM-α-Fe2O3处理组的pH与CK组基本一致,在有效修复外源Cd污染富硒土壤的同时,能够维持土壤pH的稳定。

3)不同钝化剂对土壤中Cd不同形态的转化特征存在差异性,总体来说,主要是由可交换态Cd转化为残留态Cd。HM-α-Fe2O3复合处理结合了HM和α-Fe2O3这2种单独处理的优点,改善了各种Cd形态的转化和分布。

4)从污染土壤的修复效果来看,复合钝化剂的钝化效果与用量、时间呈现出较好的线性关系,施用率较低且效果明显。未来可通过提高HM-α-Fe2O3施用率来挖潜,并适宜于修复周期较长的需要。

下载:

下载: