-

近年来,卤系阻燃剂由于持久性、生物毒性、生物富集性等缺点,正逐渐被磷系阻燃剂和无机阻燃剂所取代. 有机磷酸酯(organophosphate esters, OPEs)阻燃剂作为重要的有机磷系阻燃剂,在世界范围内被广泛生产和使用. 我国是OPEs的生产和使用大国,2013年我国有机磷阻燃剂的年产量接近31万t,消费量占全球总消费量的16%[1]. OPEs常用于室内建筑材料、家具、塑料和电子产品[2]. OPEs通常是以物理方式而非化学键合添加的,因此极易因挥发和磨损释放到环境中,增加室内OPEs的暴露风险[3-4]. 研究显示,灰尘[5-6]、空气[5–7]、土壤[8-9]、水体[7,9]、植物[10]、动物[10],甚至人类的尿液[11–13]、血液[14–16]、头发[17–19]、指甲[19]等样品中含有较高浓度的OPEs,这表明OPEs在环境中无处不在. OPEs作为新兴有机污染物,具有多种生物毒性,并且会生物富集[20]. 如磷酸三(2-氯乙基)酯(TCEP)、三(1-氯-2-丙基)磷酸酯(TCIPP)和三(1, 3-二氯-2-丙基)磷酸酯(TDCIPP)被证明具有神经毒性和致癌性[21]. TDCIPP和TCIPP也与甲状腺激素和雌激素紊乱有关[22-23]. 磷酸三苯酯(TPHP)已被证明可以诱导雌激素效应以及潜在的发育和神经毒性[23-24],TCEP也被欧盟列为2类致癌物[8]. 目前研究发现,室内环境中OPEs的浓度水平普遍是室外环境的数十至数千倍[9,21]. 室内作为人们每天长时间生活和工作的场所,极易因闭塞的空气流动和狭小的空间导致OPEs污染的积聚,致使OPEs的人体暴露风险显著增加.

相较于主动采样,被动采样具有轻捷简便、成本低廉、操作简单、无需电源等优势. 聚氨酯泡沫(PUF)被动采样器已被广泛用于各种半挥发性有机污染物(SVOCs)的室内空气采样研究[25-26]. 聚二甲基硅氧烷(PDMS,又称硅胶)薄片和胸牌可用作室内空气和个体的被动采样研究[27-28]. 有学者利用硅胶手环(wristband, WB)作为个体被动采样器研究个体暴露,发现其具有一定的时间和空间敏感性[29]. 硅胶手环不会干扰参与者的活动,还能够提供个体环境污染物的时间加权平均浓度[30]. 此外,低密度聚乙烯(LDPE)也被用作多种阻燃剂的被动采样[31-32]. LDPE、PUF、PDMS、WB 4种被动采样材料无需过高的成本和复杂的技术,能够在几周至几个月的时间内获得空气中SVOCs的平均浓度,因此在研究室内空气OPEs上也具有良好的前景.

目前关于室内空气OPEs的被动采样研究相对较少,且多集中在欧美国家. Saini等利用全封闭和半封闭式XAD-PUF(SIP)和PUF作为室内被动空气采样器,对加拿大室内空气溴代阻燃剂和增塑剂进行被动采样研究,发现SIP和PUF采样效率约为3.5 m3·d−1[33]. Okeme等还利用PDMS和XAD-Pocket(苯乙烯-二乙烯基苯共聚物)对多伦多大学办公室气相和颗粒相SVOCs进行研究,实验表明PDMS比XAD-Pocket具有更高的采样效率[34]. Saini等使用PUF和XAD-4树脂浸渍的PUF采集室内空气中的邻苯二甲酸酯(PAEs)和溴代阻燃剂(BFRs),研究表明PUF更适合评估BFRs的室内空气浓度,而XAD-4-PUF更适合评估PAEs的空气浓度[33].

虽然已有少量研究[33-34]利用被动采样技术考察了室内空气OPEs污染状况,但仍非常有限,且缺乏各种被动采样材料采样速率和采样效果的对比研究. 本研究利用LDPE、PUF、WB、PDMS 4种被动采样技术,进行了室内空气9种典型OPEs(表1)的采样研究,并利用主动采样对被动采样速率进行了校正,通过分析OPEs的含量、组成及时间累积曲线,对比了4种材料的采样速率和效果,为准确研究室内OPEs污染状况和人体暴露提供技术支持.

-

被动采样材料分别经丙酮、二氯甲烷索氏提取净化72 h后,悬挂在同一室内距离地面2 m高处采样,每个时间点设置3个平行;同时利用1台低流量主动空气采样器同步24 h连续采集室内气态和颗粒态样品(流速4 L·min−1). PDMS条带尺寸:10 cm×5 cm×0.1 cm,LDPE条带尺寸:12.5 cm×4 cm×0.005 cm,采样时间为0、5、10、20、30、40 d;硅胶手环WB尺寸:19.5 cm×1.2 cm×0.2 cm,采样时间为0、2、5、7、20、30、40 d. 被动PUF尺寸:ϕ 14 cm×1.2 cm,采样时间为 0、20、40 d. 主动气态采样PUF尺寸:ϕ 2 cm×9 cm,颗粒态采样玻璃滤膜(GF/F)尺寸:ϕ 4 cm(450 ºC,4 h).

-

(1)PDMS、WB及LDPE:PDMS、WB样品无需清洗,直接整片放入离心管,加入100 ng回收率指示剂(d12-TCEP和d15-TPHP)平衡2 h,再加入10 mL乙酸乙酯,摇床120 r·min−1振荡提取30 min,重复3次. 萃取液合并后经硅胶柱(1 g, 6 mL)净化,待上机检测. LDPE萃取方法同上,萃取溶剂为丙酮∶正己烷∶二氯甲烷=1∶2∶2混合溶剂.

(2)玻璃滤膜:样品中加入回收率指示剂,再加入丙酮∶正己烷∶二氯甲烷=1∶2∶2混合溶剂,超声萃取20 min,重复3次. 萃取液经硅胶柱净化,待上机检测.

(3)PUF:样品中加入回收率指示剂,利用正己烷∶乙酸乙酯=1∶1的混合溶剂,100 ºC加速溶剂萃取5 min,循环2次. 萃取液经硅胶柱净化,待上机检测.

-

OPEs的检测方法以气相色谱-质谱联用法为主[35]. 本研究共分析了9种OPEs单体,如表1所示. 利用SH-RXI-5sil MS (30.0 m×0.25 mm×0.25 μm) 色谱柱分离、进样口温度为280 ℃,载气为高纯He,流量1.5 mL·min−1. 升温程序: 70℃(保持1 min ),以15 ℃·min−1升至300 ℃(保持10 min). EI源,SIM模式,离子源温度为230 ℃,接口温度为280 ℃.

-

所有玻璃器皿均依次用洗液、自来水和去离子水冲洗、烘干,并450 ℃煅烧4 h,使用前用溶剂润洗3次[36]. 实验流程中的质量控制措施包括程序空白、样品平行、添加回收率. 空白样品中仅检出痕量TNBP和TCEP,且均低于样品含量的5%. d12-TCEP和d15-TPHP回收率分别为:70.2%—111%和71.5%—117%.

-

利用主动采样测定的浓度校正被动采样的速率,如下:

式中,Mp为被动样品中待测物质量(ng);Ca和Cp分别为相同时间段主动和被动测得的待测物浓度(ng·m−3),且Ca=Cp;Vp为被动采样体积(m3);vp为被动采样速率(m3·d−1·dm−2);t为采样天数(d);S为被动采样材料表面积(dm2).

-

主动采样显示室内空气OPEs的浓度随时间波动显著,可能与污染源以及通风有关. 主动采样测得的气态OPEs总浓度8.00—12.65 ng·m−3,平均浓度(9.35±1.90)ng·m−3,颗粒态OPEs总浓度3.05—5.82 ng·m−3,平均浓度(4.18±1.56)ng·m−3. OPEs单体在空气中的含量分布不均,含量较多的是TCIPP、TCEP、TNBP. 与TCIPP、TNBP和TCEP相比,室内空气中TDCIPP、TPHP、TMPP通常含量较低,除使用量较少外,可能还与其较低的蒸气压及较高的Koa值有关[37].

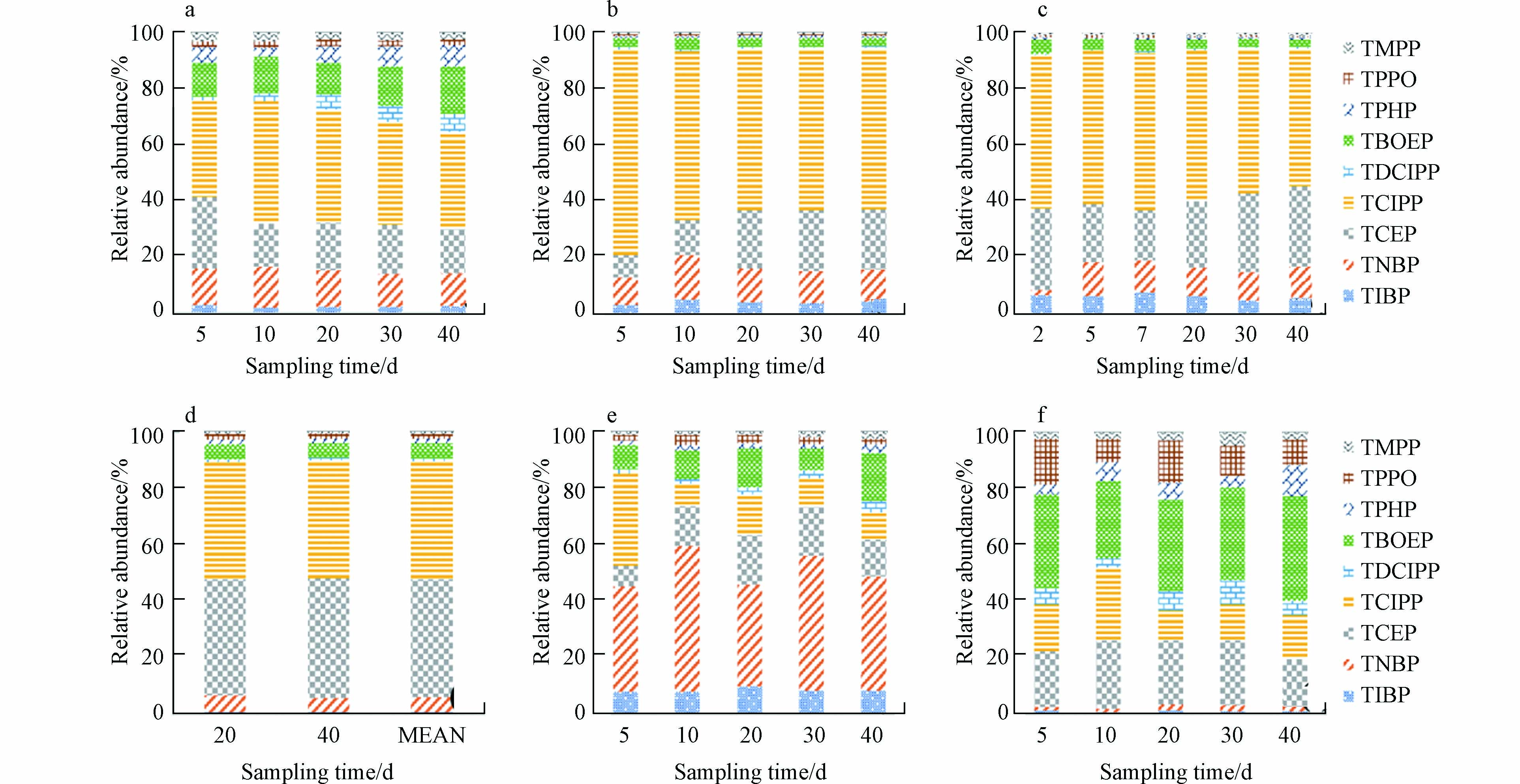

不同采样方式OPEs组成如图1所示. 从图1可见,PDMS和WB的OPEs组成十分相似,和PUF组成略有不同,与LDPE也存在明显差异,同时显著区别于主动测得的气态和颗粒态OPEs的组成. 4种被动采样OPEs均以TCIPP的含量最高(40%—70%),TCEP和TNBP次之. 空气中的OPEs包括气态和颗粒态两种状态[6,9]. 主动PUF(气态)中TNBP的组成在(40%—50%),TCEP、TCIPP和TBOEP在(8%—20%);颗粒物中TCEP和TBOEP含量最高. 四种被动采样材料中OPE的组成介于主动气态和颗粒态之间,说明被动采样除了采集气态OPEs外还可以采集到少量颗粒态OPEs,特别是LDPE中低挥发性的OPEs组成更高.

-

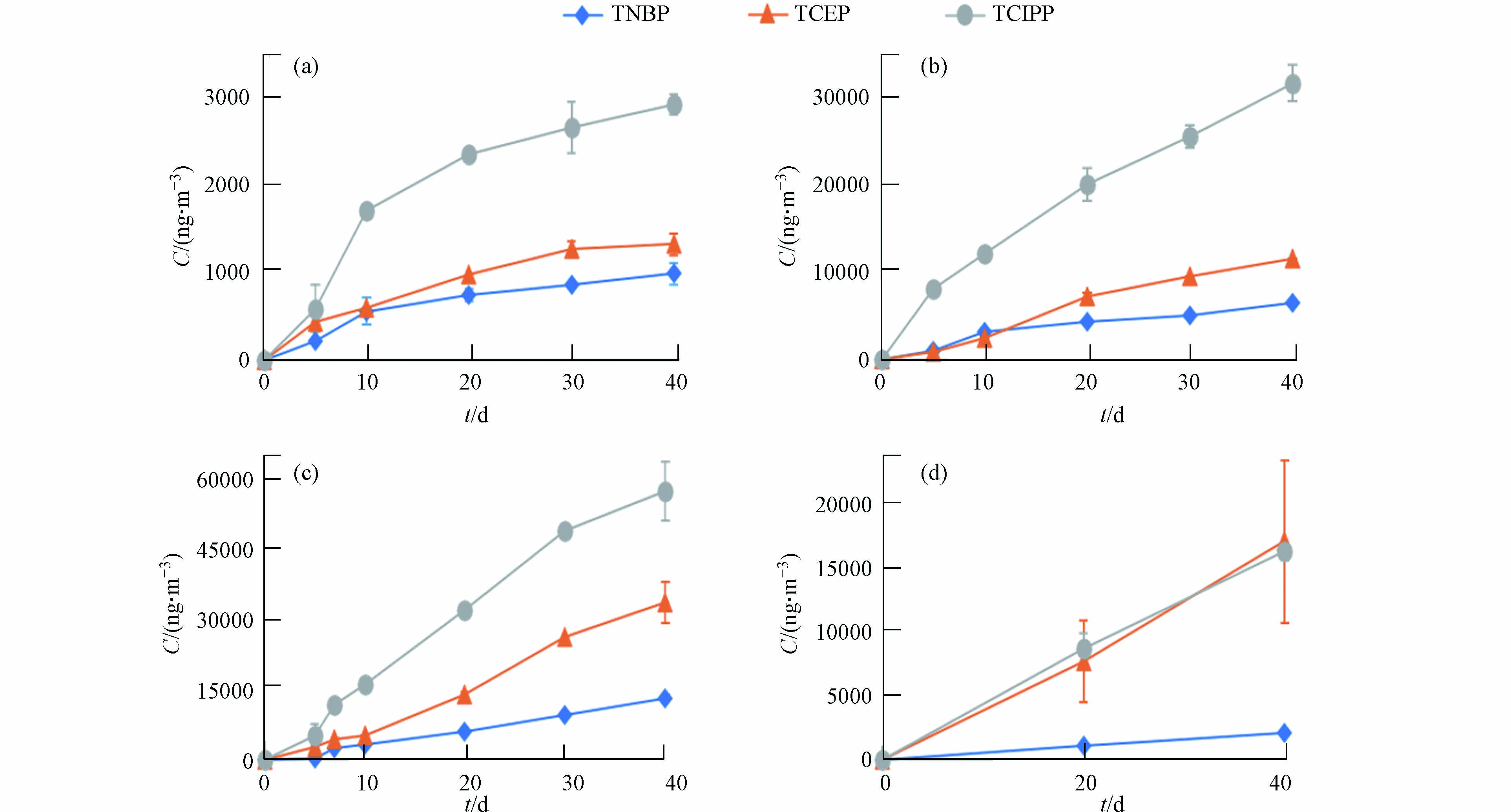

LDPE、PDMS、WB、PUF 等4种被动采样材料上OPEs的单位面积(表面积)含量随着时间的增加而增加(图2). 以TNBP、TCEP、TCIPP和TPHP为例:LDPE在采样0—20 d OPEs浓度呈线性增长,20 d后LDPE对部分OPEs(如TCIPP等)的吸附接近饱和,进入曲线增长期;PDMS、WB及PUF在采样的0—40 d时,OPEs含量均呈线性增长,说明40 d内未达到吸附饱和. 研究结果表明以LDPE为采样介质,OPEs的采样时间应在20 d以内;以PDMS、WB和PUF为OPEs的采样介质,采样时间可长达40 d,甚至更长,适合作为中长期被动采样材料. 相同时间内LDPE对OPEs的采样量显著低于WB、PDMS、PUF,约为其它3种介质的十分之一.

Okeme等[27]利用PDMS胸牌作为被动采样器采集SVOCs,发现32 d内每种化合物的采样都是线性的,与本研究结论相似. 此外,Okeme等[30]还利用PDMS和PUF对加拿大室内阻燃剂和增塑剂的研究也发现50 d内所有化合物的吸附均是线性的,唯一的例外是PUF中TPHP为非线性吸附.

-

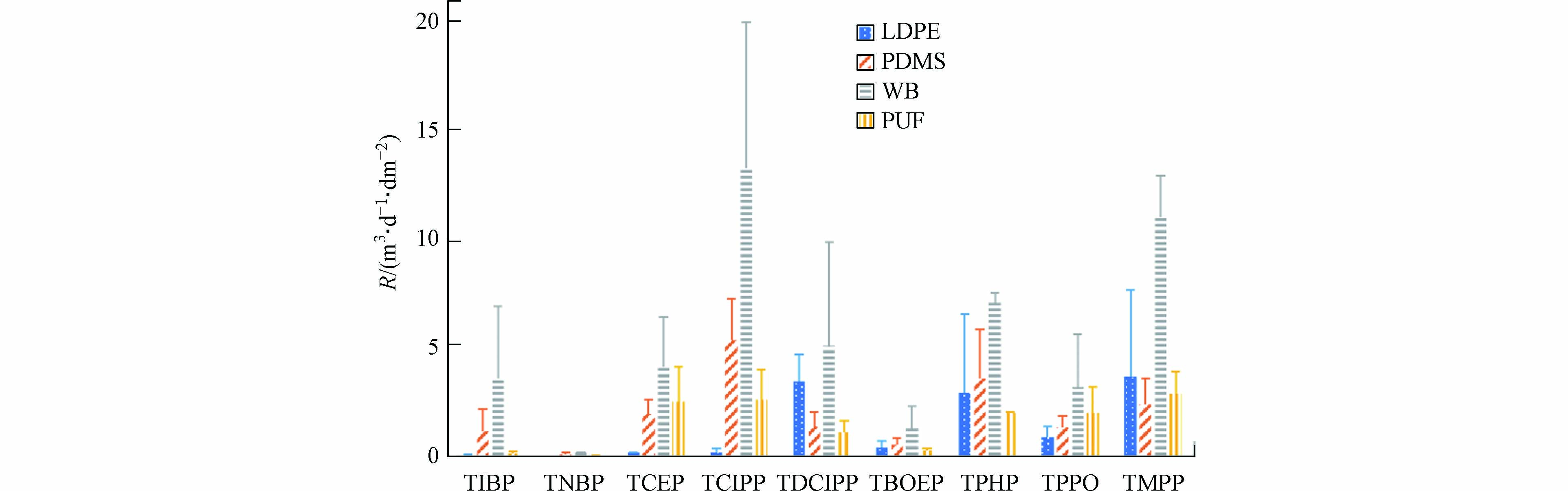

4种被动采样介质对OPEs的单位面积采样速率如图3所示. LDPE、PDMS、WB和PUF的平均采样速率分别为(1.3±1.5)m3·d−1·dm−2、(2.0±1.6)m3·d−1·dm−2、(5.4±4.3)m3·d−1·dm−2和(1.5±1.1)m3·d−1·dm−2. 总体来看,采样速率为WB >> PDMS > PUF ≈ LDPE. WB对OPEs的采样速率远大于其他介质,可能的原因包括材料性质和立体结构差异. 虽然PDMS和硅胶手环都采用硅胶材质,但其工艺和外观存在区别. 此外,PUF为圆盘状,水平放置,且有保护罩;LDPE、PDMS为片状,悬挂采样;WB为立体环状,悬挂采样. 立体环状结构可能增加了WB表面与室内空气的接触量,从而一定程度上增大其采样速率. 此外,污染物浓度、颗粒物浓度、温度和通风等都会影响被动采样速率.[34,38-39]

Okeme等的研究显示, PDMS对室内邻苯二甲酸酯(PAEs)及溴代阻燃剂(BFRs)的采样速率为(0.8±0.4)m3·d−1·dm−2 [34];PDMS和PUF对室内BFRs和OPEs的采样速率分别为(1.5±1.1)m3·d−1·dm−2、(0.90±0.60)m3·d−1·dm-2[30],与本实验结果接近. 本研究中WB对于OPEs的采样速率远大于其他介质,PDMS的采样速率大于PUF. WB由于环状外形原因,可能截留更多颗粒物或降尘,导致其采样速率较大. LDPE对TDCIPP、TPHP和TMPP的采样效果较好,PUF和PDMS对TIBP、TNBP、TCEP和TCIPP的采样效果较好.

-

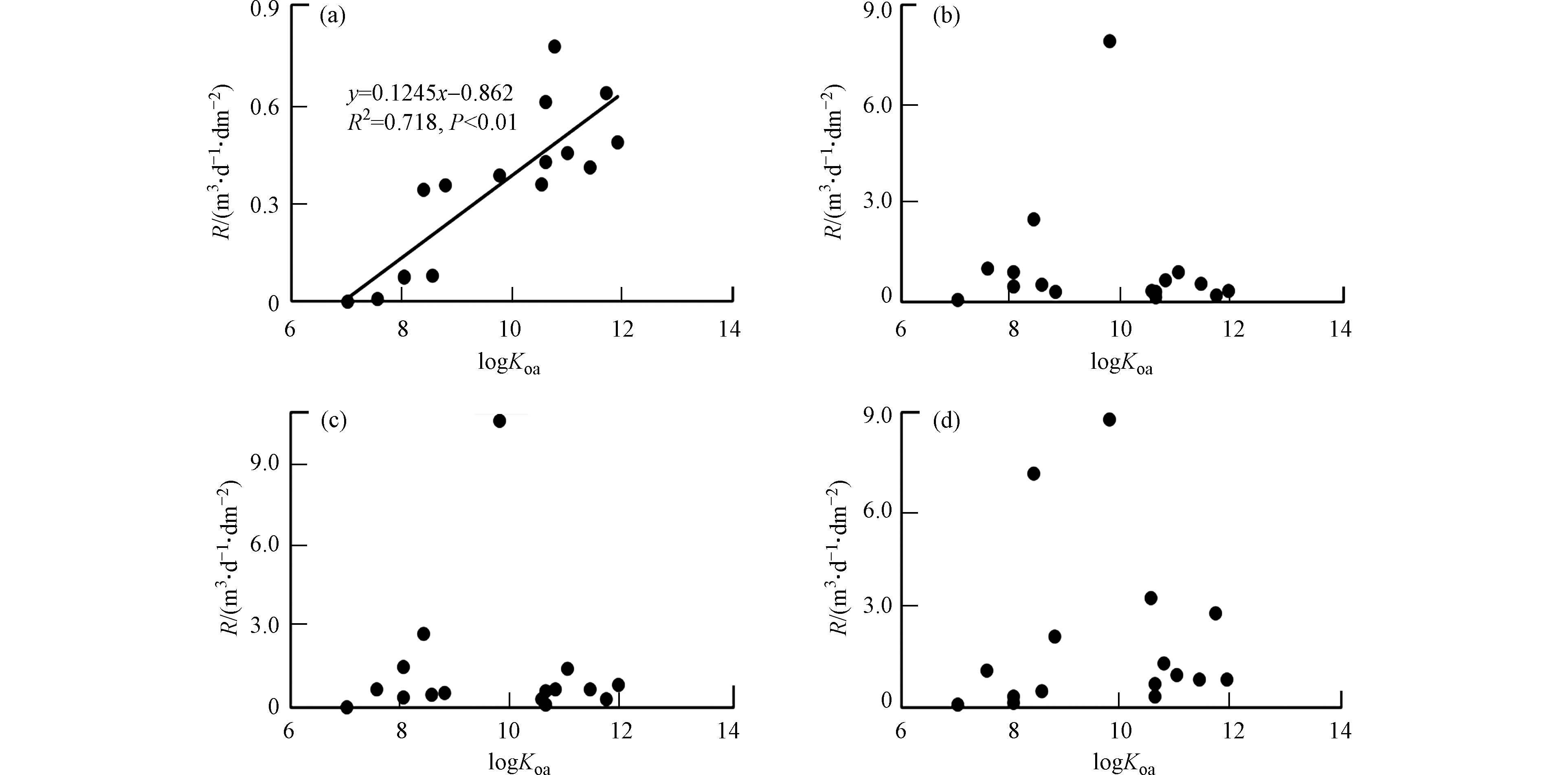

化合物在气相和颗粒相上的分配与其lgKoa相关. 本文考察了4种材料OPEs的采样速率与其Koa的相关性(图4). LDPE的采样速率与OPEs的Koa呈显著正相关(P<0.01). Koa越大,化合物越容易吸附到颗粒物上. 由于LDPE采样容积较小,其所采集的OPEs中,颗粒态OPEs的占比相对较高. 这一结论与LDPE组成中高Koa的OPE单体含量较高的结果一致. WB、PDMS和PUF中OPEs的采样速率与其Koa无显著相关,说明3种材料可能不仅只吸附气态OPEs. 研究结果表明,WB、PDMS、PUF相比LDPE更适合作为室内气态OPEs的采样材料. 同时为了尽量防止颗粒物影响,需增加防尘罩.

Wania和Shunthirasingham研究显示LDPE的采样速率与化合物Koa呈正相关关系[40],与本文一致. Okeme等[30]对加拿大室内研究显示PUF和PDMS的采样速率均与化合物Koa呈负相关,与本研究存在差异,这可能与两地空气中颗粒物污染状况不同有关.

-

(1)室内空气中检测出较高浓度的OPEs,主要单体为TCIPP、TCEP、TNBP.

(2)4种被动采样材料中OPEs的组成与主动气态OPEs组成存在较大差异,介于气态和颗粒态OPEs组成之间,说明被动采样会吸附空气中一定量的颗粒物.

(3)不同材料OPEs的采样速率存在显著差异. LDPE对OPEs的采样速率较小,达到平衡时间最快,适合短期采样;PUF、PDMS、WB采样速率较大,达到平衡时间较长,适合中长期采样.

(4)被动采样中颗粒物对浓度的影响不容忽视,应加强对被动采样器的防尘研究.

室内空气有机磷酸酯的聚二甲基硅氧烷(PDMS)、低密度聚乙烯(LDPE)和聚氨酯海绵(PUF)被动采样对比

Study on passive sampling of indoor air organophosphate esters using PDMS, LDPE and PUF

-

摘要: 室内有机磷酸酯(OPEs)阻燃剂的污染日益严重,但目前OPEs室内被动采样方法和采样速率研究缺乏. 本研究通过室内空气被动采样动力学实验,对比了低密度聚乙烯(LDPE)、聚二甲基硅氧烷(PDMS)、硅胶手环(WB)和聚氨酯海绵(PUF)的4种被动采样方法对室内空气9种典型OPEs的气态采样速率和采样效果. 4种被动采样对OPEs的平均采样速率为:WB((5.4±4.3) m3·d−1·dm−2)>PDMS((2.0±1.6) m3·d−1·dm−2)>PUF((1.5±1.1)m3·d−1·dm−2)≈LDPE((1.3±1.5)m3·d−1·dm−2). 4种被动采样OPEs组成与主动采样气态和颗粒态OPEs的组成均存在明显差异,说明被动采样受空气中细颗粒物的影响. LDPE的采样速率最小,但达到平衡时间较快,约20 d,可用于短期采样;而WB,PDMS,PUF达到平衡时间较长,更适合中、长期采样.Abstract: The indoor pollution of organophosphate esters (OPEs) flame retardants is becoming more and more serious. However, there is a lack of research on the passive sampling methods and rates of indoor OPEs. In this study, a sampling dynamics experiment was conducted for four passive sampling methods using low density polyethylene (LDPE), polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), silicone wristband (WB) and polyurethane foam (PUF) to investigate their sampling rates and effects of nine typical OPEs in indoor air. The average passive sampling rates of OPEs for these four sampling methods were in the order: WB ((5.4 ± 4.3) m3·d−1·dm−2) > PDMS ((2.0±1.6) m3·d−1·dm−2) > PUF ((1.5±1.1) m3·d−1·dm−2) ≈ LDPE ((1.3±1.5) m3·d−1·dm−2). The compositions of OPEs for the four sampling methods were significantly different from that of both the gaseous and particle OPEs using active air sampling, which suggested that passive sampling may be influenced by the fine particles in the air. LDPE has the lowest sampling rate but fastest equilibrium time, i.e., ~20 d, thus can be used for a short-term sampling. WB, PDMS and PUF have relatively long equilibrium time, thus are suitable for a medium- to long-term sampling.

-

Key words:

- organophosphate esters /

- passive air sampling /

- indoor air /

- sampling rate

-

-

表 1 目标物及其缩写

Table 1. Target compounds and their abbreviations

CAS 号

CAS No.英文名

English name中文名

Chinese name简写

Abbreviation126-71-6 Tri-i-propyl phosphate 磷酸三异丁酯 TIBP 126-73-8 Tri-n-butyl phosphate 磷酸三正丁酯 TNBP 115-96-8 Tris(2-chloroethyl) phosphate 磷酸三(2-氯乙基)酯 TCEP 13674-84-5 Tris(2-chloro-isopropyl)phosphate 磷酸三(1-氯-2-丙基)酯 TCIPP 13674-87-8 Tris(2-chloro,1-chloromethy-ethyl) phosphate 磷酸三(1,3-二氯异丙)酯 TDCIPP 78-51-3 Tris(2-butoxyethyl)phosphate 磷酸三丁氧乙酯 TBOEP 115-86-6 Triphenyl phosphate 磷酸三苯酯 TPHP 791-28-6 Triphenylphosphine oxide 三苯基氧化膦 TPPO 1330-78-5 Tricresyl phosphate 磷酸三甲苯酯 TMPP -

[1] 张月. 国内外阻燃剂市场分析 [J]. 精细与专用化学品, 2014, 22(8): 20-24. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-1100.2014.08.004 ZHANG Y. Global market analysis of flame retardant [J]. Fine and Specialty Chemicals, 2014, 22(8): 20-24(in Chinese). doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-1100.2014.08.004

[2] LUO Y L, GUO W S, NGO H H, et al. A review on the occurrence of micropollutants in the aquatic environment and their fate and removal during wastewater treatment [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2014, 473/474: 619-641. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.12.065 [3] 王晓伟, 刘景富, 阴永光. 有机磷酸酯阻燃剂污染现状与研究进展 [J]. 化学进展, 2010, 22(10): 1983-1992. WANG X W, LIU J F, YIN Y G. The pollution status and research progress on organophosphate ester flame retardants [J]. Progress in Chemistry, 2010, 22(10): 1983-1992(in Chinese).

[4] WEI G L, LI D Q, ZHUO M N, et al. Organophosphorus flame retardants and plasticizers: Sources, occurrence, toxicity and human exposure [J]. Environmental Pollution (Barking, Essex:1987), 2015, 196: 29-46. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2014.09.012 [5] XU F C, GIOVANOULIS G, van WAES S, et al. Comprehensive study of human external exposure to organophosphate flame retardants via air, dust, and hand wipes: The importance of sampling and assessment strategy [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2016, 50(14): 7752-7760. [6] 唐斌, 蔡凤珊, 王美欢, 等. 室内灰尘和空气中有机磷系阻燃剂和塑化剂的赋存、分配和暴露风险评估[C]. 2020中国环境科学学会科学技术年会论文集(第一卷), 2020: 1078-1084. TANG B, CAI F S, WANG M H, et al. Storage, distribution and exposure risk assessment of organophosphorus flame retardants and plasticizers in indoor dust and air[C]. Proceedings of 2020 CSES Annual Conference on Environmental Science and Technology (Part Ⅰ), 2020: 1078-1084(in Chinese).

[7] 印红玲, 李世平, 叶芝祥, 等. 成都市大气PM2.5中有机磷阻燃剂的污染水平及来源 [J]. 环境科学, 2015, 36(10): 3566-3572. YIN H L, LI S P, YE Z X, et al. Pollution level and sources of organic phosphorus esters in airborne PM2.5 in Chengdu city [J]. Environmental Science, 2015, 36(10): 3566-3572(in Chinese).

[8] ZHANG Z H, XU Y, WANG Y, et al. Occurrence and distribution of organophosphate flame retardants in the typical soil profiles of the Tibetan Plateau, China [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2022, 807: 150519. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150519 [9] 张洛红, 朱钰, 李宗睿, 等. 有机磷酸酯污染现状及其生物富集和生物转化研究进展 [J]. 环境化学, 2021, 40(8): 2355-2370. doi: 10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2020121701 ZHANG L H, ZHU Y, LI Z R, et al. Pollution status, bioaccumulation and biotransformation of organophosphate esters: A review [J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2021, 40(8): 2355-2370(in Chinese). doi: 10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2020121701

[10] LI J H, ZHAO L M, LETCHER R J, et al. A review on organophosphate Ester (OPE) flame retardants and plasticizers in foodstuffs: Levels, distribution, human dietary exposure, and future directions [J]. Environment International, 2019, 127: 35-51. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.03.009 [11] BUTT C M, CONGLETON J, HOFFMAN K, et al. Metabolites of organophosphate flame retardants and 2-ethylhexyl tetrabromobenzoate in urine from paired mothers and toddlers [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2014, 48(17): 10432-10438. [12] HE C, TOMS L L, THAI P, et al. Urinary metabolites of organophosphate esters: Concentrations and age trends in Australian children [J]. Environment International, 2018, 111: 124-130. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.11.019 [13] BOYLE M, BUCKLEY J P, QUIRÓS-ALCALÁ L. Associations between urinary organophosphate ester metabolites and measures of adiposity among US children and adults: NHANES 2013-2014 [J]. Environment International, 2019, 127: 754-763. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.03.055 [14] GAO D T, YANG J, BEKELE T G, et al. Organophosphate esters in human serum in Bohai Bay, North China [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 2020, 27(3): 2721-2729. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-07204-5 [15] HOU M M, SHI Y L, JIN Q, et al. Organophosphate esters and their metabolites in paired human whole blood, serum, and urine as biomarkers of exposure [J]. Environment International, 2020, 139: 105698. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105698 [16] WANG X L, LIU Q J, ZHONG W, et al. Estimating renal and hepatic clearance rates of organophosphate esters in humans: Impacts of intrinsic metabolism and binding affinity with plasma proteins [J]. Environment International, 2020, 134: 105321. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105321 [17] HE M J, LU J F, MA J Y, et al. Organophosphate esters and phthalate esters in human hair from rural and urban areas, Chongqing, China: Concentrations, composition profiles and sources in comparison to street dust [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2018, 237: 143-153. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.02.040 [18] KUCHARSKA A, CEQUIER E, THOMSEN C, et al. Assessment of human hair as an indicator of exposure to organophosphate flame retardants. Case study on a Norwegian mother-child cohort [J]. Environment International, 2015, 83: 50-57. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.05.015 [19] LIU L Y, HE K, HITES R A, et al. Hair and nails as noninvasive biomarkers of human exposure to brominated and organophosphate flame retardants [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2016, 50(6): 3065-3073. [20] 陈静怡, 胡华丽, 冯磊, 等. 有机磷酸酯阻燃剂生物毒性效应及生物降解的研究进展 [J]. 生物学教学, 2020, 45(7): 2-4. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-7549.2020.07.001 CHEN J Y, HU H L, FENG L, et al. Research Progress on biological toxicity and biodegradation of organic phosphate flame retardants [J]. Biology Teaching, 2020, 45(7): 2-4(in Chinese). doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-7549.2020.07.001

[21] van der VEEN I, de BOER J. Phosphorus flame retardants: Properties, production, environmental occurrence, toxicity and analysis [J]. Chemosphere, 2012, 88(10): 1119-1153. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.03.067 [22] BEKELE T G, ZHAO H X, WANG Q Z. Tissue distribution and bioaccumulation of organophosphate esters in wild marine fish from Laizhou Bay, North China: Implications of human exposure via fish consumption [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2021, 401: 123410. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123410 [23] ZHANG Q, LU M Y, DONG X W, et al. Potential estrogenic effects of phosphorus-containing flame retardants [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2014, 48(12): 6995-7001. [24] BEHL M, HSIEH J H, SHAFER T J, et al. Use of alternative assays to identify and prioritize organophosphorus flame retardants for potential developmental and neurotoxicity [J]. Neurotoxicology and Teratology, 2015, 52: 181-193. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2015.09.003 [25] TAO F, ABDALLAH M A, HARRAD S. Emerging and legacy flame retardants in UK indoor air and dust: Evidence for replacement of PBDEs by emerging flame retardants? [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2016, 50(23): 13052-13061. [26] VYKOUKALOVÁ M, VENIER M, VOJTA Š, et al. Organophosphate esters flame retardants in the indoor environment [J]. Environment International, 2017, 106: 97-104. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.05.020 [27] OKEME J O, NGUYEN L V, LORENZO M, et al. Polydimethylsiloxane (silicone rubber) brooch as a personal passive air sampler for semi-volatile organic compounds [J]. Chemosphere, 2018, 208: 1002-1007. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.05.196 [28] WANG S R, ROMANAK K A, STUBBINGS W A, et al. Silicone wristbands integrate dermal and inhalation exposures to semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs) [J]. Environment International, 2019, 132: 105104. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105104 [29] O'CONNELL S G, KINCL L D, ANDERSON K A. Silicone wristbands as personal passive samplers [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2014, 48(6): 3327-3335. [30] OKEME J O, YANG C Q, ABDOLLAHI A, et al. Passive air sampling of flame retardants and plasticizers in Canadian homes using PDMS, XAD-coated PDMS and PUF samplers [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2018, 239: 109-117. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.03.103 [31] 裴婕. 以低密度聚乙烯膜(LDPE)为吸附相的被动采样技术对新型卤代阻燃剂的LDPE-水平衡分配系数的应用[D]. 广州: 暨南大学, 2019. PEI J. Application of passive sampling technique with low-density polyethylene (LDPE) as sorbent phase for determining of LDPE-water partition coefficients for novel halogenated flame retardants[D]. Guangzhou: Jinan University, 2019(in Chinese).

[32] 叶雪莹. PVC管材源微塑料中邻苯二甲酸酯的释放行为研究[D]. 杭州: 浙江工业大学, 2020. YE X Y. The release behavior of phthalates from PVC pipe microplastics[D]. Hangzhou: Zhejiang University of Technology, 2020(in Chinese).

[33] SAINI A, OKEME J O, GOOSEY E, et al. Calibration of two passive air samplers for monitoring phthalates and brominated flame-retardants in indoor air [J]. Chemosphere, 2015, 137: 166-173. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.06.099 [34] OKEME J O, SAINI A, YANG C Q, et al. Calibration of polydimethylsiloxane and XAD-Pocket passive air samplers (PAS) for measuring gas- and particle-phase SVOCs [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2016, 143: 202-208. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.08.023 [35] 闫振飞, 廖伟, 冯承莲, 等. 典型有机磷酸酯阻燃剂分析方法研究进展 [J]. 生态毒理学报, 2020, 15(1): 94-108. doi: 10.7524/AJE.1673-5897.20190509002 YAN Z F, LIAO W, FENG C L, et al. Research progress on analysis methods of typical organophosphate esters(OPEs) flame retardants [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2020, 15(1): 94-108(in Chinese). doi: 10.7524/AJE.1673-5897.20190509002

[36] 张文萍, 张振飞, 郭昌胜, 等. 环太湖河流及湖体中有机磷酸酯的污染特征和风险评估 [J]. 环境科学, 2021, 42(4): 1801-1810. doi: 10.13227/j.hjkx.202008266 ZHANG W P, ZHANG Z F, GUO C S, et al. Pollution characteristics and risk assessment of organophosphate esters in rivers and water body around Taihu Lake [J]. Environmental Science, 2021, 42(4): 1801-1810(in Chinese). doi: 10.13227/j.hjkx.202008266

[37] WANG Y, YAO Y M, HAN X X, et al. Organophosphate di- and tri-esters in indoor and outdoor dust from China and its implications for human exposure [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 700: 134502. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134502 [38] PERSOON C, HORNBUCKLE K C. Calculation of passive sampling rates from both native PCBs and depuration compounds in indoor and outdoor environments [J]. Chemosphere, 2009, 74(7): 917-923. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.10.011 [39] BOHLIN P, AUDY O, ŠKRDLÍKOVÁ L, et al. Evaluation and guidelines for using polyurethane foam (PUF) passive air samplers in double-dome Chambers to assess semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs) in non-industrial indoor environments [J]. Environmental Science. Processes & Impacts, 2014, 16(11): 2617-2626. [40] WANIA F, SHUNTHIRASINGHAM C. Passive air sampling for semi-volatile organic chemicals [J]. Environmental Science. Processes & Impacts, 2020, 22(10): 1925-2002. -

下载:

下载: