-

邻苯二甲酸酯(PAEs)作为一种广泛使用的增塑剂,几十年来一直用于增强材料的柔韧性和耐用性[1]. 流行病学研究表明,邻苯二甲酸盐可能对人类内分泌系统造成不良影响[2 − 5],并造成生殖系统障碍[6 − 7]. 目前,全球邻苯二甲酸酯增塑剂市场约为每年550万t[8],大约有四分之一是在中国生产的[9].

在中国,城市化和现代化增加了室内合成材料的使用[10],人类在室内花费了超过一半的时间[11 − 12],室内环境质量已经引起越来越多的关注[13]. 室内灰尘是许多半挥发性和非挥发性物质的储存库,包括PAEs[14]. 由于PAEs的广泛使用[15 − 20],并且其与聚合物基体以较弱的范德华力结合[21 − 22],这使得它们在储存和使用中容易经过挥发、磨损等方式释放及转移到室内介质中[23]. 沉降的室内灰尘被认为是一种主要的暴露媒介和住宅污染的全球指标[24]. 室内灰尘中含有高浓度的几种PAEs,在每克室内灰尘中达到数十至数千微克[10],PAEs与室内颗粒结合,通过吸入、摄入或皮肤吸收的方式进入人体[25],并且发现人类某些过敏、哮喘和支气管阻塞的增加与灰尘中PAEs的浓度有关[26 − 27]. 此外,DEHP和BBP已被美国环保署分别归类为可能的人类致癌物[28]. PAEs的水平可能与经济和工业发展的区域差异以及特定的地理位置有关[29]. 在现有的研究中,多以家庭环境研究为主,关于东北地区PAEs的污染特征鲜有报道,之前已研究长春住宅中PAEs的含量[30]. 与家庭环境相比,宿舍空间狭小,人口密集,而目前很少有针对东北地区大学宿舍灰尘的研究.

本文以长春某高校学生宿舍内灰尘中的PAEs为主要研究对象,采用气相质谱色谱联用仪(GC-MS)检测PAEs的浓度,分析大学生宿舍中PAEs的污染特征以及影响污染水平的主要因素,探索灰尘中PAEs的可能来源,为东北地区室内环境中PAEs的暴露风险提供依据.

-

在2022年11月至2023年1月期间收集宿舍内的灰尘样品,采用一次性毛刷扫取灰尘样本. 在取样前使用的所有刷子都进行了预清洗,以去除制造或包装过程中的污染[13]. 采集样品时,尽量选择采集宿舍内多个位置,包括宿舍四周、床缝、暖气下方及橱柜的上方等[31]. 在采集过程中避免样品沾到水,除去灰尘样品中较大的颗粒和毛发等杂质,将同一宿舍多个区域的灰尘混合. 将采集好的样品装入铝箔袋内,在−20 ℃冰箱低温保存等待分析[13]. 在2023年8—9月,在107间宿舍中随机选择20间宿舍采集夏季灰尘样本,采集方法与上述做法一致. 同时记录了宿舍面积、装修时间、宿舍通风频率及每次通风时长等信息.

-

仪器:气质联用仪(Agilent 7890B/7000C);旋转蒸发仪(Xiande-5000ADQ);激光粒度分析仪(Malvern MS-2000);多参数分析仪(DZS-706F);超声波萃取仪(XM-P22H).

试剂:丙酮(分析纯)、二氯甲烷(色谱纯)、正己烷(色谱纯),6种PAEs的标准品:邻苯二甲酸二甲酯(DMP)、邻苯二甲酸二乙酯(DEP)、邻苯二甲酸二异丁酯(DiBP)、邻苯二甲酸二丁酯(DBP)、邻苯二甲酸丁苄酯(BBP)和邻苯二甲酸二(2-乙基己)酯(DEHP)浓度为1000 μg·mL−1(纯度大于98%).

-

用不锈钢筛对灰尘样品进行筛分,去除毛发和非降尘颗粒. 取0.050—0.100 g样品(精确到0.001 g),在20 mL的具塞试管中加入10 mL二氯甲烷,超声提取40 min. 此过程重复3次,将3次萃取液合并[31]. 使用旋转蒸发仪将提取液浓缩至近干燥. 浓缩液被转移到一个具有刻度的浓缩管,该管已用少量二氯甲烷润洗. 浓缩管中的溶液经二氯甲烷试剂定容至1 mL. 然后用 0.22 μm 有机微孔滤膜进行净化,转移至1.5 mL棕色自动进样瓶中,进行GC-MS分析.

-

气相色谱(Agilent Technologies 7890 B)和质谱(Agilent Technologies 7000C)用于测定 PAEs[32],使用熔融石英毛细管柱(CD-5MS;内径30 mm × 0.25 mm;薄膜厚度0.25 mm)在选择性离子监测模式下进行分离,将样品(1 μL)分流进样. 离子源和入口温度分别为230 °C和280 °C. 将烘箱温度保持在40 °C 2.0 min,以10 °C·min−1升至180 °C,然后在12.5 °C·min−1升至350 °C. 质谱以电子轰击电离源(EI),系统采用质谱检测器(MSD). DMP、DEP、DiBP和BBP的仪器定量限为0.2 ng·L−1,DBP和DEHP的仪器定量限分别为1.4 ng·L−1和3.6 ng·L−1.

-

本研究禁止使用塑料制品,使用的玻璃制品包括具塞试管、烧杯、浓缩管、玻璃注射器、巴斯德玻璃吸管以及旋转蒸发瓶. 使用前用自来水和超纯水冲洗,然后放入超声波清洗仪(KQ-500E, Kunshan Ultrasonic Inc., Kunshan, China)中20 min. 再用超纯水洗涤3次,60 °C烘箱中烘烤至没有水滴残留,最后用丙酮洗涤两次. 购买的PAEs标准溶液浓度为1000 μg·mL−1,体积为1 mL. 将1 mL标准溶液完全转移至100 mL棕色容量瓶中,以正己烷稀释定容,得到浓度为10 mg·L−1的混合标准储备液. 用移液管移取5 mL储备液于10 mL棕色容量瓶中,用正己烷稀释定容,得到浓度为5000 μg·L−1的标液,以此方法稀释依次得到浓度为1000、800 、500 、200、100 、50 、20 μg·L−1的标液. 各PAEs的校准曲线呈线性关系,r2 > 0.993. 对每批次12个样本分析3个方法空白和3个加标空白,所有空白与样品相同的程序分析,在方法空白中PAEs含量较低,占实际样品浓度的0.43%—6.38%,样品中PAEs的所有浓度均用空白值校正. DMP、DEP和DiBP的仪器检出限为0.2 ng·kg−1,DBP和DEHP的检出限为1.4 ng·kg−1和3.7 ng·kg−1. 标准加标回收实验表明,6种PAEs的回收率为85.6%—106.7%,满足实验要求.

-

灰尘中的PAEs通过摄入、吸入以及皮肤吸收途径进入人体并对健康产生危害,使用公式(1) —(3)计算PAEs的暴露量.

式中,EDIing为经口摄入的暴露量,μg·g−1·d−1;Cdust 是灰尘中PAEs的浓度,μg·g−1;f1 是室内暴露分数,学生在宿舍的暴露分数为0.55[33];Ring是灰尘摄入率,为0.03 g·d−1[14];BW 是体重(kg),根据中国人群暴露参数手册,体重采用男性66.1 kg,女性为57.8 kg[34].

式中,EDIinh为吸入途径的暴露量,μg·g−1·d−1;Rinh 是吸入率,男性为17.7 m3·d−1,女性为14.5 m3·d−1[34],PEF 是颗粒排放因子(1.36×106 m3·g−1)[25].

式中,EDIder为皮肤接触途径的暴露量,μg·g−1·d−1;f2 是皮肤中PAEs的吸收分数,DMP: 0.0004775,DEP: 0.0010255,DiBP: 0.000601,DBP: 0.000778,BBP: 0.0003535,DEHP: 0.000053;f3 是附着在皮肤上的灰尘,0.096 mg·cm−2[14];A 是暴露于灰尘的体表面积,男性体表面积为1.7 m2,女性为1.5 m2[34],冬季暴露分数为5%,夏季为25%[35].

使用危害指数(HI)法估算PAEs的累积风险评估,HI是单个PAE的危害商(HQ)之和[36 − 37],计算方法如式(4)和(5)所示,若HQ > 1,则该物质表现出非致癌风险. 在6种目标污染物中,BBP和DEHP具有致癌性,用CR代表致癌风险,计算方法如式(6)所示,若CR < 10−6,则致癌风险非常低;若CR在10−6—10−4范围内,则致癌风险为低;若CR在10−4—10−3范围内,则致癌风险为中度;若CR在10−3—1范围内,则为高;若CR > 1,则非常高[38].

式中,参考限值采用美国环保局推荐的RfD[39];CFS 是致癌物质的斜率因子(kg∙d∙mg−1),DEHP 的 CFS 值为 0.014 kg∙d∙mg−1 ,BBP 为 0.0019 kg∙d∙mg−1[40].

-

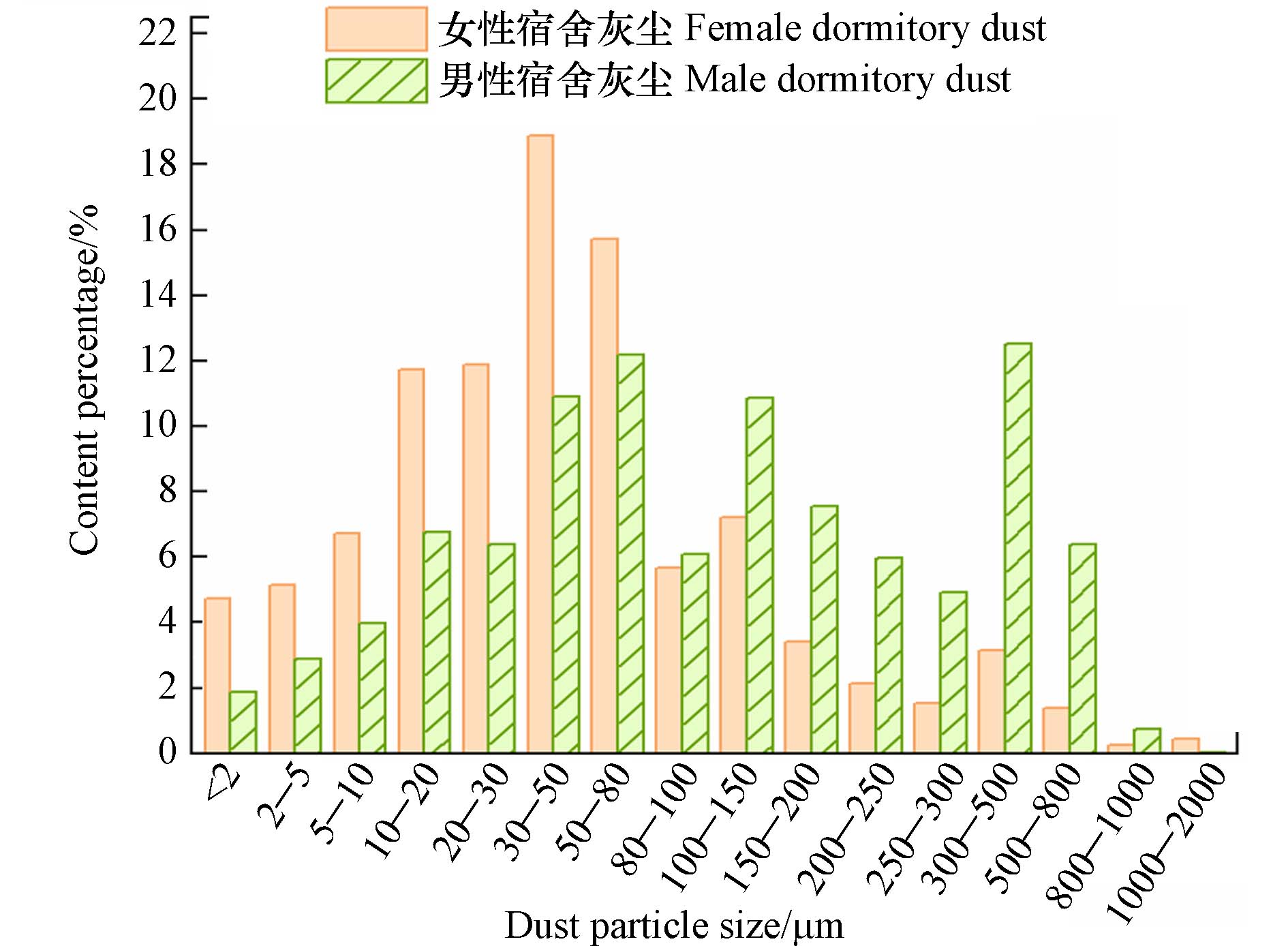

通过激光粒度仪分析,得出了宿舍内灰尘各粒径的含量百分比. 如图1所示,粒径小于30 μm的灰尘平均含量百分比为31.05%,30—50 μm的灰尘占比14.89%,粒径在50—100 μm之间的含量占比19.83%,100—200 μm粒径的灰尘占比14.53%,粒径为200—2000 μm占比19.71%. 男性宿舍粒径大于80 μm的灰尘含量百分比显著高于女性宿舍(P < 0.05),平均粒径为96.14 μm,女性宿舍中粒径小于80 μm的灰尘含量显著高于男性宿舍(P < 0.05),平均粒径为39.34 μm. 总体上,灰尘样本的平均粒径为67.74 μm,在灰尘组成中,粘粒占3.30%,粉粒占42.63%,砂砾占54.06%. 一般来说,小于63 μm的颗粒更容易粘附在皮肤上[41]. 更小颗粒的灰尘会悬浮在空气中,这些灰尘成分中的PAEs可以通过手-口摄入和吸入呼吸系统转移到人体中,对健康构成风险. 小粒径的灰尘颗粒具有更强的吸附能力,这可以通过每单位质量更细颗粒的更大表面积来解释[42].

-

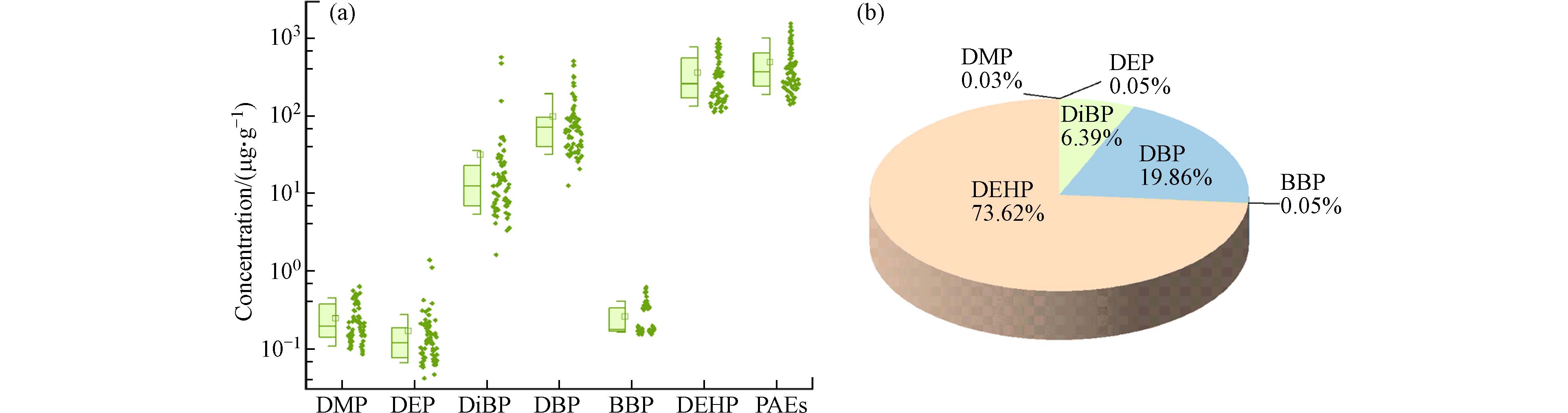

宿舍灰尘中PAEs的污染水平如图2(a)所示,灰尘中6种PAEs的总含量在141.94—1561.06 μg·g−1之间,平均值和中值分别为494.19 μg·g−1和372.56 μg·g−1. 如图2(b)所示,室内灰尘中最主要PAE是DEHP,这是由于DEHP是在各种领域中最常使用的PAE [29],并且DEHP饱和蒸气压较低,更容易被灰尘吸收. 其次是DBP和DiBP,分别约占总PAEs的19.86%和6.39%,二者常用于个人护理品、印刷油墨、粘合剂和纺织品等[43],而DMP和DEP相对分子量较小,饱和蒸气压较高,常以气态形式存在,在灰尘中的含量较低[44].

-

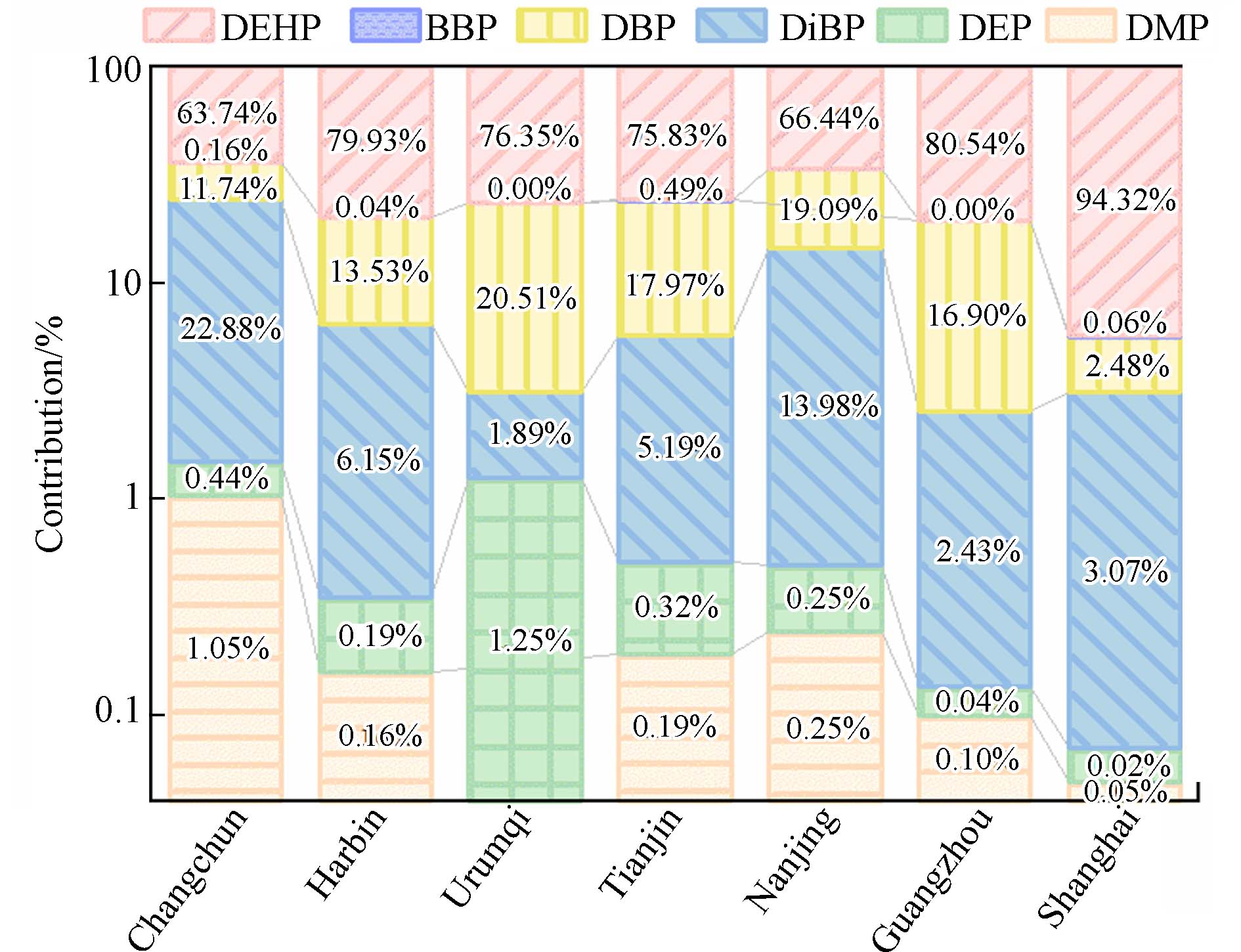

比较近几年多地区PAEs的浓度和组成,如表1所示,大多数研究来自南方地区[14,45 − 54]以及华北地区[10,14,27,31,43,55 − 57],且样本采集时间较早,多数研究以家庭住宅灰尘为介质[58 − 59]. 在三项调查了大学生宿舍灰尘PAEs的研究中,在我们的研究中DEHP的平均浓度(364.5 μg·g−1)高于南京大学生宿舍(135 μg·g−1)[47]以及北京宿舍中DEHP的浓度(211 μg·g−1)[31],与哈尔滨大学生宿舍中DEHP的浓度相当(355 μg·g−1),低于沈阳宿舍DEHP的浓度(430 μg·g−1)[15]. 并且南京和广州室内PAEs的浓度似乎有下降趋势[14,46 − 50],在重庆和成都,PAEs浓度显著高于其他地区[51 − 52],在北京和西安[9,10,14,27,31,43,59],PAEs浓度略有上升,在西安室内DiBP和DBP的浓度显著高于其他地区,DEHP的浓度与重庆相当. 在东北地区缺少相同城市的研究,在长春家庭住宅灰尘中测得的DEHP浓度低于哈尔滨及齐齐哈尔的浓度[14 − 15,30]. 比较了采样时间较近的研究中PAEs的组成,如图3所示,与长春住宅中PAEs的组成相比,宿舍灰尘6种PAEs中DEHP占比更高,且DBP比DiBP贡献更高. 与其他北方城市相比,长春宿舍中DiBP占比较高,与哈尔滨宿舍相当[15],高于乌鲁木齐和天津室内DiBP的贡献[57],DBP处于中等水平,而DMP、DEP的贡献较低,仅占0.03%和0.05%. 与南方城市相比,上海室内灰尘中DEHP占比相当大[45],在广州和上海室内灰尘中的DiBP显著低于本研究,而南京宿舍中DMP、DEP和DiBP的贡献均高于长春宿舍[47]. 从整体来看,长春宿舍灰尘中PAEs的处于中等水平.

-

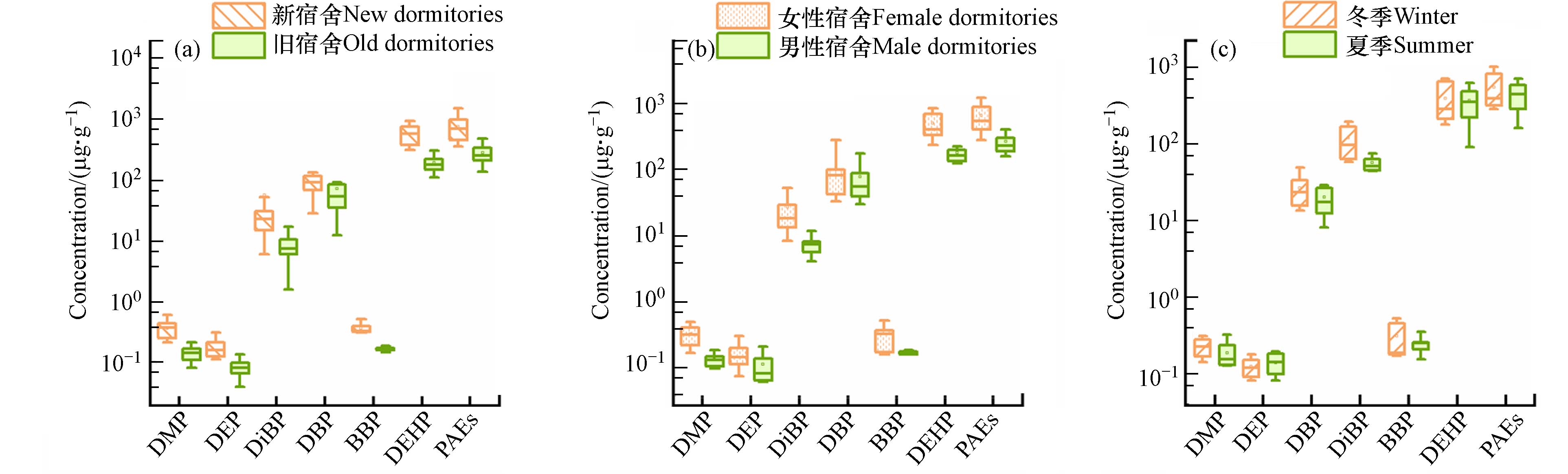

根据图4(a)所示,在56间女性宿舍检测到六种PAEs的浓度范围为198.73—1561.1 μg·g−1,平均浓度是669.0 μg·g−1,51间男性宿舍PAEs总浓度范围在141.94—650.33 μg·g−1. 女性宿舍中的DMP、DEP、DiBP、BBP和DEHP均显著高于男性宿舍(P < 0.05). 在女性宿舍发现了更多的邻苯二甲酸酯来源,包括个人护理品、衣服和女性卫生用品等,这与Duan等在大学宿舍中的发现一致[60]. 与男性相比,女性使用个人护理品频率更高[20, 61],在Ficheux等的研究中女性平均每天使用12种个人护理品,而男性使用6种[62]. 此外,Zhang等发现女性使用毛巾的PAEs暴露量高于男性,这也与使用个人护理品的情况有关[32]. DiBP和DBP是纺织品中广泛使用的添加剂,衣物和空气之间存在半挥发性有机化合物(SVOCs)的分配行为,会向室内环境中排放PAEs[37, 63],女性宿舍中更多的衣物也可能增加环境中PAEs的浓度. 此外,宿舍的灰尘中PAEs的浓度差异可能与其粒径分布有关. 灰尘颗粒物的粒径大小能够影响灰尘颗粒本身与环境中共存污染物的相互作用. 一般而言,灰尘的粒径越小,其吸附能力越强[64]. Wang等分析了不同粒径的室内外灰尘中PAEs的含量,发现< 63 μm的灰尘颗粒物具有最高的PAEs的分布因子[54]. 在灰尘中多环芳烃与重金属的粒径分布也检测到这一特征[65 − 66]. 因此,在男女宿舍中所识别的灰尘粒径的差异部分也解释了女性宿舍中PAEs污染程度更高的现象.

本研究包括35间装修时间在两年以内新宿舍,以及72间装修时间超过五年的旧宿舍,如图4(b)所示,新装修宿舍中PAEs的总浓度平均值为776.29 μg·g−1,旧宿舍中PAEs的总浓度平均值为287.78 μg·g−1. 在6种PAEs中,除DiBP以外的所有PAEs在新装修宿舍中的浓度均显著高于旧宿舍(P < 0.05). 在新装修宿舍中,装修程度更高,研究表明均室内装修材料中PAEs的污染较为普遍[67],主要来源于PVC材料、涂料等,并且从家具板材、塑料制品中释放的污染可能是长期存在的. 此外,新装修宿舍的面积更小,Zhao等发现DEHP的浓度与教室的面积显著负相关,这可能也是新宿舍比旧宿舍PAEs浓度更高的原因[68].

为了比较季节变化对PAEs的影响,使用配对的冬季和夏季灰尘样本进行对比. 如图4(c)所示,在夏季,6种PAEs的浓度均有所下降. 根据居住者报告的宿舍内通风频率和时间统计,在冬季有34间宿舍通风频率大于一天一次,44间通风频率为一天一次,29间通风频率少于一天一次,平均每次通风时间为15 min. 而在夏季,通风频率和时间显著提高,在采样宿舍中,所有宿舍都保持每天通风,有35%的宿舍窗户保持一直敞开状态,每天持续通风24 h. 有研究表明,室外环境中PAEs的浓度普遍低于室内环境,Ouyang 等的研究中测量的三种室内环境中15种PAEs平均浓度为22.1 μg·m−3,而室外空气中15种PAEs平均浓度为3.62 μg·m−3,二者相差一个数量级[69]. 南京室内住宅灰尘中6种PAEs的平均浓度为139.1 μg·g−1,而室外灰尘PAEs的浓度约为14.1 μg·g−1[24]. 因此增加通风时间可以降低室内环境中PAEs的累积[70]. 此外,研究表明,增塑剂从PVC板扩散到表面,在PVC板表层与空气之间发生对流传质,较高的温度可以增加分子内能,分子扩散和对流速率也会增加[71],然而温度的升高虽然会增加源排放率,也会导致尘-气分配系数(Kd)的降低[52],Pei等发现温度并非通过排放率来影响灰尘中PAEs的浓度,而是通过Kd[57].

-

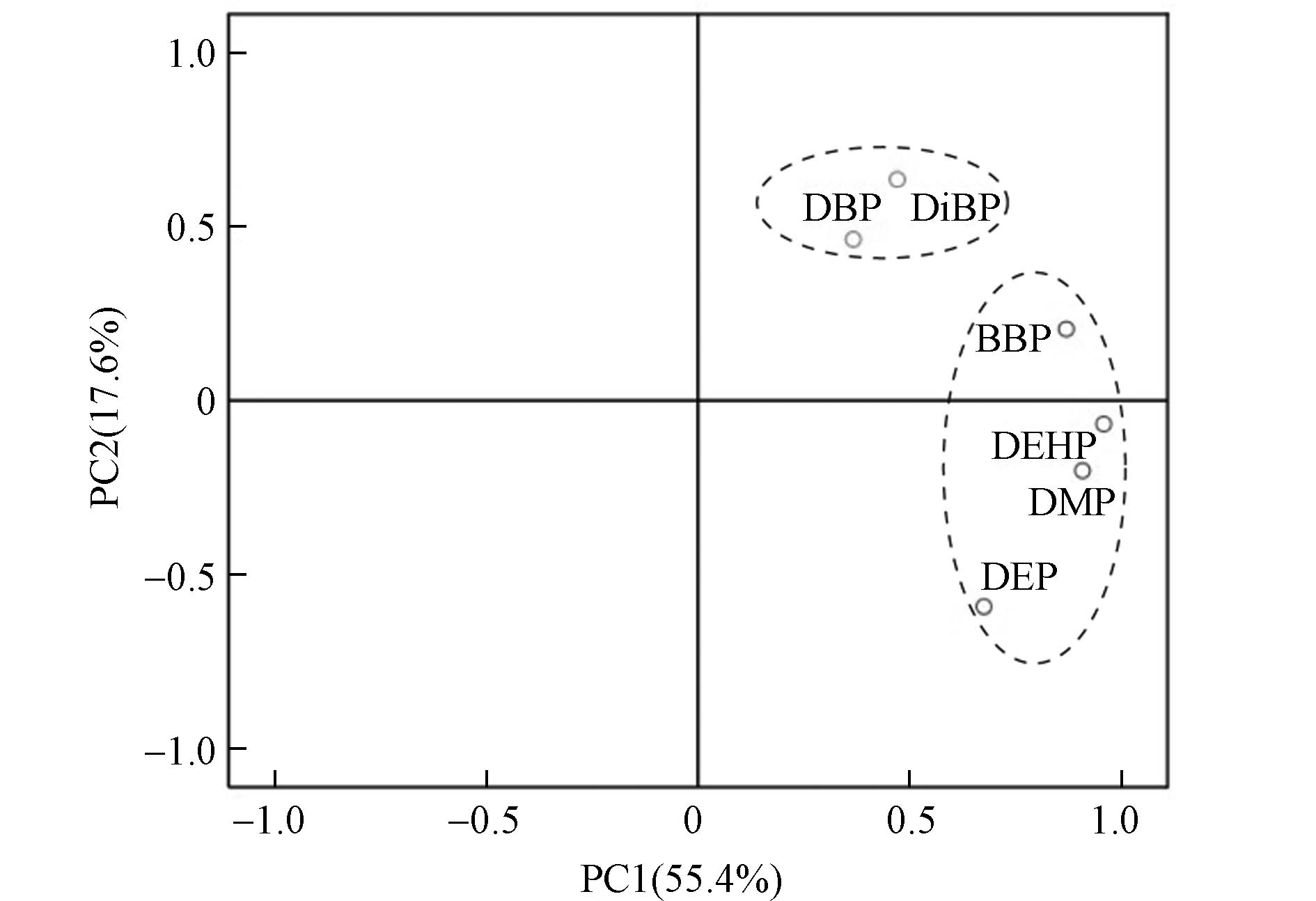

使用主成分分析(PCA)来探索宿舍环境灰尘中PAEs的可能来源[72]. 使用IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0进行分析. 以107份粉尘样品中6种PAEs的浓度为主动变量,通过主成分分析为所有样本提取了两个主要因子,因子载荷如图5所示,PC1和PC2分别解释了总体方差的55.4%和17.6%,累积贡献率为73.0%. 根据每个PAE的得分分成两组,第一组与PC1呈显著正相关,包括DMP、DEP、BBP和DEHP,其中DEHP在PC1上载荷最高,为0.960. DMP和DEP广泛用于化妆品中[14],DEHP和BBP主要作为增塑剂使用在塑料制品和PVC中以提升产品的柔韧性[60],因此第一主成分反映了室内灰尘中的PAEs可能来自于化妆品以及塑料制品. DiBP在第二成分上载荷最高,为0.636,DiBP是粘合剂、纺织品添加剂中的常用物质[73],因此第二主成分主要源于室内纺织品及日常生活品.

-

PAEs对人体具有多种毒性,进行健康风险评估对于了解PAEs的污染情况以及保护人类健康极为重要. 表2中显示了暴露于新宿舍、旧宿舍、男性宿舍、女性宿舍以及冬季和夏季灰尘中PAEs的非致癌风险和致癌风险. 结果显示所有宿舍灰尘中PAEs的非致癌风险均小于1,在3种暴露途径中,摄入途径对灰尘中PAEs的健康风险贡献最大,显著高于吸入和皮肤接触途径(P < 0.05). DEHP和BBP的总致癌风险在3.67

$ \times $ 10−7—5.13$ \times $ 10−6之间,有32%的宿舍灰尘中的PAEs的致癌风险小于10−6,显示为非常低的致癌风险,68%的宿舍灰尘中PAEs的致癌风险在10−6—10−4之间,显示为低风险. 其中新装修宿舍灰尘中的PAEs的HI及CR值均高于旧宿舍,女性宿舍灰尘中的PAEs导致的致癌和非致癌风险均高于男性宿舍. 此外,在冬季宿舍灰尘的健康风险高于夏季. DEHP的致癌风险显著高于BBP(P < 0.05),应持续关注室内环境中DEHP的污染情况. DEHP通过诱导内分泌系统生物标志物和炎性细胞因子的增加来干扰肿瘤坏死因子α [74 − 76],而持续暴露于高水平的DEHP可能会导致不可逆转的健康影响,如生殖毒性和发育毒性[77 − 78]. 因此,不能忽视DEHP长期暴露对人体的健康影响. 灰尘是暴露于DEHP的重要介质,且DEHP的污染广泛存在,应加强对其生产和使用的管理[79]. 为了降低宿舍中PAEs的健康风险,大学生应该及时清理不必要的塑料制品,并增加通风频率增加室外空气的交换以减少室内PAEs的浓度,由于DEHP相对分子量较大,其广泛存在于尘相中,经常进行地面清洁,清扫擦除灰尘有利于减少DEHP的暴露风险. -

1)PAEs在长春宿舍灰尘中广泛存在,由于DEHP、DiBP和DBP的高使用量以及其物理化学性质使其在室内灰尘中含量较高. 长春宿舍灰尘中PAEs的浓度低于长春住宅灰尘,与其他地区相比处于中等水平.

2)新装修宿舍PAEs的浓度显著高于旧宿舍,女性宿舍PAEs浓度高于男性宿舍,季节因素也会影响PAEs的污染水平,夏季PAEs浓度更低. 基于PCA的主成分分析表明,PAEs主要来源于室内的个人护理品、塑料制品及纺织品.

3)由宿舍内灰尘中PAEs导致的非致癌风险在安全阈值内,在摄入、吸入及皮肤吸收3种途径中,摄入途径会导致最高的健康风险. 致癌物BBP和DEHP致癌风险为低风险. 建议增加通风时间,并及时清理不必要的塑料制品以减少宿舍环境中PAEs的暴露风险.

长春市大学生宿舍灰尘中邻苯二甲酸酯暴露及健康风险

Phthalate exposure and health risks from dust in university dormitories in Changchun City

-

摘要: 内分泌干扰物邻苯二甲酸酯(phthalic acid esters,PAEs)在室内环境中广泛存在. 室内灰尘作为一种复杂的环境载体,是许多污染物的源和汇,PAEs吸附在室内灰尘颗粒中可能会带来潜在的健康风险. 为了补充东北地区室内灰尘中PAEs的污染信息,并探索PAEs的污染特征和风险水平,在长春高校宿舍采集了107份冬季灰尘样本和20份夏季样本,分析了灰尘中PAEs的含量,并进一步研究了PAEs的分布特征、影响因素、潜在来源以及健康风险. 结果表明,在冬季,宿舍灰尘中PAEs的浓度为141.94—1561.06 μg·g−1,其中邻苯二甲酸二(2-乙基己)酯(DEHP)是最主要的PAEs污染物,平均贡献率为73.62%. 装修时间、个人因素以及季节变化都会影响宿舍内PAEs的含量,其中新装修宿舍灰尘中PAEs的含量显著高于旧宿舍,女性宿舍灰尘中PAEs的浓度显著高于男性宿舍,配对的冬季灰尘中PAEs的浓度高于夏季. 宿舍灰尘中PAEs的主要来源可能是个人护理品、塑料制品以及纺织品. PAEs的非致癌风险小于1,在可接受范围内,摄入途径是暴露于PAEs的主要途径. 致癌性PAEs,邻苯二甲酸丁苄酯(BBP)和DEHP致癌风险为低风险,DEHP的致癌风险显著高于BBP.Abstract: The endocrine disruptor phthalic acid esters (PAEs) are widespread in the indoor environment. As a complex environmental carrier, indoor dust is a source and sink of many pollutants, and PAEs adsorbed in indoor dust particles may pose potential health risks. In order to supplement the pollution information of PAEs in indoor dust in Northeast China and to explore the pollution characteristics and risk levels of PAEs, 107 winter dust samples and 20 summer samples were collected from university dormitories in Changchun. The levels of PAEs in the dust were analyzed, and the distribution characteristics, influencing factors, potential sources, and health risks of PAEs were further investigated. The results showed that in winter, the concentrations of PAEs in dormitory dust ranged from 141.94 μg·g−1 to 1561.06 μg·g−1, with bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) being the most dominant PAEs pollutant with an average contribution of 73.62%. The time of renovation, personal factors, and seasonal changes all affected the levels of PAEs in the dormitories, in which the levels of PAEs in dust in the newly renovated dormitories were significantly higher than those in the old dormitories, the concentrations of PAEs in dust in the female dormitories were significantly higher than those in the male dormitories, and the concentrations of PAEs in the dust in the paired winter months were higher than those in the summer months. The main sources of PAEs in dormitory dust may be personal care products, plastic products, and textiles. The noncarcinogenic risk of PAEs was less than 1, which is within the acceptable range, and the ingestion route was the main route of exposure to PAEs. For carcinogenic PAEs, the carcinogenic risk of benzyl butyl phthalate (BBP) and DEHP was low, and the carcinogenic risk of DEHP was significantly higher than that of BBP.

-

Key words:

- phthalates /

- dormitory dust /

- pollution characteristics /

- risk assessment.

-

-

表 1 中国城市室内灰尘中PAEs的浓度

Table 1. Concentrations of PAEs in indoor dust in Chinese cities

城市

City采样地点

Sampling site采样时间

Sampling time浓度/(μg·g−1)

Concentration参考文献

ReferencesDMP DEP DiBP DBP BBP DEHP 上海 家庭 2010 0.2 0.4 33.6 26.9 0.2 319 [14] 家庭 2017 2.87 1.49 32.5 56.46 0.78 485.17 [45] 南京 家庭 2014—2015 1.91 0.22 — 99.6 0.77 557 [46] 家庭 2016 0.97 0.6 51.5 152.7 — 397.3 [47] 宿舍 2016 0.5 0.5 28.4 38.8 — 135 广州 公寓 2007 1.73 1.42 38.9 53.5 1.23 858 [48] 家庭 2010 0.3 0.2 11.1 11.6 0.2 146 [14] 家庭 2016—2019 0.82 5.01 42.4 20.5 — 301 [49] 家庭 2018 0.44 0.16 10.7 74.5 ND 355 [50] 重庆 家庭 2014—2015 6 16 181.6 180 0.8 1892 [51] 成都 家庭 2020 0.63 0.78 82.9 152.93 1.04 564.16 [52] 香港 家庭 2010 8.09 8.34 9.94 17.9 8.22 690 [53] 台湾 幼儿园 2012—2014 ND ND 3.6 9.2 ND 571.8 [54] 家庭 2012—2014 ND ND 1.7 4.9 ND 298.3 学校 2012—2014 ND ND ND 7.9 2 860.3 济南 家庭 2010 0.06 0.1 10.4 9.3 0.1 98.2 [14] 北京 家庭 2010 0.7 0.4 12.6 18.9 0.6 156 [14] 家庭 2010—2011 — ND ND 68.8 — 231 [10] 幼儿园 2012 — — 166 124 — 333 [27] 家庭 2013 ND ND 39 63 ND 460 [43] 宿舍 2017 — — 12.1 39.8 66.6 211 [31] 天津 家庭 2013—2016 — 0.56 43.1 230.11 0.91 457.38 [55] 家庭 2013—2016 — 0.58 49.6 243.74 0.46 574.24 [56] 家庭 2016—2017 0.64 1.08 17.36 60.09 1.63 253.56 [57] 石河子 家庭 2017 1.6 0.81 24.9 246 0.29 539 [58] 家庭 2017 0.79 0.61 16.4 261 0.95 697 西安 家庭 2012—2013 5.66 — 900.98 447.78 — 798.61 [9] 家庭 2019 75.4 — 527.5 1256.8 — 1787.9 [59] 哈尔滨 宿舍 2014 0.71 0.84 27.3 60.1 0.18 355 [15] 家庭 2014 1.33 0.89 17.4 66.6 0.16 521 [15] 齐齐哈尔 家庭 2010 0.1 1.5 26 21.9 0.2 348 [14] 沈阳 宿舍 2014 0.56 0.71 23.1 33 0.23 430 [15] 长春 家庭 2019 3.42 1.43 74.86 38.4 0.52 208.5 [30] 保定 宿舍 2014 0.35 0.6 13.1 33.1 0.076 79.7 [15] 乌鲁木齐 家庭 2010 0.5 0.8 32.8 170 0.4 563 [14] 家庭 2016-2017 0 9.96 15.06 163.75 ND 609.51 [57] ND,未检出. ND, not detected. —,无数据. —, no data is available. 表 2 暴露于大学宿舍灰尘中PAEs的健康风险

Table 2. Health risks of exposure to PAEs from dust in university dormitories

数值

Values新宿舍

New dormitories旧宿舍

Old dormitories男性宿舍

Male dormitories女性宿舍

Female dormitories冬季

Winter夏季

SummerHIing 最小值 4.41 $ \times $ 1.87 $ \times $ 1.87 $ \times $ 2.81 $ \times $ 1.87 $ \times $ 1.01 $ \times $ 平均值 1.35 $ \times $ 3.77 $ \times $ 3.63 $ \times $ 1.52 $ \times $ 8.73 $ \times $ 6.12 $ \times $ 最大值 2.18 $ \times $ 1.13 $ \times $ 8.55 $ \times $ 2.18 $ \times $ 2.18 $ \times $ 1.93 $ \times $ HIinh 最小值 1.06 $ \times $ 5.83 $ \times $ 5.83 $ \times $ 6.72 $ \times $ 5.83 $ \times $ 4.62 $ \times $ 平均值 4.35 $ \times $ 1.22 $ \times $ 1.01 $ \times $ 3.78 $ \times $ 2.71 $ \times $ 1.92 $ \times $ 最大值 6.89 $ \times $ 6.42 $ \times $ 2.57 $ \times $ 6.89 $ \times $ 6.89 $ \times $ 5.37 $ \times $ HIda 最小值 1.84 $ \times $ 8.77 $ \times $ 8.77 $ \times $ 1.32 $ \times $ 8.77 $ \times $ 5.63 $ \times $ 平均值 9.73 $ \times $ 2.13 $ \times $ 2.32 $ \times $ 8.72 $ \times $ 5.64 $ \times $ 3.83 $ \times $ 最大值 3.62 $ \times $ 5.15 $ \times $ 5.34 $ \times $ 3.62 $ \times $ 3.62 $ \times $ 1.03 $ \times $ CRBBP 最小值 1.76 $ \times $ 6.58 $ \times $ 7.23 $ \times $ 6.58 $ \times $ 6.58 $ \times $ 4.87 $ \times $ 平均值 3.82 $ \times $ 1.12 $ \times $ 1.08 $ \times $ 3.28 $ \times $ 2.77 $ \times $ 1.42 $ \times $ 最大值 6.64 $ \times $ 2.03 $ \times $ 2.03 $ \times $ 6.64 $ \times $ 6.64 $ \times $ 4.58 $ \times $ CRDEHP 最小值 7.91 $ \times $ 3.67 $ \times $ 3.67 $ \times $ 6.87 $ \times $ 3.67 $ \times $ 2.11 $ \times $ 平均值 3.52 $ \times $ 9.33 $ \times $ 8.76 $ \times $ 2.62 $ \times $ 1.52 $ \times $ 8.32 $ \times $ 最大值 5.13 $ \times $ 2.17 $ \times $ 1.88 $ \times $ 5.13 $ \times $ 5.13 $ \times $ 3.35 $ \times $ -

[1] BU Z M, MMEREKI D, WANG J H, et al. Exposure to commonly-used phthalates and the associated health risks in indoor environment of urban China[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 658: 843-853. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.260 [2] BANG D Y, LEE I K, LEE B M. Toxicological characterization of phthalic acid[J]. Toxicological Research, 2011, 27(4): 191-203. doi: 10.5487/TR.2011.27.4.191 [3] EJAREDAR M, NYANZA E C, TEN EYCKE K, et al. Phthalate exposure and childrens neurodevelopment: A systematic review[J]. Environmental Research, 2015, 142: 51-60. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2015.06.014 [4] CHIANG C, LEWIS L R, BORKOWSKI G, et al. Exposure to di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate and diisononyl phthalate during adulthood disrupts hormones and ovarian folliculogenesis throughout the prime reproductive life of the mouse[J]. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 2020, 393: 114952. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2020.114952 [5] HUANG S Y, QI Z H, MA S T, et al. A critical review on human internal exposure of phthalate metabolites and the associated health risks[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 279: 116941. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116941 [6] MÍNGUEZ-ALARCÓN L, BURNS J, WILLIAMS P L, et al. Urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations during four windows spanning puberty (prepuberty through sexual maturity) and association with semen quality among young Russian men[J]. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 2022, 243: 113977. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2022.113977 [7] LI Y Y, ZHENG N, LI Y, et al. Exposure of childbearing-aged female to phthalates through the use of personal care products in China: An assessment of absorption via dermal and its risk characterization[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2022, 807: 150980. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150980 [8] HEALTH N I O P, GKRILLAS A, DIRVEN H, et al. Risk assessment of phthalates based on aggregated exposure from foods and personal care products and comparison with biomonitoring data[J]. EFSA Journal. European Food Safety Authority, 2020, 18(Suppl 1): e181105. [9] WANG X K, TAO W, XU Y, et al. Indoor phthalate concentration and exposure in residential and office buildings in Xi'an, China[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2014, 87: 146-152. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.01.018 [10] WANG L X, GONG M Y, XU Y, et al. Phthalates in dust collected from various indoor environments in Beijing, China and resulting non-dietary human exposure[J]. Building and Environment, 2017, 124: 315-322. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2017.08.006 [11] LI Z M, ZHENG N, AN Q R, et al. Impact of environmental factors and bacterial interactions on dust mite allergens in different indoor dust[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2022, 844: 157177. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157177 [12] LAO J Y, RUAN Y F, LEUNG K M Y, et al. Review on age-specific exposure to organophosphate esters: Multiple exposure pathways and microenvironments[J]. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 2023, 53(7): 803-826. doi: 10.1080/10643389.2022.2087428 [13] ZHU Q Q, JIA J B, ZHANG K G, et al. Phthalate esters in indoor dust from several regions, China and their implications for human exposure[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 652: 1187-1194. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.326 [14] GUO Y, KANNAN K. Comparative assessment of human exposure to phthalate esters from house dust in China and the United States[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2011, 45(8): 3788-3794. [15] LI H L, SONG W W, ZHANG Z F, et al. Phthalates in dormitory and house dust of northern Chinese cities: Occurrence, human exposure, and risk assessment[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2016, 565: 496-502. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.04.187 [16] MALARVANNAN G, ONGHENA M, VERSTRAETE S, et al. Phthalate and alternative plasticizers in indwelling medical devices in pediatric intensive care units[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2019, 363: 64-72. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.09.087 [17] ZHANG L E, RUAN Z L, JING J J, et al. High-temperature soup foods in plastic packaging are associated with phthalate body burden and expression of inflammatory mRNAs: A dietary intervention study[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2022, 56(12): 8416-8427. [18] BABICH M A, BEVINGTON C, DREYFUS M A. Plasticizer migration from children’s toys, child care articles, art materials, and school supplies[J]. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, 2020, 111: 104574. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2019.104574 [19] HSIEH C J, CHANG Y H, HU A R, et al. Personal care products use and phthalate exposure levels among pregnant women[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 648: 135-143. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.149 [20] STUCHLÍK FIŠEROVÁ P, MELYMUK L, KOMPRDOVÁ K, et al. Personal care product use and lifestyle affect phthalate and DINCH metabolite levels in teenagers and young adults[J]. Environmental Research, 2022, 213: 113675. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.113675 [21] NET S, SEMPÉRÉ R, DELMONT A, et al. Occurrence, fate, behavior and ecotoxicological state of phthalates in different environmental matrices[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2015, 49(7): 4019-4035. [22] 朱冰清, 胡冠九, 纪轩禹, 等. 江苏省自来水中邻苯二甲酸酯的污染特征及风险评估[J]. 环境化学, 2023, 42(8): 2586-2593. doi: 10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2022031105 ZHU B Q, HU G J, JI X Y, et al. Pollution characteristics and health risk assessment of phthalate esters in tap water from Jiangsu Province[J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2023, 42(8): 2586-2593 (in Chinese). doi: 10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2022031105

[23] PRASAD B, PRASAD K S, DAVE H, et al. Cumulative human exposure and environmental occurrence of phthalate esters: A global perspective[J]. Environmental Research, 2022, 210: 112987. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.112987 [24] ZHANG Q, LU X M, ZHANG X L, et al. Levels of phthalate esters in settled house dust from urban dwellings with young children in Nanjing, China[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2013, 69: 258-264. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.12.029 [25] KANG Y, MAN Y B, CHEUNG K C, et al. Risk assessment of human exposure to bioaccessible phthalate esters via indoor dust around the Pearl River Delta[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2012, 46(15): 8422-8430. [26] BORNEHAG C G, SUNDELL J, WESCHLER C J, et al. The association between asthma and allergic symptoms in children and phthalates in house dust: A nested case-control study[J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2004, 112(14): 1393-1397. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7187 [27] WANG L X, WU Z X, GONG M Y, et al. Non-dietary exposure to phthalates for pre-school children in kindergarten in Beijing, China[J]. Building and Environment, 2020, 167: 106438. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2019.106438 [28] WANG W, LEUNG A O W, CHU L H, et al. Phthalates contamination in China: Status, trends and human exposure-with an emphasis on oral intake[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2018, 238: 771-782. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.02.088 [29] GAO D W, LI Z, WANG H, et al. An overview of phthalate acid ester pollution in China over the last decade: Environmental occurrence and human exposure[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 645: 1400-1409. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.093 [30] 侯胜男. 灰尘中重金属和邻苯二甲酸酯复合污染特征及毒理学效应[D]. 北京: 中国科学院大学, 2021. HOU S N. Characteristics and toxicological effects of combined pollution of heavy metals and phthalates in dust[D]. Beijing: University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2021 (in Chinese).

[31] QU M N, WANG L X, LIU F, et al. Characteristics of dust-phase phthalates in dormitory, classroom, and home and non-dietary exposure in Beijing, China[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2021, 28(28): 38159-38172. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-13347-1 [32] ZHANG W H, ZHENG N, WANG S J, et al. Characteristics and health risks of population exposure to phthalates via the use of face towels[J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2023, 130: 1-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2022.10.016 [33] CHEN Y, LV D, LI X H, et al. PM2.5-bound phthalates in indoor and outdoor air in Beijing: Seasonal distributions and human exposure via inhalation[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2018, 241: 369-377. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.05.081 [34] 中华人民共和国生态环境部. 中国人群暴露参数手册(成人). 北京: 中国环境科学出版社;2013. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. Exposure Factors Handbook of Chinese Population (Adults). Beijing: China Environmental Science Press;2013(in Chinese).

[35] 李佳. 室内降尘与个人护理品中邻苯二甲酸酯的分析研究[D]. 哈尔滨: 哈尔滨工业大学, 2014. LI J. The analysis of phthalates in indoor dustand personalcare products[D]. Harbin: Harbin Institute of Technology, 2014 (in Chinese).

[36] BENSON R. Hazard to the developing male reproductive system from cumulative exposure to phthalate esters—Dibutyl phthalate, diisobutyl phthalate, butylbenzyl phthalate, diethylhexyl phthalate, dipentyl phthalate, and diisononyl phthalate[J]. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, 2009, 53(2): 90-101. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2008.11.005 [37] LI H L, MA W L, LIU L Y, et al. Phthalates in infant cotton clothing: Occurrence and implications for human exposure[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 683: 109-115. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.132 [38] LI Y, YAN H Q, LI X Q, et al. Presence, distribution and risk assessment of phthalic acid esters (PAEs) in suburban plastic film pepper-growing greenhouses with different service life[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2020, 196: 110551. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110551 [39] USEPA. Noncancer assessment. U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC[EB/OL]. [2023-5-19]. [40] USEPA. Regional Screening Level (RSL) Summary Table. U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC[EB/OL]. [2023-5-19]. [41] CHOATE L M, RANVILLE J F, BUNGE A L, et al. Dermally adhered soil: 1. Amount and particle-size distribution[J]. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 2006, 2(4): 375-384. doi: 10.1002/ieam.5630020409 [42] WEISS J M, GUSTAFSSON A, GERDE P, et al. Daily intake of phthalates, MEHP, and DINCH by ingestion and inhalation[J]. Chemosphere, 2018, 208: 40-49. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.05.094 [43] HUANG S Y, MA S T, WANG D W, et al. National-scale urinary phthalate metabolites in the general urban residents involving 26 provincial capital cities in China and the influencing factors as well as non-carcinogenic risks[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2022, 838: 156062. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156062 [44] MENG Z Y, WANG L X, CAO B K, et al. Indoor airborne phthalates in university campuses and exposure assessment[J]. Building and Environment, 2020, 180: 107002. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107002 [45] 杨其帆, 沈冰, 蔡菁婷, 等. 上海市室内灰尘中邻苯二甲酸酯分布及人群暴露风险评估[J]. 上海预防医学, 2022, 34(3): 247-251,264. YANG Q F, SHEN B, CAI J T, et al. Distribution and exposure assessment of phthalic acid esters(PAEs) in indoor dust of Shanghai[J]. Shanghai Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2022, 34(3): 247-251,264 (in Chinese).

[46] HE R W, LI Y Z, XIANG P, et al. Organophosphorus flame retardants and phthalate esters in indoor dust from different microenvironments: Bioaccessibility and risk assessment[J]. Chemosphere, 2016, 150: 528-535. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.10.087 [47] XU S, LI C. Phthalates in house and dormitory dust: Occurrence, human exposure and risk assessment[J]. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2021, 106(2): 393-398. doi: 10.1007/s00128-020-03058-7 [48] LAN Q, CUI K Y, ZENG F, et al. Characteristics and assessment of phthalate esters in urban dusts in Guangzhou city, China[J]. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 2012, 184(8): 4921-4929. doi: 10.1007/s10661-011-2312-3 [49] SHI Y M, LIU X T, XIE Q T, et al. Plastic additives and personal care products in South China house dust and exposure in child-mother pairs[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 281: 116347. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.116347 [50] HUANG C, ZHANG Y J, LIU L Y, et al. Exposure to phthalates and correlations with phthalates in dust and air in South China homes[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 782: 146806. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146806 [51] BU Z M, ZHANG Y P, MMEREKI D, et al. Indoor phthalate concentration in residential apartments in Chongqing, China: Implications for preschool children’s exposure and risk assessment[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2016, 127: 34-45. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.12.010 [52] 曾迪娅, 陈志伟, 张彬. 家庭灰尘中邻苯二甲酸酯的经皮风险评价[J]. 环境科学与技术, 2021, 44(12): 185-193. ZENG D Y, CHEN Z W, ZHANG B. Dermal risk assessment of PAEs contained in household dust[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2021, 44(12): 185-193 (in Chinese).

[53] WANG W, WU F Y, HUANG M J, et al. Size fraction effect on phthalate esters accumulation, bioaccessibility and in vitro cytotoxicity of indoor/outdoor dust, and risk assessment of human exposure[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2013, 261: 753-762. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.04.039 [54] HUANG C N, CHIOU Y H, CHO H B, et al. Children’s exposure to phthalates in dust and soil in Southern : A study following the phthalate incident in 2011[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 696: 133685. [55] ZHU C Q, SUN Y X, ZHAO Y X, et al. Associations between Children’s asthma and allergic symptoms and phthalates in dust in metropolitan Tianjin, China[J]. Chemosphere, 2022, 302: 134786. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.134786 [56] SUN Y X, ZHANG Q N, HOU J, et al. Exposure of phthalates in residential buildings and its health effects[J]. Procedia Engineering, 2017, 205: 1901-1904. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2017.10.286 [57] PEI J J, SUN Y H, YIN Y H. The effect of air change rate and temperature on phthalate concentration in house dust[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 639: 760-768. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.05.097 [58] LI Y H, LU J J, YIN X W, et al. Indoor phthalate concentrations in residences in Shihezi, China: Implications for preschool children’s exposure and risk assessment[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 2019, 26(19): 19785-19794. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-05335-3 [59] LIU K, KANG L Y, LI A, et al. Field investigation on phthalates in settled dust from five different surfaces in residential apartments[J]. Building and Environment, 2020, 177: 106856. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.106856 [60] DUAN J H, WANG L X, ZHUO S H, et al. Seasonal variation of airborne phthalates in classroom and dormitory, and its exposure assessment in college students[J]. Energy and Buildings, 2022, 265: 112078. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2022.112078 [61] LIM S. The associations between personal care products use and urinary concentrations of phthalates, parabens, and triclosan in various age groups: The Korean National Environmental Health Survey Cycle 3 2015-2017[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 742: 140640. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140640 [62] FICHEUX A S, WESOLEK N, CHEVILLOTTE G, et al. Consumption of cosmetic products by the French population. First part: Frequency data[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2015, 78: 159-169. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2015.01.016 [63] SAINI A, OKEME J O, MARK PARNIS J, et al. From air to clothing: Characterizing the accumulation of semi-volatile organic compounds to fabrics in indoor environments[J]. Indoor Air, 2017, 27(3): 631-641. doi: 10.1111/ina.12328 [64] 宋怡. 大同市区春夏季道路灰尘中重金属与多环芳烃污染研究[D]. 西安: 陕西师范大学, 2020. SONG Y. Study on pollution of heavy metals and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in road dust in Datong city in spring and summer[D]. Xi'an: Shaanxi Normal University, 2020 (in Chinese).

[65] 王钰. 哈尔滨市主城区道路灰尘重金属污染研究[D]. 哈尔滨: 哈尔滨师范大学, 2022. WANG Y. Study on heavy metal pollution of road dust in the main urban area of Harbin[D]. Harbin: Harbin Normal University, 2022 (in Chinese).

[66] 马晓丽, 何雨恒, 张辉等. 福州市道路灰尘中多环芳烃粒径分布、生物可利用度及其毒性当量[J]. 环境化学, 2024, 43(2): 515-523. MA X L, HE Y H, ZHANG H et al. Distribution, bioaccessability and toxicity equivalence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in different particle-size fractions of road dust in Fuzhou[J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2024, 43(2): 515-523(in Chinese).

[67] 刘正丹, 白文娟, 刘俊玲, 等. 武汉市居民住宅室内空气颗粒物中邻苯二甲酸酯污染状况[J]. 公共卫生与预防医学, 2020, 31(4): 36-40. LIU Z D, BAI W J, LIU J L, et al. Phthalate esters pollution in household indoor air particles in Wuhan[J]. Journal of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, 2020, 31(4): 36-40 (in Chinese).

[68] 赵祎. 上海市高校教室内邻苯二甲酸酯暴露研究[J]. 上海节能, 2019(9): 763-772. ZHAO Y. Study on phthalate exposure in university classrooms in Shanghai[J]. Shanghai Energy Conservation, 2019(9): 763-772 (in Chinese).

[69] OUYANG X Z, XIA M, SHEN X Y, et al. Pollution characteristics of 15 gas- and particle-phase phthalates in indoor and outdoor air in Hangzhou[J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2019, 86: 107-119. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2019.05.008 [70] 乔雅绮, 黄立辉. 住宅室内降尘中邻苯二甲酸酯的污染特征及传输途径[J]. 环境化学, 2020, 39(6): 1523-1529. doi: 10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2020020601 QIAO Y Q, HUANG L H. Characterization of phthalates in residential house dust and their transfer routes[J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2020, 39(6): 1523-1529 (in Chinese). doi: 10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2020020601

[71] ZHOU X J, LIAN J L, CHENG Y, et al. The gas/particle partitioning behavior of phthalate esters in indoor environment: Effects of temperature and humidity[J]. Environmental Research, 2021, 194: 110681. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110681 [72] 甄晓龙, 刘刚, 李久海, 等. 南京化工园区道路尘中邻苯二甲酸酯的时空变化和风险评估[J]. 环境化学, 2020, 39(2): 531-541. doi: 10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2019032502 ZHEN X L, LIU G, LI J H, et al. Spatial-temporal variation and risk assessment of phthalic acid esters in road dust of Nanjing chemical industry park[J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2020, 39(2): 531-541 (in Chinese). doi: 10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2019032502

[73] TANG Z W, CHAI M, WANG Y W, et al. Phthalates in preschool children’s clothing manufactured in seven Asian countries: Occurrence, profiles and potential health risks[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2020, 387: 121681. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121681 [74] GU Y, GAO M, ZHANG W W, et al. Exposure to phthalates DEHP and DINP May lead to oxidative damage and lipidomic disruptions in mouse kidney[J]. Chemosphere, 2021, 271: 129740. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.129740 [75] ZHANG Y J, WU L H, WANG F, et al. DNA oxidative damage in pregnant women upon exposure to conventional and alternative phthalates[J]. Environment International, 2021, 156: 106743. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106743 [76] van T ERVE T J, ROSEN E M, BARRETT E S, et al. Phthalates and phthalate alternatives have diverse associations with oxidative stress and inflammation in pregnant women[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2019, 53(6): 3258-3267. [77] PARRA-FORERO L Y, VELOZ-CONTRERAS A, VARGAS-MARÍN S, et al. Alterations in oocytes and early zygotes following oral exposure to di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate in young adult female mice[J]. Reproductive Toxicology, 2019, 90: 53-61. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2019.08.012 [78] LIN C Y, CHEN C W, LEE H L, et al. Global DNA methylation mediates the association between urine mono-2-ethylhexyl phthalate and serum apoptotic microparticles in a young Taiwanese population[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2022, 808: 152054. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152054 [79] GAO X Y, CUI L, MU Y M, et al. Cumulative health risk in children and adolescents exposed to bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP)[J]. Environmental Research, 2023, 237: 116865. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2023.116865 -

下载:

下载: