-

砷(As)被世界卫生组织(WHO)列为一类人类致癌物[1],根据2014年我国发布的《全国土壤污染调查公报》,我国土壤中As的超标率为2.7%,是土壤中主要的超标污染物之一[2]. 在稻田淹水状况下,土壤处于厌氧状态,土壤中的As容易被还原溶解释放到溶液中,且从As(Ⅴ)转化为毒性更强的As(Ⅲ)[3-4]. 稻田中的As被水稻吸收后[5-6],增加了居民通过食用大米而暴露于As污染的风险[7],因此稻田的As污染问题一直受到人们的关注.

农田土壤中化肥的施用增加了铵态氮,这些铵态氮经硝化作用后可以转化为

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ ,造成农田中$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的积累[8]. 据报道[9-11],京郊农田土中硝态氮浓度范围为1.05—1.80 mg∙kg−1,黑河地区老绿洲农田中硝态氮浓度范围为4.82—16.31 mg∙kg−1,安国市农田土壤表层土中硝态氮浓度范围为13.71—184.65 mg∙kg−1.通常认为厌氧状态下As的溶出和铁氧化物还原溶解相关[4, 12-13],尽管

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的氧化还原电位高于Fe(Ⅲ)[14],但实际土壤中由于铁氧化物浓度与$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 浓度差距较大,同时氧化还原过程还与沉淀过程耦合,因此,$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 对土壤中As溶出的影响效应和机制尚未完全清楚. 尽管国内外学者针对$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 对土壤Fe还原和As溶出的影响机制取得了很多重要成果,如部分研究观察到$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的加入对As和Fe溶出的抑制作用[15-18],部分实验关注于微生物或Fe(Ⅱ)的作用,采用单一菌种构建淹水体系[19-21]或加入外源Fe(Ⅱ)[22]. 但实际淹水过程中$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 对土壤中As的溶出与还原的影响及机制仍待进一步探究,例如$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 对As在固相上的价态的影响,$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 对As可能存在的氧化作用,$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 消耗程度和铁氧化物还原溶解的关联等.为探明淹水状态下

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 对不同土壤中As的溶出与还原的影响及机制,本实验详细测定了淹水条件下土壤氧化还原电位(Eh)、给电子能力(EDC)、pH、Fe和As的还原溶出、固相Fe的组分与价态,以及土壤固相各组分上的As(Ⅲ)和As(Ⅴ),以阐明$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 对土壤中As溶出效应和机制的影响. -

实验采用的3种As污染土壤分别取自贵州省黔南州都匀市固坝镇固坝村(DY)、浙江省杭州市淳安县梓桐镇三联村(CA)、贵州省黔南州罗甸县董架乡东跃村(LD). 土壤样品采回后,去除石块等杂质,在室温下自然风干,研磨过20目筛后储存备用. 土壤基本性质如表1所示.

-

称取10.00 g过筛土壤,置于50 mL的厌氧瓶中,分别加入20 mL含有0.1 mmol∙L−1葡萄糖的不同浓度的NaNO3溶液,加入的NaNO3浓度分别为100 、10 、0 mmol∙L−1,分别为高浓度

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组(HN),低浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组(LN),空白对照组(ck). 然后用氮气吹扫厌氧瓶顶空15 min,压盖后置于恒温振荡箱中培养,温度设置为25 ℃,转速设置为200 r·min−1. 分别在第10、20、30、40、60、80、100 天进行破坏性取样,在厌氧手套箱中测定悬浮液的氧化还原电位(Eh)、给电子能力(EDC)、pH;在厌氧手套箱中将悬浮液离心过膜,对上清液加入10 μL的2 mol∙L−1的盐酸溶液,以防止Fe和As发生氧化,放入4 ℃冰箱中保存待测,将固相放入−80 ℃冰箱中保存待测. 实验所用纯水均为超纯水,且已煮沸除氧. 每个处理设置3个平行.给电子能力(EDC)的测定使用铁氰化钾法,此法可以用于定量衡量土壤的还原给电子能力[23]. 即取悬浮液0.5 mL,加入5 mL的含2 mmol∙L−1铁氰化钾和3 mol∙L−1氯化钠的溶液,在手套箱中以100 r·min−1振荡24 h后,离心过膜,使用酶标仪(ELx800,美国Biotek)以水为空白测定上清液在420 nm处的吸光度.

总铁(TFe)和Fe(Ⅱ)浓度的测定采用邻菲罗啉比色法,测定TFe时,在加入邻菲罗啉前先用盐酸羟胺还原样品,使用酶标仪(ELx800,美国Biotek)以水为空白测定510 nm处的吸光度,Fe(Ⅲ)浓度为TFe和Fe(Ⅱ)浓度的差值. 使用原子荧光光谱仪(AFS-8520,北京海光仪器有限公司)分别测定总砷(TAs)和As(Ⅲ)的浓度,As(Ⅴ)浓度为TAs和As(Ⅲ)浓度的差值. 使用离子色谱仪(ICS-5000,美国赛默飞世尔)测定液相中

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的浓度.固相中Fe的形态采用Lueder总结的连续提取法测定[24],固相中As的形态采用Lock连续提取方法[25]测定,该方法是对Wenzel连续提取法[26]的改进,在提取过程中不改变As的价态,具体步骤如表2所示.

-

整个取样时间内

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的消耗如图1所示,和许多研究一致的是,$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的消耗主要集中在淹水的前期[15, 19, 27]. 对于加入高浓度NaNO3溶液的各个实验组,其$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的消耗表现出相似的模式,即$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的消耗在前20天或前10天已基本完成,之后溶液中$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的浓度一直在较高水平波动,实验过程中,DY、LD、CA土中$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 浓度最低分别为50.7、38.3、32.8 mmol∙L−1,对应的消耗量百分比分别为49.3%、61.7%、67.2%. 对于低浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的处理组,$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 在一开始消耗速度最快,LD土在第10天就已经消耗完全,CA土在第20天仅剩余0.71 mmol∙L−1,但直到第60天才消耗完全,而DY土在第20天浓度为4.81 mmol∙L−1,在第100天浓度为3.39 mmol∙L−1,前20天消耗了51.9%的$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ ,后80天只消耗了14.1%. 土壤中$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的消耗速率与微生物的活动密切相关[15, 28],推测3种土壤中的硝酸盐还原菌群活性有以下顺序:LD > CA > DY. -

取样时间内土壤悬浮液的氧化还原电位(Eh)如图2(a—c)所示. 空白对照组的Eh下降较快,在第10天,DY、CA、LD的3种土的Eh就已分别下降到83.2、25.95、−154.4 mV,之后缓慢下降,在第100天分别降至−13.95、−58.3、−182.6 mV.

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的加入显著抑制了土壤悬浮液Eh的下降过程,且抑制效应和加入的$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 浓度显著相关,高浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组的Eh始终高于低浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组. 唯一的例外是LD土的低浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组,该处理组的$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 在第10天已被完全消耗,因此未观察到$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 对Eh下降过程的抑制作用. 不同的Eh指示着不同的还原过程,按照土壤中各体系氧化还原电位的顺序,Eh由高到低依次发生的是反硝化、Mn(Ⅳ)还原、Fe(Ⅲ)还原、$ \text{S}{\text{O}}_{\text{4}}^{{2-}} $ 还原、甲烷生成[14],其中淹水条件下Mn(Ⅳ)还原和Fe(Ⅲ)还原通常同时发生[29-30].取样时间内土壤悬浮液的给电子能力(EDC)如图2(d—f)所示. 空白对照组的EDC值较高,且随时间呈上升趋势,而NaNO3的加入抑制了EDC值. 对于DY土,高浓度或低浓度

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组的$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 在100天内始终处于较高水平,所以两种处理的EDC值接近,均处于较低水平. 对于CA土,低浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理和高浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理在第10天和第20天的EDC值相近,而在第30天后,随着低浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组中的大部分$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 被消耗,其EDC值也随之上升,明显高于高浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组. 对于LD土,低浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组的$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 在第10天就被完全消耗,所以其EDC值和空白对照组接近,而高浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组的$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 始终处于较高水平,所以EDC值大幅低于空白对照组. 实验得到的EDC值和Eh值具有较好的相关性(R= −0.946,P< 0.01),说明EDC值也能在一定程度上指示发生的还原过程.取样时间内土壤悬浮液的pH如图2(g—i)所示. 在未加入

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的情况下,DY土悬浮液呈酸性(5.45—5.77),CA土悬浮液呈中性(6.43—6.62),LD土悬浮液呈碱性(7.56—8.08). 对于各组土壤悬浮液,加入低浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 后,pH有所上升,而加入高浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 后,pH有所下降,CA土尤其明显. 加入低浓度NaNO3后,由于$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的还原过程会消耗H+[19, 31],如化学方程式(1)所示,所以体系的pH值上升. 而加入高浓度NaNO3后,由于大量的Na+与土壤黏土矿物表面的H+发生阳离子交换[32],所以体系的pH值略有下降. -

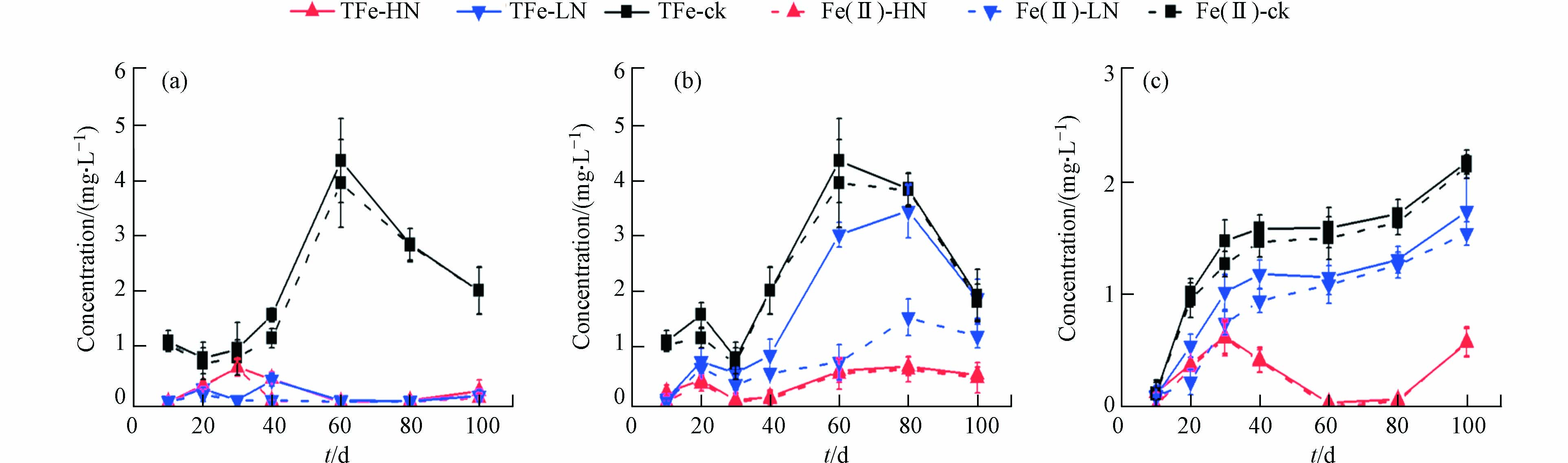

不同取样时间内各土壤中Fe溶出浓度和价态变化如图3所示. 对于不同的土壤,高浓度

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的加入都强烈地抑制了Fe的溶出,这与前人的研究结果一致[17-20, 22]. 一般认为,厌氧状态下铁氧化物上的Fe(Ⅲ)在微生物作用下被还原为Fe(Ⅱ),之后释放到溶液中[33-35]. 而$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的加入导致$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 被优先还原,从而抑制了铁氧化物的还原溶解. 但低浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组中不同的土壤表现出不同的溶出模式.DY土中由于低浓度

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组的$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 始终未消耗完全,所以表现出与高浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组一样的效应,即Fe的溶出被强烈抑制.CA土低浓度

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组的前40天中,$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 并未完全消耗完,因此溶出的Fe浓度较低,而在第60天左右$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 消耗完全后,溶出的总铁(TFe)浓度才开始升高. 有趣的是,尽管第60、80、100 天监测到较高的TFe浓度,但其中Fe(Ⅱ)的比例却不高,Fe(Ⅱ)/TFe分别为23.6%,44.4%,63.7%,远低于空白组. 这期间我们同时监测到溶液中有下降趋势的$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}^{-} $ 浓度,分别为(0.26±0.05)、(0.10±0.01)、(0.07±0.01)mmol·L−1. Schaedler等[36]的研究表明,$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}^{-} $ 能够将溶液中的Fe(Ⅱ)氧化为Fe(Ⅲ),因此溶液中残留的$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的还原产物$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}^{-} $ 等可能是造成60 d及随后取样中较低的Fe(Ⅱ)/TFe值的原因. 这期间较高的Eh值(66.8—92.3 mV)也佐证了这一点,因为土壤中Fe(Ⅲ)的大量还原通常发生在50 mV以下[37],较高的Eh指示着其它还原过程的伴随发生.LD土对

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的消耗最快,第10天左右时消耗完全,因而铁氧化物的还原溶解从第10天已经开始,溶出的Fe随之上升,且溶出的Fe几乎全为Fe(Ⅱ),和空白对照组中Fe的溶出表现出相同的模式. 同时,低浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组和空白对照组溶出的Fe始终相差约(0.44±0.02)mg∙L−1,造成这种差距的原因可以从两方面进行解释:一方面,如图2所示,低浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组和空白对照组的Eh相近,但pH始终比空白对照组高0.15左右,造成了低浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组和空白对照组溶出Fe之间稳定的差值[38-39],反映出Fe的溶出受Eh和pH的双重控制效应;另一方面,$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的加入使体系消耗了更多电子,影响了后续的Fe还原过程. 还需要指出的是,除了上文提到的CA的低浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组,其余各组的溶出Fe几乎全为Fe(Ⅱ).不同取样时间内As的溶出浓度和价态如图4所示. 对于空白对照组,可以看出,As的溶出需要一定的时间,DY土在第60天后开始大量溶出,CA土在第40天后开始大量溶出,LD土在第20天后开始大量溶出,与各土的还原能力一致. 总体来看As与Fe的溶出在时间上有很好的匹配度,同时As和Fe的溶出浓度也具有较好的相关性(R= 0.775,P< 0.01),说明土壤中As的溶出主要由铁氧化物控制,铁氧化物的还原溶解导致吸附其上的As的溶出[4, 12-13]. 溶出的As(Ⅴ)会通过呼吸性还原或解毒性还原两种方式被微生物还原为As(Ⅲ)[40],其中前者由异养型As呼吸还原微生物(DARPs)驱动,它们使用As(Ⅴ)作为电子受体,以各种有机或无机化合物作为电子给体,通过呼吸作用将As(Ⅴ)还原为As(Ⅲ),是As还原的主要途径[41-43]. As开始大量溶出后,溶液中的As(Ⅲ)/TAs也基本稳定,LD、CA、DY的3种土的As(Ⅲ)/TAs范围分别为56.3%—68.7%,65.1%—75.8%,71.0%—86.5%. 推测As(Ⅲ)/TAs的比例和土壤悬浮液的pH有关,据Niazi等报道[44],pH=9时As的还原程度最小,pH=6时As的还原程度最大,本研究中随着3种土壤溶液pH从8下降到6,As(Ⅲ)/TAs比例也明显上升.

对于高浓度

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组,可以看出由于$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 浓度较高,都强烈地抑制了As的还原溶出,与前人的研究结果一致[17, 19].对于低浓度

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组,不同的土壤表现出不同的溶出模式. 其中DY土的$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 在整个取样时间内都未被完全消耗,因此As的溶出被强烈抑制. 而LD土的$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 在第10天就已经消耗完全,所以As(Ⅲ)和As(Ⅴ)的浓度与空白对照组相近. 但是CA土中As溶出和Fe溶出并不完全一致,在40 d$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 消耗完后,Fe开始大量溶出,但As的溶出量却很小,且溶出As大部分为As(Ⅴ). 考虑到此时溶液中仍残留较多的$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}^{-} $ ,说明$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的还原产物对As的还原溶解也具有很强的抑制作用. 以往的研究从As污染土壤中分离出了一些厌氧As氧化菌,这些微生物能够以$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 为电子受体,将As(Ⅲ)氧化为As(Ⅴ) [16, 20, 45-46]. Zhang等[45]在水稻土中分离得到了一类自养型厌氧As氧化菌,在加入$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的淹水体系中,该菌株的存在导致孔隙水总As中As(Ⅲ)的占比从76%下降到22%,并导致固相磷酸可提取态总As中As(Ⅲ)的占比从94%下降到11%,说明厌氧As氧化菌能够同时氧化液相和固相的As. Chen等[18]测定了淹水前后的As氧化基因aioA和As呼吸还原基因arrA的拷贝数,发现$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的施用增加了aioA的拷贝数而降低了arrA的拷贝数,说明$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 刺激了厌氧As氧化菌的活性. Zhu等[19]使用As污染土壤和单一菌种Shewanella sp. GL90构建了含有乳酸钠和$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}^{-} $ 的土壤淹水体系,观察到$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}^{-} $ 对As(Ⅲ)溶出还原的抑制作用. 可以看出,$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 及其还原产物$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}^{-} $ 的存在为厌氧As氧化菌提供了电子受体,抑制了As的还原溶出,且当溶液中仍有$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}^{-} $ 存在时,溶出的As以As(Ⅴ)为主.综上可以看出,尽管以往的实验已经观察到

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 对铁氧化物还原溶解的抑制作用[15, 21],本实验的结果进一步说明了在实际土壤中,N、Fe、As的氧化还原顺序大致为:$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 最先被还原,即使溶液中$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 浓度较低,也会阻止铁氧化物的溶解,当$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 消耗完全时,铁氧化物的还原溶出才会开始,而此时溶液中$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的残留还原产物$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}^{-} $ 等虽不能抑制铁氧化物的溶解,却能够将溶液中的Fe(Ⅱ)氧化为Fe(Ⅲ),同时$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}^{-} $ 可以抑制As的还原溶出. 分别计算溶液中TAs和TFe、Eh、EDC的相关性,结果分别为R= 0.588(P< 0.01)、R= −0.802(P< 0.01)、R= 0.837(P< 0.01),结合其它实验结果,说明EDC可能是指示土壤中As溶出能力的更好指标. -

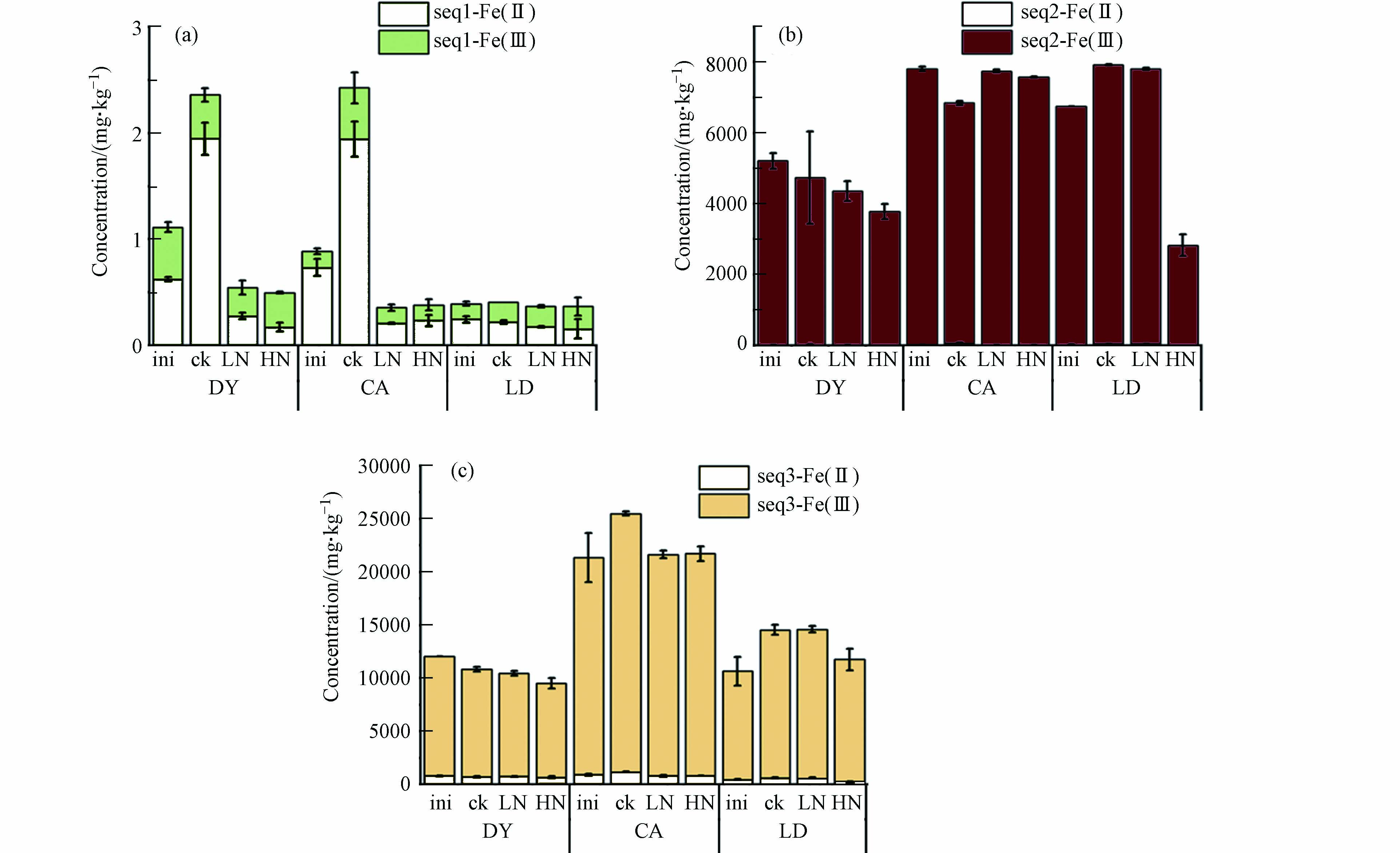

反应结束后各组Fe在固相上的形态分布与初始条件下空白对照组的比较如图5所示. 固相上晶形Fe含量最高,无定形Fe次之,而吸附态Fe含量很低. 图6展示了固相各组分Fe的Fe(Ⅱ)/TFe值,晶形Fe和无定形Fe中Fe(Ⅱ)占比极低,而吸附态Fe则以Fe(Ⅱ)为主.

根据图5,对于DY土,实验结束时,空白对照组的吸附态Fe含量升高,无定形Fe和晶形Fe含量降低,但无定形Fe中的Fe(Ⅱ)含量从19.2 mg∙kg−1上升至26.3 mg∙kg−1,

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的加入降低了吸附态Fe的含量,促进了无定形Fe和晶形Fe含量的降低,且这种促进效应和加入的$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的浓度相关. 对于CA土,实验结束时,空白对照组的吸附态Fe和晶形Fe含量升高,而无定形Fe含量降低,但无定形Fe中的Fe(Ⅱ)含量从42.4 mg∙kg−1上升至73.5 mg∙kg−1,$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的加入降低了吸附态Fe的含量,抑制了无定形Fe和晶形Fe的转化. 对于LD土,实验结束时,空白对照组的吸附态Fe略有上升,而无定形Fe和晶形Fe的含量明显上升,低浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的加入未明显影响各组分中Fe的含量,高浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的加入降低了无定形Fe和晶形Fe的含量.整体来看,淹水促进了空白对照组中各组分Fe(Ⅲ)向Fe(Ⅱ)转化(图6),而

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的加入抑制了该转化过程,从而减少了Fe(Ⅱ)的溶出. 需要注意的是,虽然LD土的低浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 实验组中的$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 在第10天就已消耗完全,第100 天各组分的Fe(Ⅱ)/TFe值仍然略有下降,说明$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的还原产物也能抑制固相上Fe(Ⅲ)向Fe(Ⅱ)转化.Lin等[15]提取了淹水前后固相Fe的形态,结果表明

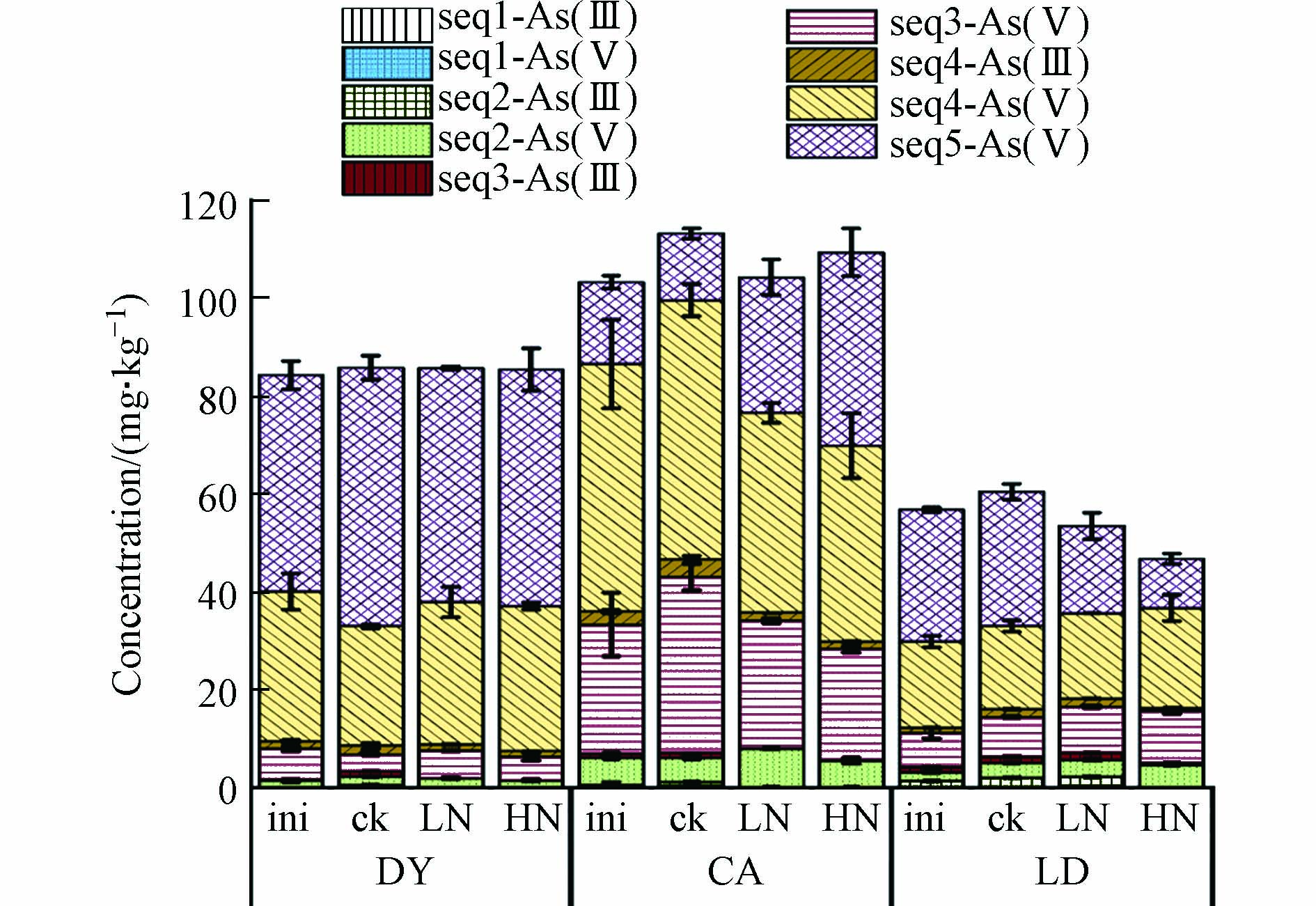

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 显著促进了晶形Fe含量的上升,对无定形Fe影响较弱,而本实验的结果表明$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 整体上降低了固相Fe各形态的含量,不同的实验结果可能是因为Lin等的实验提取晶形Fe采用的是连二亚硫酸钠—柠檬酸钠—碳酸氢钠(DCB)提取法,提取无定形Fe则是采用的草酸—草酸铵缓冲液(AAO)提取法. 对于固相Fe的价态,整体来看,还原条件下固相上各组分的Fe(Ⅲ)会向Fe(Ⅱ)转化,$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的加入会抑制该转化过程.本实验同时测定了反应结束后As在固相上的形态分布(图7). 除了残渣态As,固相上的As主要分布在无定形Fe和晶形Fe上,而易交换态的As几乎为0,佐证了As的溶出主要受铁氧化物的控制[4, 12-13]. 对于DY土,

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的加入增加了与晶形Fe相结合的As的含量;对于CA土,$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的加入减少了与无定形Fe和晶形Fe相结合的As的含量;对于LD土,$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的加入增加了与无定形Fe和晶形Fe相结合的As的含量. 相关研究[15, 21]观察到$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的加入减少了与无定形Fe相结合的As的含量,而增加了与晶形Fe相结合的As的含量,但这些结果都来自于各自使用的一种土壤. 本实验结果进一步表明,$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 对As在固相上的分布还与土壤种类、$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 浓度有关,不一定遵循同一种模式.据报道[25],本实验采用的连续提取法不改变固相As的价态. 图8展示了固相As提取第二、三、四步的As(Ⅲ)/TAs值,分别代表强吸附态As、无定形Fe结合态As和晶形Fe结合态As. 各组分的As都主要以As(Ⅴ)的价态存在. 加入

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 后,DY土和CA土中无定形Fe和晶形Fe相结合的As(Ⅲ)都有显著的下降. 例如,无定形Fe相结合的CA土的As(Ⅲ)的含量从空白对照组的0.94 mg∙kg−1下降到低浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组的0.21 mg∙kg−1和高浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组的0.16 mg∙kg−1,而低浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的加入并未明显影响LD土中无定形Fe和晶形Fe相结合的As(Ⅲ)含量,空白对照组中无定形Fe和晶形Fe相结合的As(Ⅲ)含量分别为1.30 mg∙kg−1、1.59 mg∙kg−1,低浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组则为1.32 mg∙kg−1、1.65 mg∙kg−1. 结合图7,可以说明$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的加入强烈地抑制了固相上As(Ⅴ)向As(Ⅲ)的转化,DY土和CA土的实验组或因未消耗完$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ ,或因$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 在很晚的取样时间才消耗完全,所以As(Ⅲ)/TAs的值大幅下降,而LD土的低浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组由于在第10天就已将$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 完全消耗,所以固相上As(Ⅲ)/TAs的值几乎与空白对照组持平. 通常认为[3],淹水条件下铁氧化物结合态As有两种还原路径,一种是As(Ⅴ)随着铁氧化物的还原溶解而溶出,在溶液中发生还原,另一种是在铁氧化物表面先被还原为As(Ⅲ),随后被释放到溶液中. 如图4和图8所示,实验结果表明,$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 可以强烈地抑制固相上As(Ⅴ)向As(Ⅲ)的转化过程,从而降低液相As的浓度.$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的这种抑制作用可能是由厌氧As氧化菌驱动的,厌氧As氧化菌以$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 为电子受体,将固相的As(Ⅲ)氧化为As(Ⅴ)[19, 45, 47],从而导致固相As(Ⅲ)/TAs值的大幅下降.综合来看,还原条件下固相上各组分的As(Ⅴ)会向As(Ⅲ)转化,

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的加入为厌氧As氧化菌提供了电子受体,促使固相As(Ⅲ)氧化为As(Ⅴ),$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 对As在固相上的分布与土壤种类、$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 浓度都有关. -

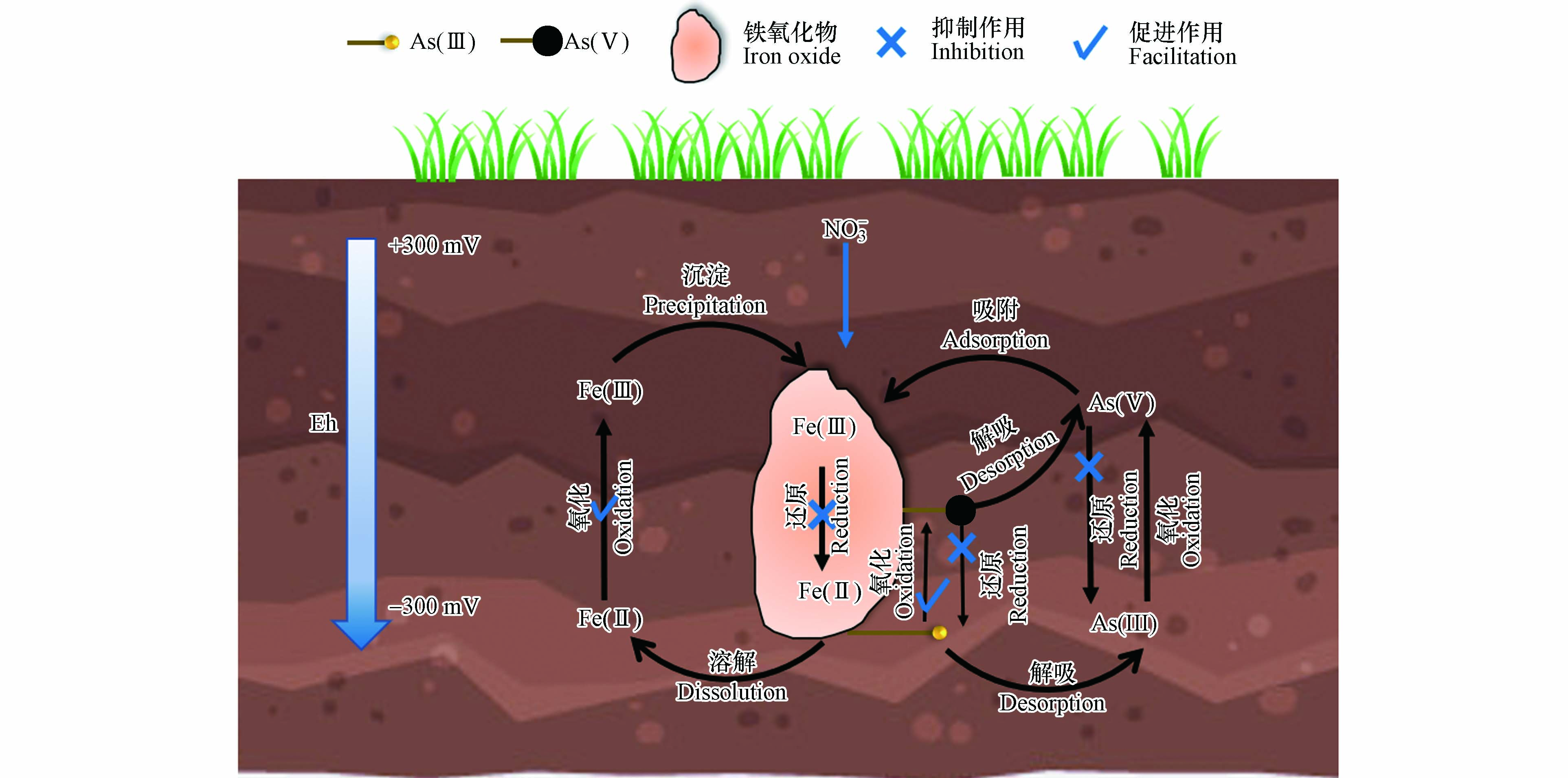

结合液相和固相提取的实验结果,我们提出了

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 影响土壤As溶出的可能机制,如图9所示. 淹水条件下,土壤中As的还原溶出和铁氧化物的还原溶解相耦合[4, 12-13],铁氧化物中的Fe(Ⅲ)被微生物还原为Fe(Ⅱ),释放进入溶液中[33-35],导致与铁氧化物相结合的As的溶出,溶出的As一部分是As(Ⅴ),这部分As会在溶液中被As还原菌还原为As(Ⅲ),还有一部分溶出As是As(Ⅲ),这部分As在固相就已被还原[3]. 加入$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 后,$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 作为电子受体会优先被还原[14],从而抑制了铁氧化物中Fe(Ⅲ)的还原,导致Fe溶出量的大幅下降,同时$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 还可以作为厌氧As氧化菌的电子受体,促使固相上As(Ⅲ)向As(Ⅴ)的转化[19, 45, 47];当$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 消耗完全后,铁氧化物才开始还原溶解,此时如果溶液中还残留$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的还原产物$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}^{-} $ 等,则可以促进溶解的Fe(Ⅱ)向Fe(III)的氧化[36],同时抑制As的溶出与还原,只有当还原产物$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}^{-} $ 等也消耗完全时,才会观察到As的大量还原溶出[19]. -

为探究厌氧条件下

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 对土壤中As的溶出与还原的影响及机制,本文测定了淹水条件下3种土壤Eh、EDC、pH、Fe和As的还原溶出、固相上Fe和As的分布及价态等指标. 结果表明,$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 显著抑制了Eh的下降,且这种抑制作用与$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 浓度有关.$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 存在时铁氧化物的还原溶解不会发生,溶液中残留的$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的还原产物$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}^{-} $ 等可能会促进液相中Fe(Ⅱ)的氧化.$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 及其还原产物可以作为厌氧As氧化菌的电子受体,促使固相上As(Ⅲ)向As(Ⅴ)的转化,抑制As的溶出及提高溶液中As(V)的比例. EDC和Eh具有良好的负相关性,二者都可以用来指示土壤悬液中氧化还原反应的进度,而EDC对As溶出的指示效果要更优于Eh.

淹水条件下硝酸根对土壤中砷溶出过程的影响与机制

Effect and mechanism of nitrate on arsenic dissolution in flooding soil

-

摘要: 本文通过对3种土壤投加低浓度(10 mmol·L−1)或高浓度(100 mmol∙L−1)的

$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ ,进行100 d的淹水实验,探究厌氧条件下$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 对土壤中As溶出的影响. 结果表明,$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 对土壤As溶出过程的影响与$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的还原过程相耦合,当$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 未消耗完全时,铁氧化物和As的还原溶出受到抑制;仅当$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 消耗完全时,铁氧化物才开始大量还原溶出. 研究还观察到某些土壤溶液中残留的$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 还原产物可能会氧化溶出的Fe(Ⅱ),导致溶液中的Fe(Ⅱ)/TFe远低于空白对照组,并同时抑制了As的溶出. 如淳安土的低浓度$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 处理组的第60、80、100天样品中Fe(Ⅱ)/TFe值分别为23.6%、44.4%、63.7%,远低于空白对照组,而此时As的溶出被推迟. 随着铁氧化物的溶出,与铁氧化物相结合的As也开始溶出,但由于之前$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 抑制了固相上As(Ⅴ)的还原,导致液相As(Ⅴ)/TAs值较高,且As(Ⅴ)因受$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 的还原产物的影响而难以被还原. 对于土壤固相,$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 降低了固相各组分的Fe(Ⅱ)或As(Ⅲ)含量,对于Fe或As固相分布的影响则与土壤种类和投加的$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ 浓度有关.Abstract: The effects of$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ on As dissolution in soil under anoxic conditions were investigated by a 100-day flooding experiment at low (10 mmol∙L−1) or high (100 mmol∙L−1) concentration of$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ in three soils. The results showed that the dissolution of As was coupled with the reduction process of$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ . When$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ was not completely consumed, it inhibited both the reduction of iron oxides and the dissolution of As. Only when$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ was completely consumed, iron oxides began to be reduced and dissolved on a massive scale. In addition, the reduction products of$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ in soil solution may also oxidize dissolved Fe(Ⅱ), resulting in a low Fe(Ⅱ)/TFe ratio in soil solution. For example, in the low$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ treatment of Chun’an soil, the Fe(Ⅱ)/TFe ratio was 23.6%, 44.4% and 63.7% on the 60th, 80th, and 100th day, respectively, much lower than those in the control group. The dissolution of As was also delayed during this period. With the dissolution of iron oxides, As bound to iron oxides began to dissolve. However, since$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ had inhibited the reduction of As(Ⅴ) in solid phase and the possible influence of the reduction products of$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ , a high As(Ⅴ)/TAs ratio in the liquid was observed. Moreover, the effects of$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ on the distribution of Fe or As in the solid phase was related to soil type and$ \text{N}{\text{O}}_{\text{3}}^{-} $ concentration. -

-

表 1 土壤基本理化性质

Table 1. Physical and chemical properties of soil

种类

SoilpH SOCa/

(mg·kg−1)DCB-Feb/

(g·kg−1)ox-Fec/

(g·kg−1)As/

(mg·kg−1)Cd/

(mg·kg−1)Cu/

(mg·kg−1)Zn/

(mg·kg−1)Pb/

(mg·kg−1)都匀DY 7.03 21.95 45.21 2.20 85.16 3.79 24.00 2498.71 367.53 淳安CA 4.69 17.56 45.05 7.67 108.47 2.91 433.98 523.25 339.99 罗甸LD 7.94 24.66 36.20 3.92 53.89 1.31 29.37 196.73 75.73 a土壤有机碳.b连二亚硫酸钠—柠檬酸钠—碳酸氢钠提取法提取的Fe.c草酸-草酸铵提取法提取的Fe.

a soil organic carbon.b Fe extracted by dithionite-citrate-bicarbonate extraction method.c Fe extracted by acid ammonium oxalate extraction method.表 2 Fe和As的连续提取法

Table 2. Sequential extraction of Fe and As

步骤

Steps组分

Fraction提取剂

Extraction agents提取条件

Extraction conditionFe 1 吸附态铁 5 mL pH=5的1 mol·L−1乙酸钠溶液 黑暗,20 ℃,100 r·min−1振荡24 h 2 弱晶形和无定形铁 5 mL 0.5 mol·L−1盐酸 黑暗,20 ℃,100 r·min−1振荡2 h 3 晶形铁 5 mL 6 mol·L−1盐酸 黑暗,20 ℃,100 r·min−1振荡24 h As 1 易交换态 12.5 mL 0.05 mol·L−1硫酸铵溶液 20 ℃,100 r·min−1振荡4 h 2 强吸附态 12.5 mL 0.05 mol·L−1磷酸二氢铵溶液 20 ℃,100 r·min−1振荡16 h 3 无定形铁结合态 25 mL 0.5 mol·L−1磷酸+ 0.1 mol·L−1盐酸羟胺 20 ℃,100 r·min−1振荡1 h 4 晶形铁结合态 12.5 mL 0.2 mol·L−1草酸铵缓冲溶液+ 0.1 mol·L−1抗坏血酸,pH=3.25 96 ℃,在光下反应0.5 h 5 残渣态 10 mL 王水 105 ℃反应2 h -

[1] WANG Z H, FU Y, WANG L L. Abiotic oxidation of arsenite in natural and engineered systems: Mechanisms and related controversies over the last two decades (1999-2020) [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2021, 414: 125488. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.125488 [2] 全国土壤污染状况调查公报[J]. 中国环保产业, 2014(5): 10-11. Bulletin on the investigation of soil pollution in China[J]. China Environmental Protection Industry, 2014(5): 10-11 (in Chinese).

[3] XU X W, CHEN C, WANG P, et al. Control of arsenic mobilization in paddy soils by manganese and iron oxides [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2017, 231: 37-47. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.07.084 [4] YAMAGUCHI N, NAKAMURA T, DONG D, et al. Arsenic release from flooded paddy soils is influenced by speciation, Eh, pH, and iron dissolution [J]. Chemosphere, 2011, 83(7): 925-932. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.02.044 [5] 曹丽霞, 李文栓, 蔺昕, 等. 叶面施硒对水稻砷吸收积累影响的研究进展[J]. 环境工程, 2023, 41(7): 271-276. CAO L X, LI W S, LIN X, et al.Effects of selenium application on arsenic uptake and accumulation in rice [J]. Environmental Engineering, 2023, 41(7): 271-276(in Chinese).

[6] 刘文菊, 赵方杰. 植物砷吸收与代谢的研究进展 [J]. 环境化学, 2011, 30(1): 56-62. LIU W J, ZHAO F J. A brief review of arsenic uptake and metabolism in plants [J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2011, 30(1): 56-62(in Chinese).

[7] 李刚, 郑茂钟, 朱永官. 福建省稻米中的砷水平及其健康风险研究 [J]. 生态毒理学报, 2013, 8(2): 148-155. doi: 10.7524/AJE.1673-5897.20130103001 LI G, ZHENG M Z, ZHU Y G. Studies on arsenic levels and its health risk of rice collected from Fujian Province [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2013, 8(2): 148-155(in Chinese). doi: 10.7524/AJE.1673-5897.20130103001

[8] LI Z L, TANG Z, SONG Z P, et al. Variations and controlling factors of soil denitrification rate [J]. Global Change Biology, 2022, 28(6): 2133-2145. doi: 10.1111/gcb.16066 [9] 杜连凤, 赵同科, 张成军, 等. 京郊地区3种典型农田系统硝酸盐污染现状调查 [J]. 中国农业科学, 2009, 42(8): 2837-2843. doi: 10.3864/j.issn.0578-1752.2009.08.024 DU L F, ZHAO T K, ZHANG C J, et al. Investigation on nitrate pollution in soils, ground water and vegetables of three typical farmlands in Beijing region [J]. Scientia Agricultura Sinica, 2009, 42(8): 2837-2843(in Chinese). doi: 10.3864/j.issn.0578-1752.2009.08.024

[10] 苏永中, 杨晓, 杨荣. 黑河中游边缘荒漠-绿洲非饱和带土壤质地对土壤氮积累与地下水氮污染的影响 [J]. 环境科学, 2014, 35(10): 3683-3691. doi: 10.13227/j.hjkx.2014.10.007 SU Y Z, YANG X, YANG R. Effect of soil texture in unsaturated zone on soil nitrate accumulation and groundwater nitrate contamination in a marginal oasis in the middle of Heihe River Basin [J]. Environmental Science, 2014, 35(10): 3683-3691(in Chinese). doi: 10.13227/j.hjkx.2014.10.007

[11] 赵姣姣, 刘文科, 刘义飞. 河北省安国市药材田与粮作田土壤硝酸盐的累积特征 [J]. 中国农业气象, 2013, 34(3): 301-305. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-6362.2013.03.008 ZHAO J J, LIU W K, LIU Y F. Characteristic of soil nitrate accumulation on herbal field and grain field in Anguo city, Hebei Province [J]. Chinese Journal of Agrometeorology, 2013, 34(3): 301-305(in Chinese). doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-6362.2013.03.008

[12] 杨明, 许丽英, 宋雨, 等. 厌氧微生物作用下土壤中砷的形态转化及其分配 [J]. 生态毒理学报, 2013, 8(2): 178-185. doi: 10.7524/AJE.1673-5897.20130228001 YANG M, XU L Y, SONG Y, et al. Speciation transformation and distribution of arsenic in soils under action of anaerobic microbial activities [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2013, 8(2): 178-185(in Chinese). doi: 10.7524/AJE.1673-5897.20130228001

[13] DENG Y X, WENG L P, LI Y T, et al. Redox-dependent effects of phosphate on arsenic speciation in paddy soils [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2020, 264: 114783. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114783 [14] KÖGEL-KNABNER I, AMELUNG W, CAO Z H, et al. Biogeochemistry of paddy soils [J]. Geoderma, 2010, 157(1/2): 1-14. [15] LIN Z J, WANG X, WU X, et al. Nitrate reduced arsenic redox transformation and transfer in flooded paddy soil-rice system [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2018, 243: 1015-1025. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.09.054 [16] ZHANG J, ZHAO S C, XU Y, et al. Nitrate stimulates anaerobic microbial arsenite oxidation in paddy soils [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2017, 51(8): 4377-4386. [17] CHEN Z L, AN L H, WEI H, et al. Nitrate alleviate dissimilatory iron reduction and arsenic mobilization by driving microbial community structure change [J]. Surfaces and Interfaces, 2021, 26: 101421. doi: 10.1016/j.surfin.2021.101421 [18] CHEN G N, DU Y H, FANG L P, et al. Distinct arsenic uptake feature in rice reveals the importance of N fertilization strategies [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2023, 854: 158801. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158801 [19] ZHU X B, ZENG X C, CHEN X M, et al. Inhibitory effect of nitrate/nitrite on the microbial reductive dissolution of arsenic and iron from soils into pore water [J]. Ecotoxicology, 2019, 28(5): 528-538. doi: 10.1007/s10646-019-02050-0 [20] WU Y F, CHAI C W, LI Y N, et al. Anaerobic As(III) oxidation coupled with nitrate reduction and attenuation of dissolved arsenic by Noviherbaspirillum species [J]. ACS Earth and Space Chemistry, 2021, 5(8): 2115-2123. doi: 10.1021/acsearthspacechem.1c00155 [21] FANG J H, XIE Z M, WANG J, et al. Bacterially mediated release and mobilization of As/Fe coupled to nitrate reduction in a sediment environment [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2021, 208: 111478. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111478 [22] WANG X Q, LIU T X, LI F B, et al. Effects of simultaneous application of ferrous iron and nitrate on arsenic accumulation in rice grown in contaminated paddy soil [J]. ACS Earth and Space Chemistry, 2018, 2(2): 103-111. doi: 10.1021/acsearthspacechem.7b00115 [23] SUN T R, GUZMAN J J L, SEWARD J D, et al. Suppressing peatland methane production by electron snorkeling through pyrogenic carbon in controlled laboratory incubations [J]. Nature Communications, 2021, 12: 4119. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24350-y [24] LUEDER U, MAISCH M, LAUFER K, et al. Influence of physical perturbation on Fe(II) supply in coastal marine sediments [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2020, 54(6): 3209-3218. [25] LOCK A, WALLSCHLÄGER D, McMURDO C, et al. Validation of an updated fractionation and indirect speciation procedure for inorganic arsenic in oxic and suboxic soils and sediments [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2016, 219: 1102-1108. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.09.013 [26] WENZEL W W, KIRCHBAUMER N, PROHASKA T, et al. Arsenic fractionation in soils using an improved sequential extraction procedure [J]. Analytica Chimica Acta, 2001, 436(2): 309-323. doi: 10.1016/S0003-2670(01)00924-2 [27] LI X M, QIAO J T, LI S A, et al. Bacterial communities and functional genes stimulated during anaerobic arsenite oxidation and nitrate reduction in a paddy soil [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2020, 54(4): 2172-2181. [28] XIAO Z X, JIANG Q T, LI Y, et al. Enhanced microbial nitrate reduction using natural manganese oxide ore as an electron donor [J]. Journal of Environmental Management, 2022, 306: 114497. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.114497 [29] MAGUFFIN S C, ABU-ALI L, TAPPERO R V, et al. Influence of manganese abundances on iron and arsenic solubility in rice paddy soils [J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2020, 276: 50-69. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2020.02.012 [30] KAPPLER A, BRYCE C, MANSOR M, et al. An evolving view on biogeochemical cycling of iron [J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2021, 19(6): 360-374. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-00502-7 [31] LIU X L, ZHANG Y, LI X H, et al. Effects of influent nitrogen loads on nitrogen and COD removal in horizontal subsurface flow constructed wetlands during different growth periods of Phragmites australis [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 635: 1360-1366. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.03.260 [32] PIVOVAROV S. Diffuse sorption modeling: Apparent H/Na, or the same, Al/Na exchange on clays [J]. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 2009, 336(2): 898-901. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2009.04.018 [33] 孙丽蓉, 王旭刚, 郭大勇, 等. 旱作褐土中铁氧化物的厌氧还原动力学特征 [J]. 土壤学报, 2013, 50(1): 106-112. doi: 10.11766/trxb201201120013 SUN L R, WANG X G, GUO D Y, et al. Dynamics of anaerobic reduction of iron oxides in upland cinnamon soils [J]. Acta Pedologica Sinica, 2013, 50(1): 106-112(in Chinese). doi: 10.11766/trxb201201120013

[34] WANG Z, LIU X W, LIANG X F, et al. Flooding-drainage regulate the availability and mobility process of Fe, Mn, Cd, and As at paddy soil [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2022, 817: 152898. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152898 [35] 钱子妍, 吴川, 何璇, 等. 铁循环微生物对环境中重金属的影响研究进展 [J]. 环境化学, 2021, 40(3): 834-850. doi: 10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2020050901 QIAN Z Y, WU C, HE X, et al. Study on the influence of iron redox cycling microorganisms on heavy metals in the environment [J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2021, 40(3): 834-850(in Chinese). doi: 10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2020050901

[36] SCHAEDLER F, KAPPLER A, SCHMIDT C. A revised iron extraction protocol for environmental samples rich in nitrite and carbonate [J]. Geomicrobiology Journal, 2018, 35(1): 23-30. doi: 10.1080/01490451.2017.1303554 [37] YU K W, BÖHME F, RINKLEBE J, et al. Major biogeochemical processes in soils-a microcosm incubation from reducing to oxidizing conditions [J]. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 2007, 71(4): 1406-1417. doi: 10.2136/sssaj2006.0155 [38] GUSTAVE W, YUAN Z F, SEKAR R, et al. Soil organic matter amount determines the behavior of iron and arsenic in paddy soil with microbial fuel cells [J]. Chemosphere, 2019, 237: 124459. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.124459 [39] JIANG W, HOU Q Y, YANG Z F, et al. Evaluation of potential effects of soil available phosphorus on soil arsenic availability and paddy rice inorganic arsenic content [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2014, 188: 159-165. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2014.02.014 [40] JIA M R, TANG N, CAO Y, et al. Efficient arsenate reduction by As-resistant bacterium Bacillus sp. strain PVR-YHB1-1: Characterization and genome analysis [J]. Chemosphere, 2019, 218: 1061-1070. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.11.145 [41] OREMLAND R S, STOLZ J F. Arsenic, microbes and contaminated aquifers [J]. Trends in Microbiology, 2005, 13(2): 45-49. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.12.002 [42] FANG Y J, CHEN M J, LIU C S, et al. Arsenic release from microbial reduction of scorodite in the presence of electron shuttle in flooded soil [J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2023, 126: 113-122. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2022.05.018 [43] KUDO K, YAMAGUCHI N, MAKINO T, et al. Release of arsenic from soil by a novel dissimilatory arsenate-reducing bacterium, Anaeromyxobacter sp. strain PSR-1 [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2013, 79(15): 4635-4642. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00693-13 [44] NIAZI N K, BURTON E D. Arsenic sorption to nanoparticulate mackinawite (FeS): An examination of phosphate competition[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2016, 218: 111-117. [45] ZHANG J, ZHOU W X, LIU B B, et al. Anaerobic arsenite oxidation by an autotrophic arsenite-oxidizing bacterium from an arsenic-contaminated paddy soil[J]. Environmental Science Technology, 2015, 49(10): 5956-5964. [46] RHINEE D, PHELPS C D, YOUNG L Y. Anaerobic arsenite oxidation by novel denitrifying isolates[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2006, 8(5): 899-908. [47] HOEFTMCCAN N S, BOREN A, HERNANDEZ-MALDONADO J, et al. Arsenite as an electron donor for anoxygenic photosynthesis: Description of three strains of Ectothiorhodospira from Mono Lake, California and Big Soda Lake, Nevada[J]. Life, 2016, 7(1): 1. -

下载:

下载: