-

NH3是大气中主要的碱性气体,进入大气后与酸性气体(SO2、NOx等)反应产生二次颗粒物,是PM2.5形成的重要原因[1]。大气中氨气通过干湿沉降进入水体后,使水体氮素增加,导致水体富营养化;进入土壤后,在土壤微生物作用下转化为硝态氮,导致土壤酸化[2-3]。大量氨气进入生态系统,会改变生态系统中物种竞争格局,降低物种的多样性[4]。

直接通量测量发现植被冠层是NH3的排放源[5-7]。冠层与大气的氨交换主要由叶表氨交换、叶片气孔氨交换及土壤氨气双向交换组成。叶-大气NH3交换的过程通常为双向交换,交换平衡时NH3浓度称为气孔NH3补偿点(χs)[8]。当大气NH3浓度高于χs时,植被吸收NH3,反之亦然[9-11]。χs估算较为困难,常用叶片质外体中

${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度与H+浓度的比值来代替χs评估植被NH3排放的可能性,该比值称为氨排放潜势(Γ)[12]。Γ一个无量纲的指标,受植被类型、植物生长发育期、谷氨酰胺合成酶(GS)活性等因素影响[12-13]。土壤含氮量直接影响植被${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 吸收量,因此施肥对Γ值影响较大[13-14],不同氮素种类也会通过影响质外体pH值改变Γ值的大小[15]。尿素是我国主要的氮肥品种,施肥后导致大量NH3挥发。添加脲酶抑制剂作为一种有效抑制尿素氨挥发的措施被广泛研究[16-20]。研究发现,硝化抑制剂双氰胺(DCD) 和脲酶抑制剂氢醌(HQ) 混合施用时,可增加肥料作用时间,提高土壤肥效[21]。抑制剂同样能够促进土壤细菌、真菌和放线菌生长[22],还能减少氧化亚氮与其他温室气体的排放,提高肥效[23-24]。总之,脲酶抑制剂能够有效地抑制土壤脲酶活性,延缓尿素水解,降低土壤氨挥发。添加脲酶抑制剂导致植被N吸收增加,改变叶组织中

${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度,影响Γ值及氨排放通量。当前添加脲酶抑制剂评估集中在土壤-大气气体交换通量[23, 25],忽略了对植被排放的影响。本研究对比了单独施加尿素(NS)、尿素添加脲酶抑制剂(NS+YZ)的两种处理小麦氨排放潜势的差异,综合评估添加脲酶抑制剂后小麦NH3通量变化特征。这些结论为进一步评估施肥类型对植被氨排放潜势及通量的影响有重要意义。

全文HTML

-

选取冬小麦(轮选987)于2019年4月19日(拔节期)至5月29日(成熟期)在北京林业大学试验基地开展田间试验。试验共设置2个处理,分为施加尿素+脲酶抑制剂处理(NS+YZ)与单施尿素处理(NS),每个处理设置3个重复。两种处理下基肥施用均按照传统施肥水平150 kg N·ha−1施用,为使结果明显,追肥水平按照270 kg N·ha−1施用,NS+YZ处理抑制剂与尿素比例为1∶100,施肥日期为4月19日。4月19日、4月24日、4月27日、5月5日、5月25日发生了灌溉或降水事件,记录水量(mm)。选择天气晴朗、风速较低的日期(5月9日)测量地表1 m高度处大气氨浓度日间的变化,同步测量小麦叶片气孔导度与氨补偿点日间变化。试验期间每天采集小麦叶和土壤样品,测量

${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度及pH。供试麦田土壤本底pH值为7.68,有机质含量为21.9 g·kg−1,总氮含量为1.8 g·kg−1。供试肥料为尿素(以N计 46%)和脲酶抑制剂(NBPT,购买于美国巴斯夫公司)。 -

小麦质外体

${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 及pH值测定:随机选取小麦个体,剪取15片冠层中部发育良好的小麦叶片立即放置于去离子水中保存,每种处理3个重复。样品采集后30 min内完成分析测定。于4月29日、5月7日、5月20日参照Husted等[26]研究方法进行小麦叶片质外体提取及质外体气体体积(Vair)、液体体积(Vapo)的测定,稀释倍数及对应日期如表1。使用MDH试剂盒测量质外体MDH酶活性,检测细胞质污染,未发现质外体中含有MDH酶。使用ICS-1100(DINOX)离子色谱测量小麦质外体${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度,STARA2110微量pH计测量小麦质外体pH值。土壤

${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度及pH值测定:采集0—10 cm土壤样品−20 ℃冷冻保存,记录土壤湿度。测量时计算并称取含5 g干土的土壤置于50 mL离心管中,加入25 mL氯化钾溶液(2 mol·L−1),塞紧塞子于震荡机震荡1 h后离心(4000 r·min−1)15 min,使用0.45 μm滤膜过滤上清液后在−4 ℃环境中保存。使用AA3连续流动分析仪测量土壤${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度,STARA2110微量pH计测量pH值,每种处理3个重复。麦田大气NH3浓度及气孔导度测量:于5月9日07:00、10:00、13:00、16:00、19:00按上述方法采集小麦叶片进行小麦质外体

${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 及pH值测定。利用便携式温室气体分析仪(LGR,美国)于采样前后半小时连续测量麦田近地面1 m处大气氨浓度。使用Li-6400便携式光合仪进行叶片气孔导度测量。 -

小麦氨排放潜势计算参照Husted等[26]方法,由于质外体渗透离心过程质外体被渗透液稀释,小麦质外体

${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 及H+实际浓度及小麦气孔氨排放潜势计算如下:其中,[

${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ ]实为${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 实际浓度,[${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ ]测为${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 测量浓度;[H+]实为H+实际浓度,[H+]测为H+测量浓度。土壤氨排放潜势(Γg)计算如下:

其中,[

${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ ]g为土壤${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度,[H+]g为土壤H+浓度。小麦气孔氨补偿点计算参照Massad等[12]方法,小麦气孔氨补偿点及氨气通量(Fs)计算:

式中,T为叶片温度,

${R_{{\rm{sNH_3}}}} $ 为小麦气孔NH3阻力,${R_{{\rm{sH_2O}}}} $ 为小麦气孔水蒸气阻力,${D_{{\rm{NH_3}}}} $ 为小麦气孔NH3导度,${D_{{\rm{H_2O}}}} $ 为小麦气孔水蒸气导度,χsz0为高度1 m处大气NH3浓度。

1.1. 试验设计

1.2. 样品采集与测定

1.3. 小麦气孔氨排放潜势(Γs)、气孔氨补偿点(χs)与通量计算

-

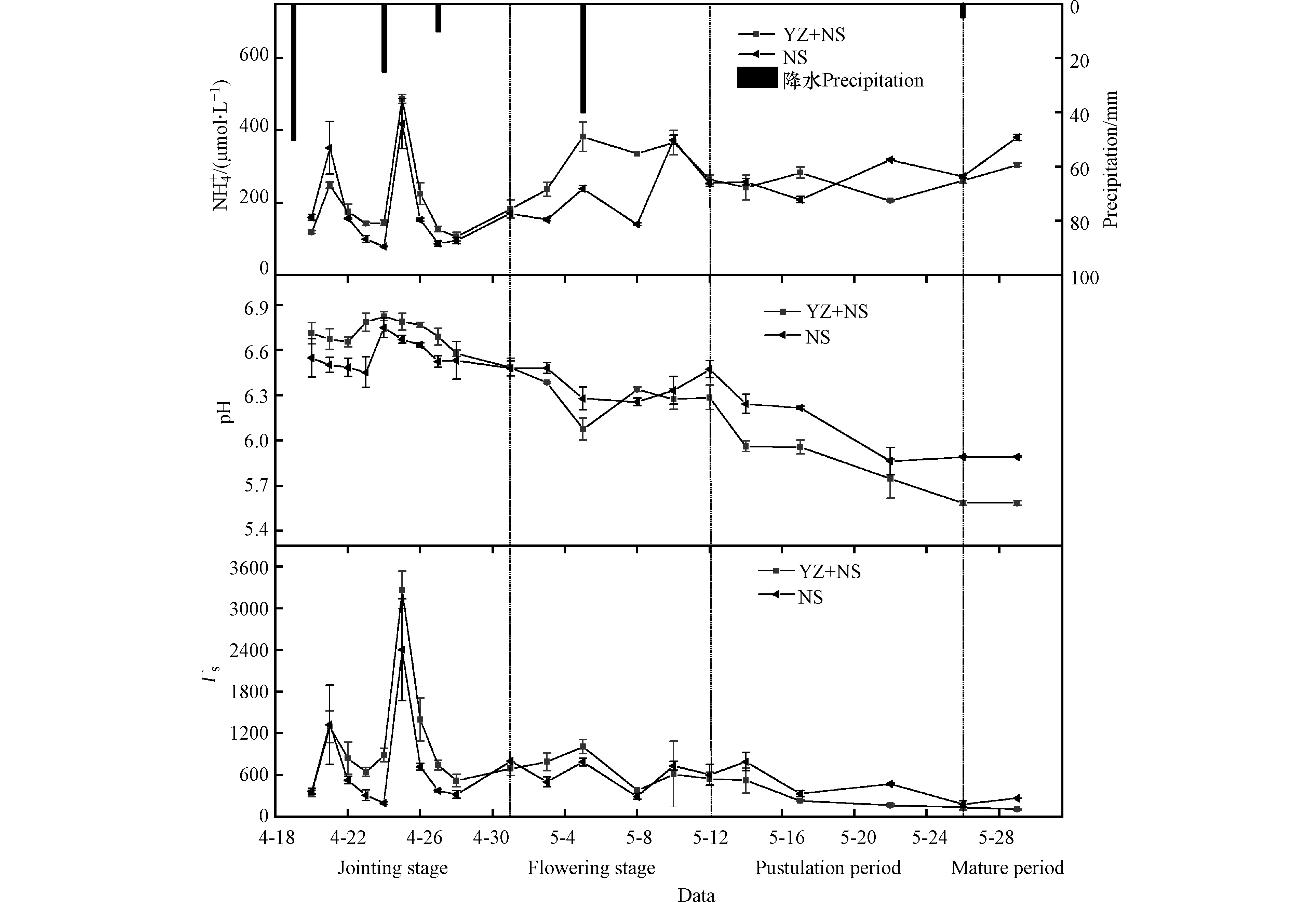

根据小麦生长期将小麦分为拔节抽穗期(4月19日—5月1日)、扬花期(5月1日—5月12日)、灌浆期(5月12日—5月26日)及成熟期(5月26日—5月29日),不同时期NS+YZ及NS两种处理下小麦质外体

${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 、H+浓度和Γs值见图1。NS+YZ及NS处理下小麦质外体${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度分别为(238.72±98.85)μmol·L−1、(224.28±109.38)μmol·L−1(平均值±标准差)。施肥后两次降水(4月19日及4月24日)导致质外体${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度出现两次峰值及pH值的两次升高;扬花期的降水使得pH及${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度同时下降。这是由于追肥后降水促进了尿素水解,加速了小麦对土壤${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 值的吸收,使得质外体中${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 含量明显升高,同时使质外体产生较高的pH值。此外扬花期时肥料水解完全(图2(b)),小麦质外体pH主要受到土壤湿度影响:降水事件发生前土壤湿度(图2(a))较低,产生了土壤干旱胁迫,质外体有较高pH值,降水后干旱胁迫消失,pH值明显降低[27-28]。Γs值主要受${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度及pH值的影响,总体来看,追肥后的降水会导致 Γs值明显上升,而扬花期土壤较为干旱时,灌溉及降水会使 Γs值降低。试验期间,两种处理小麦质外体

${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度均在施肥后(拔节期)显著升高,至扬花期时再次上升,扬花期后期开始下降后到成熟期开始上升。这是由于拔节期肥料添加供给了小麦生长所需要的养分,小麦大量吸收土壤氮素,导致质外体${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度上升;扬花期后期至灌浆期铵根离子浓度稍有下降,这主要受到小麦体内谷氨酰氨合成酶、光合特征变化影响[29];小麦成熟后,叶片衰老会伴随蛋白质等有机物质的分解,植物释放大量NH3[30]。小麦Γs值在施肥后同样出现两次峰值,但扬花期及成熟期 Γs变化较为平缓。这是由于扬花期及成熟期小麦质外体pH值逐渐降低,导致Γs值并未随${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度上升而上升。这说明在拔节期至扬花期时期内,小麦氨排放潜势的增加主要是由于施肥导致的。由图1(a)可看出,NS+YZ处理中质外体

${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度在第一个峰值时小于NS处理,随后NS+YZ处理${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度整体高于NS处理。这是由于施肥后降水时,脲酶抑制剂的添加导致NS+YZ处理相较于NS处理肥料水解更为缓慢,从而在第一个峰值时NS处理土壤${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度(图2(a))较高,导致小麦质外体${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度较高[31]。快速的水解造成了土壤的大量氨挥发,降低了肥料利用效率,而脲酶抑制剂的添加使尿素水解较为缓慢,其肥效更久,导致NS+YZ处理在第一个质外体${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度峰值过后其浓度超过NS处理。试验期间NS+YZ处理Γs值明显高于NS处理,分别为769.21±701.57、619.48±549.99。这表明NS+YZ处理较高的质外体${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度导致其具有较大Γs值,小麦气孔氨排放可能性更大。 -

土壤

${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度、pH值及Γg值变化见图2。施肥后土壤${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度迅速达到最高值,随后逐渐降低,一周后趋于稳定,NS+YZ和NS处理土壤${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度分别为(0.51±0.72)mmol·L−1、(1.25±3.29 )mmol·L−1(平均值±标准差)。这表明尿素在土壤中两周内水解完全,随后的降水对土壤${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度影响较小。在试验期内土壤pH值变化不明显,NS+YZ处理与YZ处理pH值分别为:7.66±0.06、7.65±0.09(平均值±标准差)。与${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度类似,土壤Γg变化同样呈现逐渐降低的趋势,一周后基本稳定,表明土壤氨气的挥发主要与施肥活动相关,这与Massad等[12]研究结果类似。对比两种处理,施肥后NS处理下土壤${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度和Γg远高于NS+YZ处理,说明脲酶抑制剂能够有效抑制尿素水解,降低土壤${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度及Γg,减少土壤氨挥发。 -

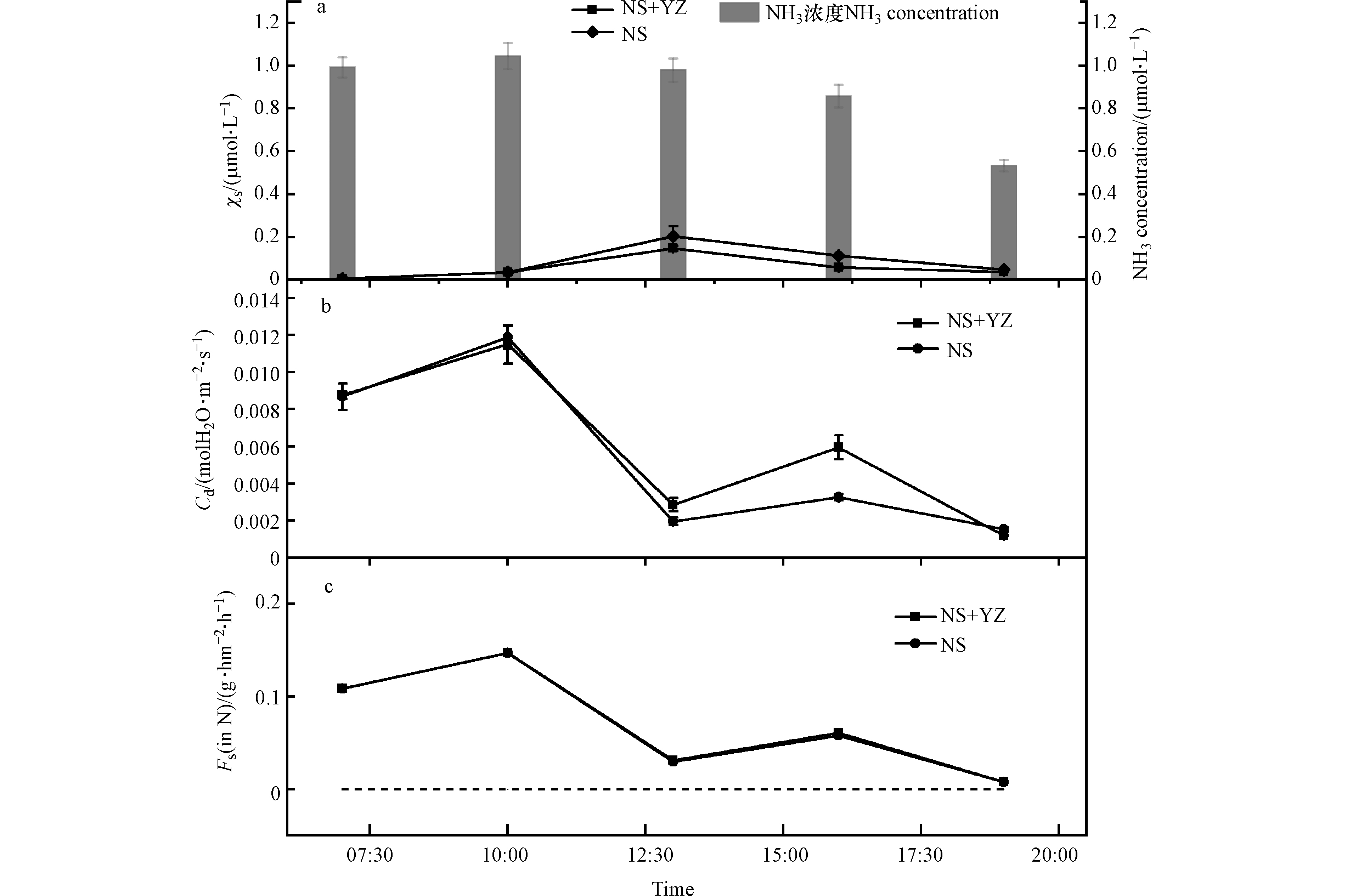

小麦氨补偿点、气孔导度及排放通量变化特征见图3。NS+YZ处理与NS处理小麦χs的变化范围分别为(0.056±0.051)μmol·L−1、(0.080±0.076)μmol·L−1,均呈现出先增加后降低的趋势,最高值出现在午时13:00。由图3可知,扬花期小麦气孔主要起到吸收NH3的作用。而由图3(c)可知,χs 最高点时气孔NH3吸收量较低,这表明χs大小主要受到小麦自身生理状况影响:小麦质外体溶液构成了一个较大的

${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 动态池,通过与叶肉细胞的${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 交换而使其具有较大的${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 日间变化动态,这与Husted等[32]研究一致。比较两种处理发现在上午10:00之前χs变化基本一致,随后NS处理χs上升趋势较NS+YZ处理明显,说明不同施肥处理可能会影响叶片质外体${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 动态池的转化吸收过程,进而影响NH3排放潜势。对小麦气孔的NH3交换通量结果的计算见图3(c)。结果表明,在日间,气孔吸收通量与气孔导度变化趋势(图3(b))一致,呈现出明显的双峰规律,气孔最大吸收通量出现在上午10:00,NS+YZ处理及NS处理均为:(0.147±0.001) g·hm−2·h−1。最小吸收通量出现在下午19:00,NS+YZ处理及NS处理均为(0.008±3.440×10−5 )g·hm−2·h−1。这表明此时气孔-大气NH3交换通量大小主要受到气孔导度控制,与两者浓度梯度关系较小。

2.1.

两种施肥处理下小麦质外体${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 、pH值及Γs变化特征

2.2.

不同施肥处理下土壤${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度、pH值及土壤排放潜势(Γg)变化特征

2.3. 扬花期小麦气孔补偿点(χs)及排放通量(Fs)变化特征

-

试验期间小麦Γs值随生长期变化明显,扬花期及衰老期Γs值较高,灌浆期Γs值较低。施肥及施肥后降水均导致小麦Γs值明显上升,土壤干旱时的降水导致Γs值下降。小麦扬花期小麦气孔起到吸收NH3的作用,吸收通量主要受到气孔导度影响。两种施肥处理下叶片Γs具有较大的差异,NS+YZ处理的

${\rm{NH}}_4^{+} $ 浓度及Γs值明显高于NS处理。Γs与Γg比较发现,虽然脲酶抑制剂的添加降低土壤氨排放潜势,但增加小麦叶片氨排放潜势,因此评估脲酶抑制剂对氨排放的影响时需结合土壤-植被共同评估,这些发现对理解脲酶抑制剂对农田NH3排放的影响有重要意义。

下载:

下载: