-

2014年原生态环境部和自然资源部发布的《全国土壤污染状况调查公报》显示[1],在重点调查的690家污染企业用地和周边环境中,36.3%属于超标点位,其中一些典型企业(如石油炼化、焦化、电镀和制革等)被列为重点监管企业. 近40年来,我国的石油化工行业迅速发展,2010年产值规模跃居世界第二,其化工产值规模远超美国,位居世界第一,成为世界石油和化工大国[2]. 胜利油田作为我国石油化工的重要基地,其石油年产量为

2340 万t,炼油厂炼油能力达每年1800 万t. 目前,多个研究报道表明,石油炼化和下游化工已被认定为挥发性有机物(VOCs)排放的典型区域[3 − 9]. 苯系物(BTEXs)是VOCs中的一类特征污染物,2017年,世卫组织国际癌症机构将BTEXs列入致癌清单中,其中苯属于Ⅰ类致癌物质,乙苯和苯乙烯为Ⅱ类致癌物质,甲苯和二甲苯为Ⅲ类致癌物质. 苯系物也已被我国列入污染物优先控制名单中[10].研究表明,石油冶炼的高温工艺可以加速BTEXs的产生与排放[11],占工业来源总排放量的18.1%—34.5%[12],进而导致BTEXs被释放进入周边环境介质中[13 − 17]. 由于苯系物是二次气溶胶的重要前体[18],对臭氧的生成具有重要贡献[19],工业或生活中产生的苯系物释放到环境中,容易导致城市光化学烟雾,造成二次污染[20]. 石油冶炼厂区的污染状况会直接影响职工和周边居民健康状况. 苯系物具有“三致”效应,对人体有较为直接的危害性,且难以预防. BTEXs可通过多种暴露途径进入人体中,会迅速分布于各个组织器官中,主要累积在脂肪中,可通过细胞色素P-450IIEI在肝脏组织中代谢[21],其神经毒性和遗传毒性会对人体的皮肤黏膜、中枢神经和造血功能产生损害. 有研究表明,敏感人群尤其是儿童,长期暴露于苯系物污染的环境中,会增加哮喘患病率[22],甚至引起再生障碍性贫血和白血病[23] 等疾病.

自2010年始,我国学者开始重点关注典型石油冶炼企业包括苯系物在内的大气中挥发性有机物污染特征[24 − 26]。有研究表明,在油品运输储存,生产加工等冶炼装置过程中,存在一定的挥发性有毒污染物污染及健康风险[27]. 以往研究多集中在大气环境介质中,针对不同环境介质(大气和土壤)以及炼油过程中不同子功能区中BTEXs的分布、健康风险评估缺乏系统性研究,同时尚不明确石油冶炼过程释放的BTEXs是否对周边环境存在区域传输. 因此,有必要对典型石油冶炼工业区不同环境介质中BTEXs的暴露水平进行系统研究,明确其对职业人群和周边居民带来的健康风险.

本文研究了典型石油冶炼企业炼油过程不同功能区BTEXs污染水平和组成分布特征,通过计算暴露量,明确该区域不同人群对BTEXs的主要暴露途径,评估BTEXs可能存在的健康风险. 希望为典型工业区的污染控制和周边居民健康管理提供参考,对预防环境污染事件的发生也具有重要意义.

-

苯(Benzene)、甲苯(Toluene)、乙苯(Ethylbenzene)、间+对二甲苯(p,m -xylene)、苯乙烯(Styrene)、邻二甲苯(O-xylene)和异丙苯(Cumene)及内标物(氟苯)标准品(纯度>99%)由德国Sigma公司提供;色谱纯(99.9%)甲醇由德国Sigma提供. 氯化钠为优级纯,购自国药集团;水为超纯水.

-

胜利油田位于山东省东营市,是中国第二大油田,年产量为

2340 万t,其炼油厂年炼油能力1800 万t. 厂区主要有常减压蒸馏、催化裂化、催化重整、加氢精制和芳烃抽提等工艺装置. 本研究针对石油冶炼场地不同的功能分区(冶炼区、产品储存区、原油储存区、办公区)及周边居民区,同时以不涉及石油炼化等工业区的山东省莱阳市中心为对照区开展样品采集工作,共有18个采样位点,具体研究区域采样点分布如图1所示.大气样品:用采样泵以1 mL·min−1的速度通过Tenax吸附管抽取大气,持续采集24 h,使得大气样品中苯系物捕集浓缩至吸附管上. 所有吸附管在冷却容器中保存运输,在4 ℃下保存,48 h完成分析.

土壤样品:采用梅花形采样法采集土壤. 每个采样地选择50 m×50 m的地块,在地块的中心点取1个点,再在周围取4个点,使用不锈钢铲在每个点分别采集表层土(深度0—20 cm)1 kg;将5个点样品混匀,用四分法取其中1 kg的土壤放入棕色玻璃容器中,密封,4 ℃温度下带回实验室.

-

大气样品采用热解析气相色谱-质谱法(TD-GC-MS)[28]. 采用顶空气相色谱-质谱(HS-GC-MS)对土壤样品进行分析[29].

-

苯系物样品的定性和定量分析采用Agilent GC 7890A-MSD5975C 气相色谱质谱联用仪;DB—624色谱柱(30 m ×0.32 mm,膜厚1.8 μm;Agilent公司),色谱设置条件为:进样口温度200 ℃; 载气:氦气;分流比:5:1;柱流量(恒流模式):2 mL·min−1;升温程序: 初始温度35 ℃,保持5 min,以6 ℃·min−1升温到170 ℃保持2 min,12 ℃·min−1升温至200 ℃保持1 min离子化能量:70 eV;接口温度:280 ℃. 表1总结了目标化合物参数.

-

为了减少BTEXs的污染,保证样品采集和分析过程中数据的准确性,采取了一系列严格的控制措施:(1)所有的试管在使用前都要用甲醇清洗. (2)在取样过程中,制备样品的现场空白. (3)在样本分析过程中,每5个样本设置1个程序空白. BTEXs的检测限(LODs)和定量限(LOQs)分别是添加了目标化合物的程序空白样品(n=7)的信号标准差的3倍和10倍. 空气和土壤样品的LODs值分别为0.67—0.92 ng·mL−1、0.04—0.91 ng·g−1. 空气和土壤LOQs分别为2.22—3.05 ng·mL−1、0.14—3.03 ng·g−1. 空气和土壤样品中BTEX的回收率分别为85%—96%、84—97%.

-

本研究采用美国环境保护署提出健康风险评价方法(USEPA,2009年). 根据实际环境浓度和相关参数计算暴露剂量;进而采用污染物的毒性参数(见表2)计算健康风险指数,评估其非致癌风险和致癌风险.

吸入和土壤摄入的暴露剂量计算公式如下.

其中,ECinh(mg·kg−1·d−1)为吸入的暴露剂量;ECing(mg·kg−1·d−1)为口服摄入的暴露剂量;CA(mg·m−3)为空气中污染物的浓度;CS(mg·kg−1)为土壤中污染物的浓度;IR为呼吸频率(20 m3·h−1);SR为吞咽速率(10−6 kg·d−1);ET为暴露时间(8 h·d−1);EF为暴露频率(300 d·a−1);ED为暴露时间(30 a);BW为体重(70 kg);AT为平均时间(40 a ×300 d).

非致癌危险商(HQs)计算公式如下.

其中,HQ为非致癌风险危害商值;Rfc为单位吸入非致癌风险浓度(mg·m−3);RfD为经口摄入参考剂量(mg·.kg−1·d−1). HI为非致癌风险危害指数.

致癌风险(Risk)计算公式如下.

其中,Riskinh是吸入的致癌风险;Risking是口服摄入的致癌风险,IUR是单位呼吸致癌风险浓度;SF是经口摄入致癌因子,见表2.

对于非致癌风险的健康影响,若HI≤1不存在非致癌风险;HI>1,表明污染物对人体具有非致癌风险危害. 对于致癌风险的健康影响,Risk<1×10−6表示致癌风险可忽略不计;Risk>1×10−4表明具有较高的致癌风险;1×10−6<Risk<1×10−4表明具有潜在的致癌风险.

-

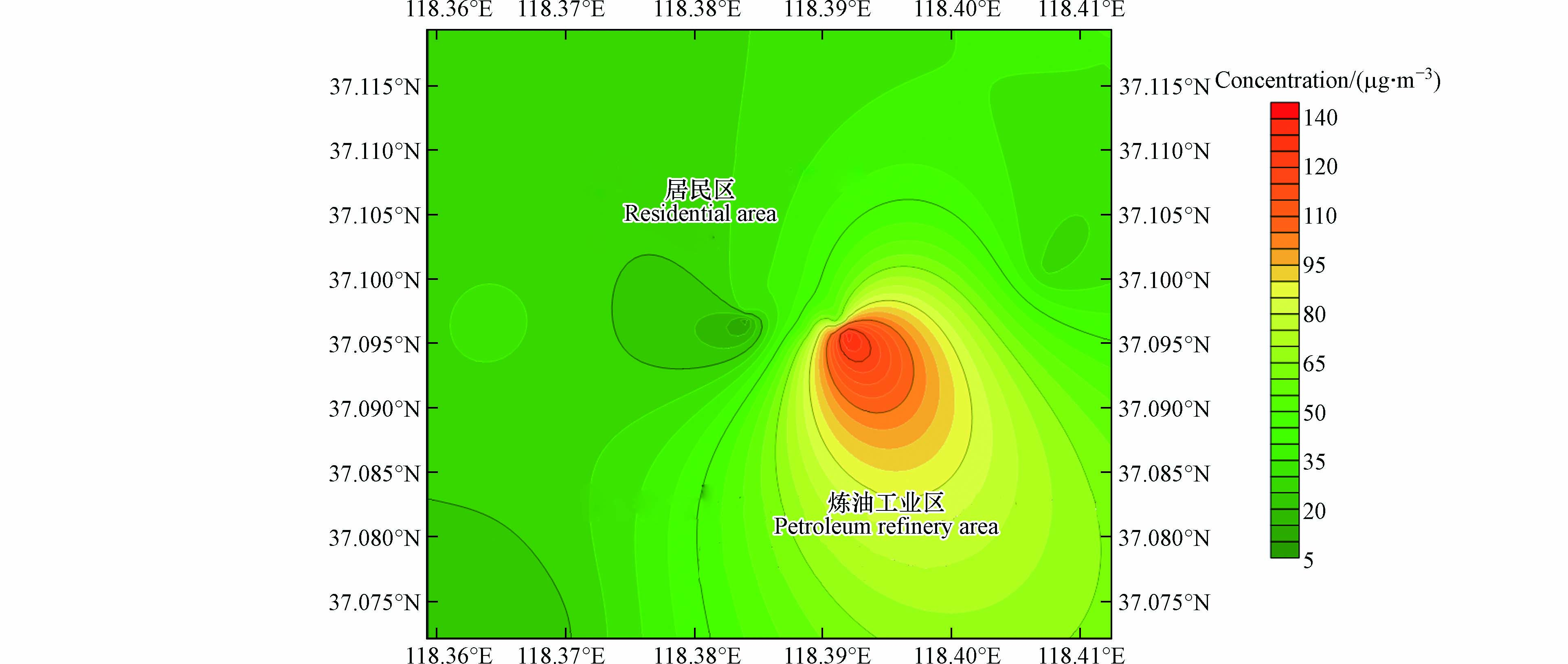

炼油工业区大气样品8种BTEXs均被检出,除乙苯检出率(df)为87.5%,苯、甲苯、间对二甲苯等其余7种目标化合物的检出率均为100%. 炼油工业区∑BTEXs的平均浓度(49.2 μg·m−3)分别是周边居民区(28.9 μg·m−3)和对照区(18.3 μg·m−3)的1.7倍和2.6倍. 采用反距离加权(IDW)插值模型,从有限点位得到了炼油区及周边地区大气BTEXs的连续性分布. 从图2可以看出,大气BTEXs浓度从炼油区到周边地区呈现逐渐递减的趋势,且炼油工业区表面风向对大气BTEXs传输具有一定的影响.

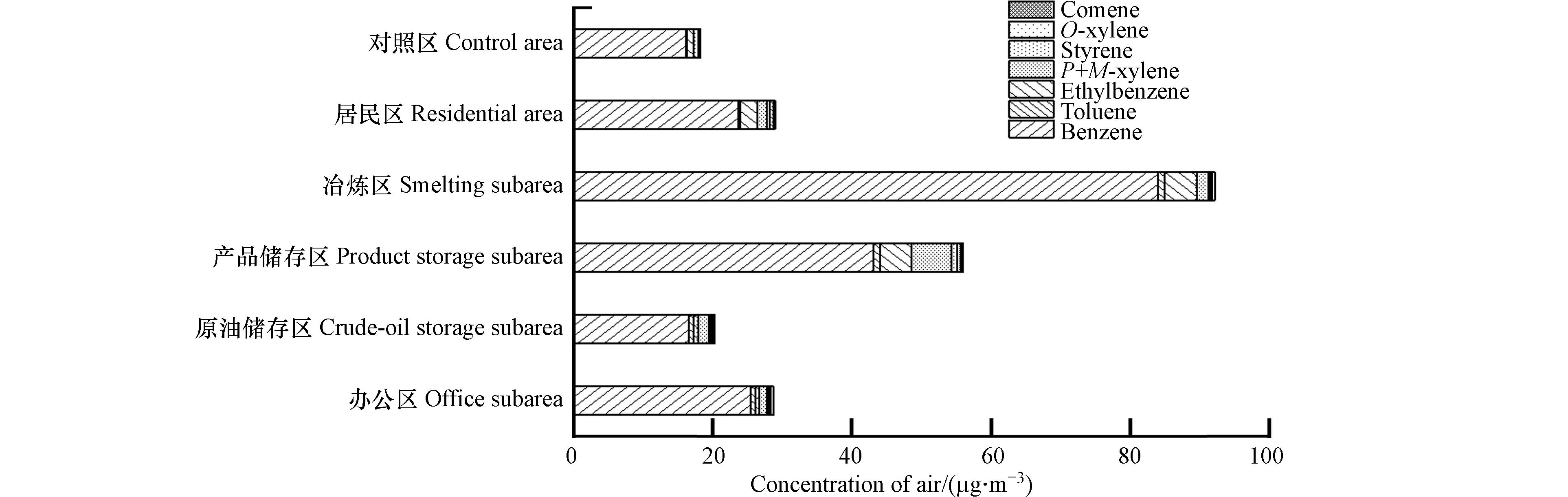

在不同功能分区中,如图3所示,冶炼区(92.1 μg·m−3)的平均浓度最高,分别是产品储存区(56.0 μg·m−3)、办公区(28.0 μg·m−3)和原油储存区(20.3 μg·m−3)的1.6—4.5倍. 为评估本研究区大气BTEXs污染水平,分别与其他化工区域进行比较. 结果表明,本研究炼油工业区域大气样品中∑BTEXs平均浓度与中国重庆典型工业区周边大气中浓度(36.3 μg·m−3)相当[28],高于土耳其阿利亚加湾高度工业化地区(15.1 μg·m−3)[31]. 炼油工业区大气中BTEXs各组分浓度排序为:苯>乙苯>甲苯>对+间二甲苯>邻二甲苯>苯乙烯>异丙苯. 在炼油区域大气中总苯系物(∑BTEXs)组成中苯(平均浓度=45 μg·m−3)的贡献最大,占比可达83%,分析可能的原因是在石油催化、重整和分离过程中容易形成高浓度的苯. 同时苯的挥发性高于其他BTEXs,使得更容易挥发进入大气. 与其他工业区对比,本研究区苯的浓度高于土耳其化工园区(2.7 μg·m−3)和中国重庆某化工园区(0.3 μg·m−3). 值得注意的是,甲苯(0.8 μg·m−3)仅占∑BTEXs的1.2%,不同于其他工业区的文献报道,例如,在中国重庆某石化地区甲苯占比可达19.4%和23% [28]. 在本研究工业区的周边居民区大气中苯的含量占81%,与炼油区域趋势相同,表明炼油行业释放的BTEXs对周围区域具有一定的影响. 此外,在对照区中苯的贡献率为88%,该区域属于城区,周围无化工企业,可能其他人为活动(如汽车尾气和建筑涂料使用)也会导致向环境释放BTEXs.

-

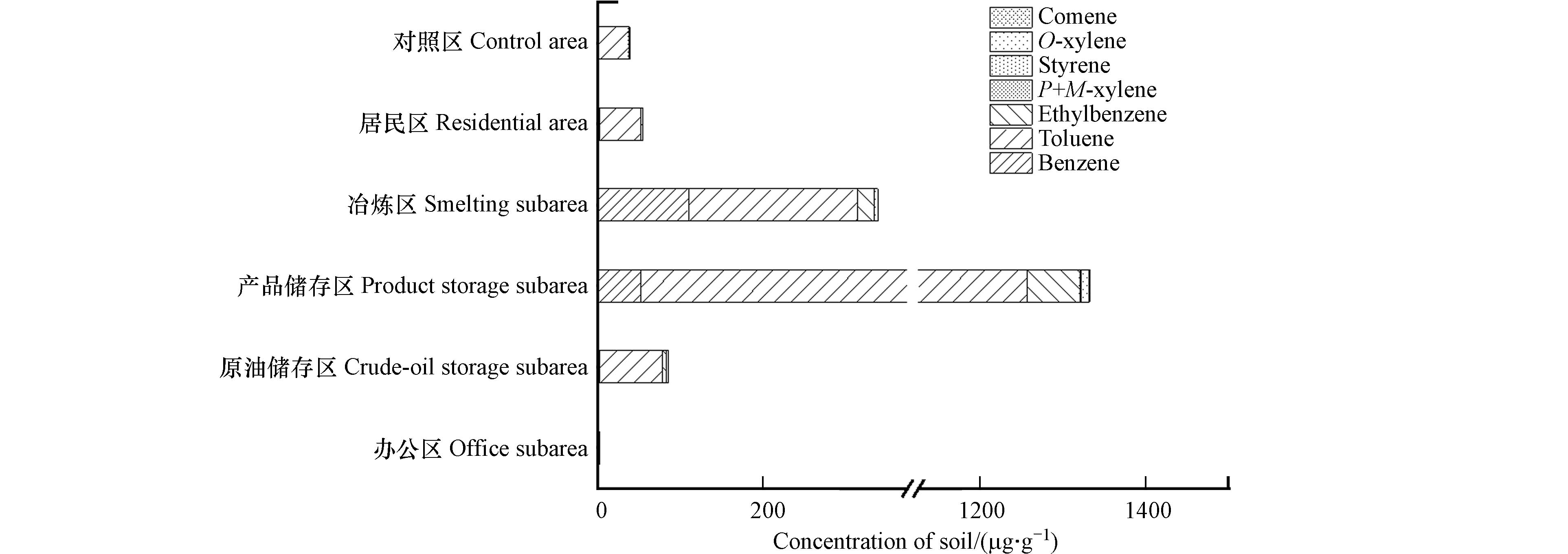

炼油工业区土壤样品中苯、甲苯、苯乙烯和异丙苯均100%被检出,而乙苯(df=50%)、间+对二甲苯和苯乙烯(df=62.5%)不同程度被检出. 炼油工业区土壤∑BTEXs的平均浓度(578.3 µg·g−1)分别是周边居民区(54.8 µg·g−1)和对照区(38.9 µg·g−1)的10倍和14倍. 同样,也采用反距离加权(IDW)插值模型,从有限点位得到了炼油区及周边地区土壤BTEXs的连续性分布(见图4). 与大气相比,产品储存区(1.3×103 µg·g−1)和冶炼区(557 µg·g−1)两个点位土壤中目标物的浓度最高,原油储存区(85.0 µg·g−1)和办公区(1.90 µg·g−1)的浓度水平较低,说明土壤中BTEXs的水平扩散能力较小. 见图5. 本研究区BTEXs的平均浓度略低于某除草剂生产企业表层土壤BTEXs的平均浓度(789 µg·g−1)[32],但明显高于河北某农药企业(0.7—32 µg·g−1)[33]和江苏南通某化工园区土壤BTEXs含量(1.5 µg·g−1)[34].

炼油区土壤中BTEXs各组分浓度排序为:甲苯>苯>乙苯>苯乙烯>对+间二甲苯>邻二甲苯>异丙苯(如图5所示). 土壤BTEXs的组成特征与大气有所不同,甲苯(471 µg·g−1)在炼油区贡献率最大,占比高达85%,其次是苯(54.8 µg·g−1),占比10%,而乙苯 (24.9 µg·g−1)仅占4%.

炼油工业区土壤甲苯平均浓度(471 µg·g−1)比中国南通化学工业园区[35]和河北省某除草剂生产工厂[33](6.6×10−3µg·g−1和16.3 µg·g−1)高2—4个数量级,说明不同的污染场地,BTEXs组成特征存在一定的差异. 同时在周边居民区和对照区也发现同样趋势,居民区土壤甲苯、苯和乙苯分别占93%、4.6%和2.3%,对照区甲苯、苯和乙苯分别占93%、4.4%和1.4%. 挥发是土壤环境中BTEXs最重要的迁移转化方式,表层土壤附着的BTEXs能够通过挥发作用逸散到大气中,同时BTEXs的挥发速率与自身土壤环境和理化性质有关. 有学者 [36]报道了苯系物的挥发速率常数与蒸汽压之间呈线性正相关,土壤BTEXs单个污染物挥发速率表现为:苯>甲苯>二甲苯>乙苯. 因此,炼油工业区土壤环境中甲苯占比高,而大气环境中苯占比较大,可能与二者的挥发速率有关. 另一方面,根据Estimation program Interface(EPI)suite 4.1,土壤中甲苯的半衰期低于苯,然而甲苯浓度高于苯,说明其除了充当石油冶炼的有机溶剂大量使用之外,土壤中的甲苯可能还存在其他来源,如固体(油渣)废物处理过程中的泄露等.

-

根据公式计算,呼吸摄入和土壤口服摄入∑BTEXs的平均日暴露剂量分别为8.4×10−2 mg·kg−1·d−1 (5.6×10−4—1.5×10−1 mg·kg−1·d−1)和4.8×10−3 mg·kg−1·d−1(4.2×10−7—8.6×10−3 mg·kg−1·d−1),呼吸摄入暴露途径的BTEXs平均日暴露剂量比口服摄入暴露途径高约一个数量级,表明对BTEXs主要暴露方式为呼吸摄入. 随后通过空气吸入和土壤口服摄入计算苯系物的平均危险商(HQ),如表3所示. 本研究区吸入平均危险商(HQs)范围为1.1×10−6—9.6×10−3,口服摄入平均危险商(HQs)范围为5.1×10−10—1.7×10−4. 经空气吸入的暴露风险结果表明,不同功能区中冶炼区(5.0×10−3)的危害指数(HI)最高,其次是产品储存区(2.4×10−3). 而经口服摄入的结果为产品储油区(4.3×10−4)最高,其次是冶炼区(1.6×10−4). BTEXs通过空气吸入的非致癌风险比口服摄入高约一个数量级. 总的来说,BTEXs通过空气吸入和土壤口服摄入两种暴露途径的健康危害指数(HIs)均小于1,无明显的非致癌风险,这表明该研究区域的非致癌风险可以忽略不计.

-

8种BTEXs中仅获得苯和乙苯的单位呼吸致癌风险浓度(IUR)和口服摄入致癌因子(SF)值,未获得其余6种相关参数. 因此,对这两种化合物进行了致癌风险评估. 就吸入暴露而言,炼油区中苯和乙苯的平均致癌风险分别为5.6×10−4和1.3×10−5,而通过口服摄入暴露,苯和乙苯的平均致癌风险分别为4.5×10−5和6.7×10−7. 在炼油区中苯的平均致癌风险远高于乙苯,且高于周边居民区和对照区.

经呼吸暴露的致癌风险计算结果发现,苯的致癌风险(1.1×10−3)冶炼区最高,其次是产品储存区(5.5×10−4),对照区(2.15×10−4)最小. 由表4可知,子功能区的致癌风险均超过了10−4,表明这些子功能区具有较高的致癌风险. 苯属于Ⅰ类致癌物质,长期暴露在该环境下可能会产生一定的健康影响,需要引起高度重视. 乙苯的致癌风险(2.4×10−6—1.3×10−5)均在可接受的范围内(10−6—10−4),具有潜在的致癌风险.

经口服摄入暴露的致癌风险结果为苯的致癌风险在产品储存区(1.0×10−4)中最高,其次是冶炼区(4.7×10−5)、原油储存区(3.2×10−5)等,其他子功能区的致癌风险均在10−6—10−4之间,表明在可接受范围内,具有潜在的致癌风险. 产品储存区(1.7×10−6)乙苯的致癌风险最高,存在潜在的致癌风险,其他功能区乙苯的致癌风险均低于10−6,无致癌风险,可以忽略不计.

-

1)典型石油炼化区不同环境介质BTEXs的组成特征为:大气中苯贡献最大,其次是乙苯和甲苯. 甲苯在土壤环境中占比最大,其次是苯.

2)大气和土壤中BTEXs浓度从石油炼化区到周边居民区呈逐渐递减趋势,且存在区域传输,说明周边区域大气受石油冶炼影响较大,而土壤环境中BTEXs水平扩散能力较小. 不同功能区中冶炼区和产品储存区BTEXs浓度明显高于其他区域;

3)典型炼油工业区BTEXs的吸入暴露量高于口服摄入,说明主要以吸入暴露为主.

4)对炼化工业区职业健康风险评估的结果显示,BTEXs的非致癌风险值均低于安全阈值(HI<1);乙苯对炼油工人产生的致癌风险可忽略,但苯的致癌风险超过可接受水平,具有较高的致癌风险.

典型炼油工业区及周边环境介质中苯系物健康风险评估

Health risk assessment of BTEXs in one typical petroleum refinery and surrounding area of China

-

摘要: 本研究考察了2021—2022年间典型炼油工业及周边区域大气和土壤样品中8种苯系物(BTEXs)(苯、甲苯、乙苯、对+间二甲苯、邻二甲苯、苯乙烯和异丙苯)的污染水平,进一步明确了炼油工业BTEXs污染特性、人体主要暴露途径,并进一步评估其健康风险. 结果表明,炼油区大气和土壤样品中8种BTEX的平均浓度分别为49.2 μg·m−3和578.3 g·g−1,其中冶炼区和产品储存区BTEXs浓度水平明显高于原油储存区、办公区和周边居民区. 呼吸吸入BTEXs暴露量比口服摄入高约一个数量级,表明BTEXs主要暴露途径为呼吸暴露. 非致癌风险结果表明,炼油工业区BTEXs的非致癌风险值均小于安全水平(HI<1),说明不存在非致癌风险. 另外,致癌风险评估结果表明,乙苯无明显致癌风险,可以忽略不计. 苯的致癌风险均超过10−4,表明具有较高的致癌风险,需要引起一定的关注.

-

关键词:

- 苯系物(BTEXs) /

- 炼油工业 /

- 环境介质 /

- 健康风险

Abstract: In this study, atmospheric and soil samples were collected and detected during Year 2021—2022. Environmental distribution of benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, m, p-xylene, styrene, o-xylene, and cumene (BTEXs) in petroleum refinery area of China were systematically investigated by measuring their concentrations in environmental matrices. This study identified the main ways of exposure to BTEXs and assessed the human health risks. The average concentrations of eight BTEXs were 49.2 μg·m−3 in air and 578.3 µg·g−1 in soil samples. At the smelting and the product storage subarea, the BTEXs concentrations were significantly higher than the office subarea crude oil storagearea and surrounding areas. The BTEXs via air inhalation exposure was one order of magnitude higher than that the soil ingestion exposure, indicating that the primary exposure pathway for BTEXs was inhalation exposure. HI of both inhalation and soil ingestion was lower than the safe level (HI<1), indicating the no non-carcinogenic risk in this studied area. In addition, Ethylbenzene had no significant carcinogenic risk, which could be ignored. The carcinogenic risk of benzene via inhalation exceeded the acceptable level (10−4) in petroleum refinery area, which needed to be paid attention.-

Key words:

- benzene series (BTEXs) /

- petroleum refinery /

- environmental matrices /

- health risk

-

-

表 1 化合物的SIM参数

Table 1. MS parameters of compounds

化合物

Compounds定性离子

Quantization ion(m/z)定量离子

Characterized ions(m/z)苯(Benzene) 78 77, 50 甲苯(Toluene) 92 91 乙苯(Ethylbenzene) 91 106 间+对二甲苯(p,m-Xylene) 91 106 邻二甲苯(O-xylene) 104 78, 103 苯乙烯(Styrene) 106 91 异丙苯(Cumene) 105 120 氟苯(Fluorobenzene) 96 — 表 2 参考综合风险信息系统中(IRIS)[30]的单位吸入非致癌风险浓度(Rfc)、参考口服摄入剂量(RfD);单位吸入致癌风险浓度(IUR)和经口摄入致癌因子(SF)

Table 2. Refer to Integrated Risk Information System(IRIS) of Inhalation reference concentration (Rfc), the reference oral intake dose (RfD); Inhalation Unit of carcinogenic risk (IUR) and the oral intake carcinogenic intensity factor (SF)

化合物

Compounds单位吸入非致癌风险浓度

Rfc/( mg·m−3)经口摄入参考剂量

RfD/(mg·kg−1d−1)单位吸入致癌风险浓度

IUR/(mg·m−3)−1经口摄入致癌因子

SF/(mg·kg−1d−1)苯(Benzene) 3.0×10−2 4.0×10−3 7.8×10−3 5.5×10−2 甲苯(Toluene) 5.0 8.0×10−2 — — 乙苯(Ethylbenzene) 1.0 1.0×10−1 2.5×10−3 1.1×10−2 对+间二甲苯(p,m-Xylene) 1.0×10−1 2.0×10−1 — — 苯乙烯(Styrene) 1.0 1.0×10−1 — — 邻二甲苯(O-xylene) 1.0×10−1 2.0×10−1 — — 异丙苯(Cumene) — — — — 表 3 吸入和口服摄入BTEXs危险商(HQs)和危害指数(HIs)

Table 3. the hazard quotient (HQs) and hazard index (HIs)of BTEXs analogs via inhalation and soil ingestion

功能分区 HQs (Inhalation) HIs 苯

Benzene甲苯

Toluene乙苯

Ethylbenzene对+间二甲苯

p,m-Xylene苯乙烯

Styrene邻二甲苯

O-xylene办公区 1.46×10−3 2.2×10−7 9.90×10−7 1.88×10−5 3.57×10−7 6.35×10−6 1.48×10−3 原油储存区 9.49×10−4 2.40×10−7 9.40×10−7 2.62×10−5 5.59×10−7 5.16×10−6 9.82×10−4 产品储存区 2.36×10−3 3.16×10−7 9.04×10−6 4.48×10−5 6.17×10−7 6.24×10−6 2.42×10−3 冶炼区 4.87×10−3 2.59×10−7 3.66×10−6 2.99×10−5 5.11×10−7 5.92×10−6 4.96×10−3 居民区 1.35×10−3 9.22×10−8 4.38×10−6 2.26×10−5 7.58×10−7 8.35×10−6 1.39×10−3 对照区 9.21×10−4 7.42×10−8 1.64×10−6 9.82×10−6 2.58×10−7 2.50×10−6 9.35×10−4 办公区 5.57×10−7 4.25×10−10 0 0 0 9.06×10−9 5.67×10−7 原油储存区 1.34×10−4 4.24×10−9 5.03×10−8 1.10×10−8 1.10×10−9 2.58×10−7 1.35×10−4 产品储存区 4.30×10−4 1.12×10−7 6.85×10−7 1.79×10−8 1.79×10−9 1.11×10−6 4.32×10−4 冶炼区 1.62×10−4 3.36×10−8 2.10×10−8 1.09×10−8 1.09×10−9 3.96×10−7 1.62×10−4 居民区 1.81×10−5 5.10×10−9 1.34×10−8 1.35×10−8 1.35×10−9 1.48×10−8 1.81×10−5 对照区 3.69×10−6 1.45×10−9 1.00×10−9 8.89×10−9 8.89×10−10 1.03×10−8 3.71×10−6 表 4 苯和乙苯致癌风险

Table 4. Carcinogenic risk of Benzene and Ethylbenzene

功能分区 Riskinh Risking 苯(Benzene) 乙苯(Ethylbenzene) 苯(Benzene) 乙苯(Ethylbenzene) 办公区 3.41×10−4 2.47×10−6 2.66×10−6 6.19×10−9 原油储存区 2.22×10−4 2.35×10−6 3.15×10−5 1.26×10−7 产品储存区 5.52×10−4 2.26×10−5 1.01×10−4 1.71×10−6 冶炼区 1.14×10−3 1.76×10−5 4.71×10−5 5.56×10−7 居民区 3.16×10−4 1.10×10−5 4.23×10−6 3.35×10−8 对照区 2.15×10−4 4.11×10−6 8.64×10−7 2.50×10−9 -

[1] 全国土壤污染状况调查公报 [J]. 国土资源通讯, 2014, (8): 26-29. Report on the national general survey of soil contamination[J]. National Land & Resources Information 2014, (8): 4 (in Chinese).

[2] 薛学通. 开启向石油和化学工业强国跨越的新征程[J]. 中国石化, 2018(12): 17-21. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-457X.2018.12.004 XUE X T. Start a new journey to become a powerful country in petroleum and chemical industry[J]. China Petroleum and Chemical Industry, 2018(12): 17-21 (in Chinese). doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-457X.2018.12.004

[3] BALTRĖNAS P, BALTRĖNAITĖ E, ŠEREVIČIENĖ V, et al. Atmospheric BTEX concentrations in the vicinity of the crude oil refinery of the Baltic region[J]. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 2011, 182(1): 115-127. [4] YEN C H, HORNG J J. Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emission characteristics and control strategies for a petrochemical industrial area in middle Taiwan[J]. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A, 2009, 44(13): 1424-1429. doi: 10.1080/10934520903217393 [5] FENG Y X, XIAO A S, JIA R Z, et al. Emission characteristics and associated assessment of volatile organic compounds from process units in a refinery[J]. Environmental Pollution (Barking, Essex: 1987), 2020, 265(Pt B): 115026. [6] RAS M R, MARCÉ R M, BORRULL F. Characterization of ozone precursor volatile organic compounds in urban atmospheres and around the petrochemical industry in the Tarragona region[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2009, 407(14): 4312-4319. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.04.001 [7] YOUSEFIAN F, HASSANVAND M S, NODEHI R N, et al. The concentration of BTEX compounds and health risk assessment in municipal solid waste facilities and urban areas[J]. Environmental Research, 2020, 191: 110068. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110068 [8] VERNER J, SEJKOROVÁ M, VESELÍK P. Volatile organic compounds in motor vehicle interiors under various conditions and their effect on human health[J]. Scientific Journal of Silesian University of Technology Series Transport, 2020, 107: 205-216. doi: 10.20858/sjsutst.2020.107.16 [9] XIONG Y, BARI M A, XING Z Y, et al. Ambient volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in two coastal cities in western Canada: Spatiotemporal variation, source apportionment, and health risk assessment[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 706: 135970. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135970 [10] JI Y Y, GAO F H, WU Z H, et al. A review of atmospheric benzene homologues in China: Characterization, health risk assessment, source identification and countermeasures[J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2020, 95: 225-239. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2020.03.035 [11] SAZAKLI E, LEOTSINIDIS M. Odor nuisance and health risk assessment of VOC emissions from a rendering plant[J]. Air Quality Atmosphere & Health, 2021, 14(3): 301-312. [12] LYU X P, CHEN N, GUO H, et al. Ambient volatile organic compounds and their effect on ozone production in Wuhan, central China[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2016, 541: 200-209. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.09.093 [13] BARI M A, KINDZIERSKI W B. Ambient volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in communities of the Athabasca oil sands region: Sources and screening health risk assessment[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2018, 235: 602-614. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.12.065 [14] ROVIRA J, NADAL M, SCHUHMACHER M, et al. Environmental impact and human health risks of air pollutants near a large chemical/petrochemical complex: Case study in Tarragona, Spain[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 787: 147550. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147550 [15] ZHENG H, KONG S F, YAN Y Y, et al. Compositions, sources and health risks of ambient volatile organic compounds (VOCs) at a petrochemical industrial park along the Yangtze River[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 703: 135505. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135505 [16] LI L, ZHANG D, HU W, et al. Improving VOC control strategies in industrial parks based on emission behavior, environmental effects, and health risks: A case study through atmospheric measurement and emission inventory[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2023, 865: 161235. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.161235 [17] RAJABI H, HADI MOSLEH M, MANDAL P, et al. Emissions of volatile organic compounds from crude oil processing - Global emission inventory and environmental release[J]. The Science of the Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 727: 138654. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138654 [18] 刘营营, 王丽涛, 齐孟姚, 等. 邯郸大气VOCs污染特征及其在O3生成中的作用[J]. 环境化学, 2020, 39(11): 3101-3110. doi: 10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2019112301 LIU Y Y, WANG L T, QI M Y, et al. Characteristics of atmospheric VOCs and their role in O3 generation in Handan[J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2020, 39(11): 3101-3110 (in Chinese). doi: 10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2019112301

[19] 张超, 林伟立, 韩婷婷, 等. 北京城区大气苯系物变化特征及其环境意义[J]. 环境化学, 2022, 41(2): 460-469. doi: 10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2020092203 ZHANG C, LIN W L, HAN T T, et al. Exploring the variations in ambient BTEX at urban Beijing and its environmental implications[J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2022, 41(2): 460-469 (in Chinese). doi: 10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2020092203

[20] LIN M Y, HOROWITZ L W, COOPER O R, et al. Revisiting the evidence of increasing springtime ozone mixing ratios in the free troposphere over western North America[J]. Geophysical Research Letters, 2015, 42(20): 8719-8728. doi: 10.1002/2015GL065311 [21] GUENGERICH F P, KIM D H, IWASAKI M. Role of human cytochrome P-450 IIE1 in the oxidation of many low molecular weight cancer suspects[J]. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 1991, 4(2): 168-179. doi: 10.1021/tx00020a008 [22] RUMCHEV K B, SPICKETT J T, BULSARA M K, et al. Domestic exposure to formaldehyde significantly increases the risk of asthma in young children[J]. The European Respiratory Journal, 2002, 20(2): 403-408. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00245002 [23] ZHU J, YAN L I, YONG L, et al. Determination of Metabolites of Benzene Compounds and Trichloroethylene in Urinary by Isotope Dilution-Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry[J]. Chinese Journal of Analytical Chemistry, 2016, 44(01): 81-87. [24] 程水源, 李文忠, 魏巍, 等. 炼油厂分季节VOCs组成及其臭氧生成潜势分析[J]. 北京工业大学学报, 2013, 39(3): 438-444,465. doi: 10.11936/bjutxb2013030438 CHENG S Y, LI W Z, WEI W, et al. Refinery VOCs seasonal composition and analysis of ozone formation potential[J]. Journal of Beijing University of Technology, 2013, 39(3): 438-444,465. (in Chinese) doi: 10.11936/bjutxb2013030438

[25] CHEN J, SUN L, JIA H J, et al. Effects of seasonal variation on spatial and temporal distributions of ozone in northeast China[J]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2022, 19(23): 15862. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192315862 [26] WEI W, CHENG S Y, LI G H, et al. Characteristics of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted from a petroleum refinery in Beijing, China[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2014, 89: 358-366. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.01.038 [27] LIU K K, ZHANG C L, CHENG Y, et al. Serious BTEX pollution in rural area of the North China Plain during winter season[J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2015, 30(4): 186-190. [28] CHEN R N, LI T Z, HUANG C T, et al. Characteristics and health risks of benzene series and halocarbons near a typical chemical industrial park[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 289: 117893. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117893 [29] 中华人民共和国环境保护部. 土壤和沉积物 挥发性有机物的测定 顶空/气相色谱法: HJ 741—2015[S]. 北京: 中国环境科学出版社, 2015. Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People's Republic of China. Soil and sediment—Determination of volatile organic compounds—Headspace gas chromatography: HJ 741—2015[S]. Beijing China Environmental Science Press, 2015(in Chinese).

[30] US EPA. Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund (RAGS), Volume I: Human Health Evaluation Manual (Part F, Supplemental Guidance for Inhalation Risk Assessment) [J]. 2009. [31] DUMANOGLU Y, KARA M, ALTIOK H, et al. Spatial and seasonal variation and source apportionment of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in a heavily industrialized region[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2014, 98: 168-178. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.08.048 [32] YANG S, YAN X L, ZHONG L R, et al. Benzene homologues contaminants in a former herbicide factory site: Distribution, attenuation, risk, and remediation implication[J]. Environmental Geochemistry and Health, 2020, 42(1): 241-253. doi: 10.1007/s10653-019-00342-2 [33] 谭冰, 王铁宇, 李奇锋, 等. 农药企业场地土壤中苯系物污染风险及管理对策[J]. 环境科学, 2014, 35(6): 2272-2280. TAN B, WANG T Y, LI Q F, et al. Risk assessment and countermeasures of BTEX contamination in soils of typical pesticide Factory[J]. Environmental Science, 2014, 35(6): 2272-2280 (in Chinese).

[34] LEI R R, SUN Y M, ZHU S, et al. Investigation on distribution and risk assessment of volatile organic compounds in surface water, sediment, and soil in a chemical industrial park and adjacent area[J]. Molecules, 2021, 26(19): 5988. doi: 10.3390/molecules26195988 [35] LIU B H, CHEN L, HUANG L X, et al. Distribution of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in surface water, soil, and groundwater within a chemical industry park in Eastern China[J]. Water Science and Technology:a Journal of the International Association on Water Pollution Research, 2015, 71(2): 259-267. doi: 10.2166/wst.2014.499 [36] 童玲, 郑西来, 李梅, 等. 不同下垫面苯系物的挥发行为研究[J]. 环境科学, 2008, 29(7): 2058-2062. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:0250-3301.2008.07.050 TONG L, ZHENG X L, LI M, et al. Volatilization behavior of BTEX on different underlying materials[J]. Environmental Science, 2008, 29(7): 2058-2062 (in Chinese). doi: 10.3321/j.issn:0250-3301.2008.07.050

-

下载:

下载: