-

水是人类生存与社会发展的基础. 饮用水,作为直接供给人体饮用的水源,其质量与公众健康密切相关. 为保证饮用水安全,通常需要向水中添加消毒剂以杀死水中的病原菌. 常用消毒剂如氯气或氯胺等可能与水中的有机物或污染物发生反应并产生消毒副产物[1]. 卤代苯醌是近年来水体中发现的一类未受管控且具有潜在毒理学效应的新型DBPs[2 − 7]. 虽然其在各类水体中浓度约为ng·L−1级别[8],但相比于已受到美国环境保护署、欧洲联盟理事会及世界卫生组织管控的DBPs,HBQs表现出更高的细胞毒性和遗传毒性[9 − 12]. 有研究表明长期饮用氯化消毒后的饮用水可能增加患膀胱癌的风险[13]. 此外,定量结构毒性关系分析预测HBQs是潜在的膀胱癌致癌物质[14]. 因此,HBQs可能会对人类健康及生态环境的安全构成威胁. 本文重点关注HBQs的化学特征与形成机制、环境污染分布及毒性作用.

-

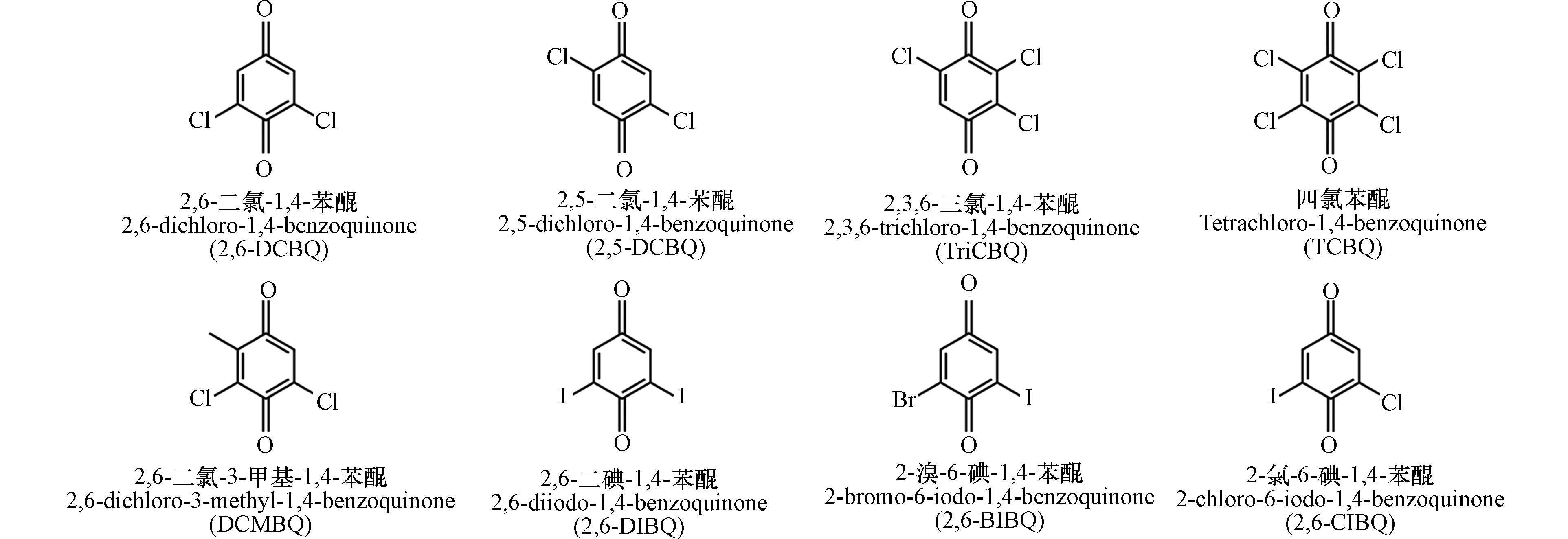

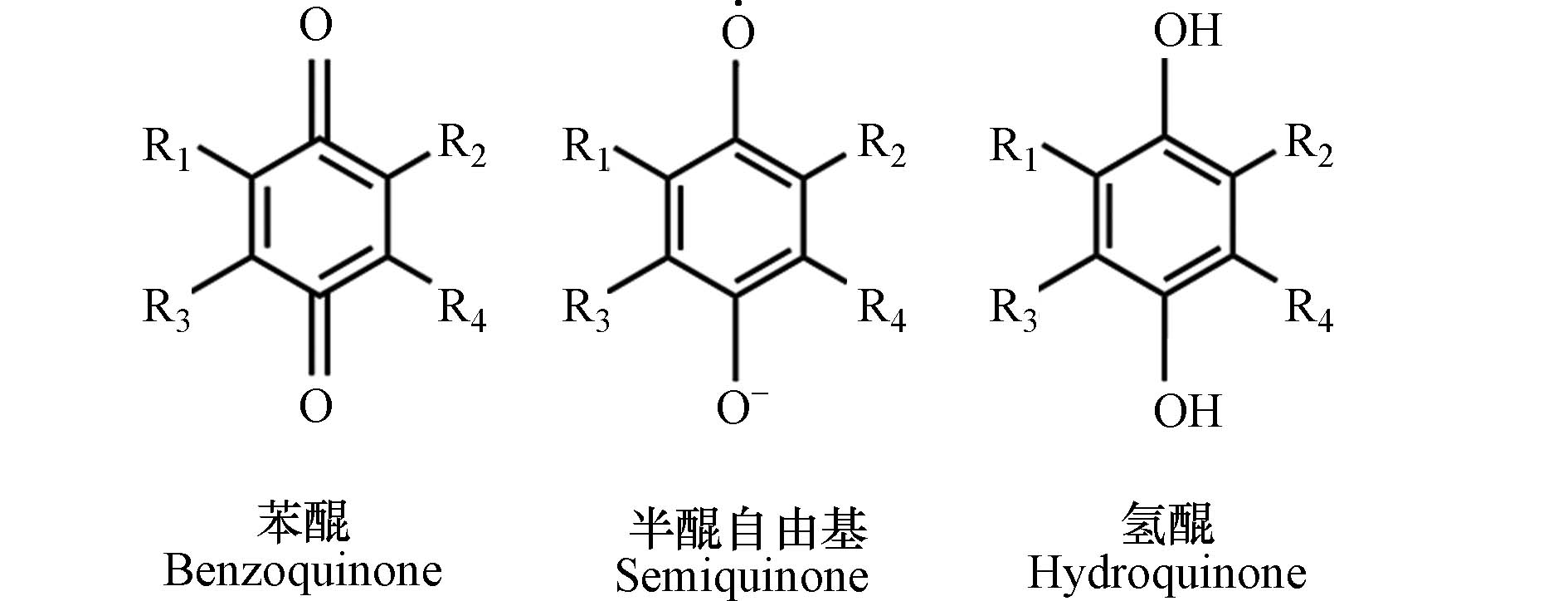

HBQs的结构基础是苯醌(benzoquinone, BQ),其环上带有卤素、烷基或羟基修饰(图1). 这类化合物含有高极性的羰基,与芳香醌类化合物相似. HBQs的化学性质与BQ密切相关,尤其在氧化还原和加成反应方面[15]. BQ得电子还原为半醌自由基和氢醌(hydroquinone, HQ)[16],也可与氧亲核试剂发生氧化反应生成醌环氧化物[17],在水溶液中形成多个与HBQs结构类似的氧化还原态.

HBQs并非自然界中存在的天然有机物,其形成需要水中特定的化合物与消毒剂发生反应. 这些化合物包括游离芳香族氨基酸[18]、苯醌类似物[19 − 20]、芳香型天然有机物[3]及藻类[21 − 22] 等. 几种常见的HBQs如图2所示.

-

HBQs广泛存在于氯消毒处理的水体中. 自2010年首次在加拿大饮用水中检出以来[4, 5],目前世界多地的饮用水中均检出了HBQs. 例如,2012年美国和加拿大[23]9个饮用水处理厂的16份水样本中检出了多种HBQs,包括2,6-DCBQ、2,6-DBBQ、TriCBQ和DCMBQ. 其中2,6-DCBQ的检出浓度为4.5—274.5 ng·L−1且检出率高达100%,DCMBQ和TriCBQ的检出率分别为37.5%和18.8%. 2015年日本的12座水厂水样[24]中也发现了2,6-DCBQ,检出率为87.5%,检出浓度为8.0—51.0 ng·L−1.

近年来,我国多地饮用水体中也检测出HBQs:2021年天津[25]水处理厂和相关配水网络中检出2,6-DCBQ,采样点2,6-DCBQ的浓度随着与饮用水处理厂距离的增加而逐渐降低;2020年南京和上海[9]不同地区的饮用水中首次检测出了3种新型碘化HBQs(2,6-CIBQ、2,6-BIBQ和2,6-DIBQ),碘化HBQs比常见的氯化HBQs(如2,6-DCBQ)具有更强的细胞毒性,因此含有碘化HBQs的饮用水可能对人体健康产生更大的威胁[26]. 此外,HBQs也在茶水中检出,且其检出浓度与茶叶的发酵程度呈现正相关性. 这可能与饮用水或茶叶的发酵工艺相关,茶叶发酵过程中的过氧化物酶和多酚氧化酶会与植物中无机氯与酚基发生反应可能会导致HBQs生成[27].

除饮用水外,HBQs也存在于经氯消毒处理的游泳池用水中. 经氯消毒的泳池水中2,6-DCBQ的浓度在19—299 ng·L−1之间,较未经消毒的自来水浓度(1—6 ng·L−1)提高了100倍[28]. 中国南宁[5]7个公共游泳池中的2,6-DCBQ检出率为100%,浓度范围为4.56—45.30 ng·L−1. 游泳池中的氯代苯醌浓度高于自来水,这与加拿大的研究结果一致. 与仅通过氯化消毒产生HBQs的饮用水不同,泳池水的化学暴露环境更为复杂. 例如,游泳者所用的化妆品(如防晒霜和乳液等[6])中可能含有HBQs的前体化合物,在水中和其他化合物发生反应形成HBQs.

-

HBQs在水体中广泛分布,虽浓度较低但具有较高的潜在毒性. 近年来,针对卤代苯醌及其健康风险的研究广泛展开,通过流行病学研究和实验室研究,评估不同水平的卤代苯醌暴露对生命体的影响. HBQs已被发现在细胞毒性、氧化应激毒性、遗传毒性、对水生生物的毒性等多方面表现出毒性效应.

-

细胞毒性是指物质或因素对细胞产生有害的作用,可能导致细胞损伤或死亡. 基于细胞的环境污染物体外毒性检测已成为评估化合物毒性的一种重要手段,该方法可快速鉴定和识别具有潜在健康风险的新型污染物. 通过测量化合物的半致死浓度(IC50)可以对化学物质的毒性进行评估. HBQs 已被发现具有细胞毒性,在以人膀胱癌上皮T24细胞为毒性测试对象的研究中,4种HBQs(2,6-DCBQ、2,6-DBBQ、DCMBQ和TCBQ)的IC50值在微摩尔水平(1.9—95.6 μmol·L−1),其中饮用水中最常见的2,6-DCBQ对T24的毒性最强,这提示HBQs可能对人体泌尿系统有潜在危害. 而已受到管控的DBPs(N-亚硝基二甲胺、N-亚硝基二苯胺、N-亚硝基吡咯烷等)[29]对T24细胞的IC50值在毫摩尔水平(4.7—15.0 mmol·L−1),说明HBQs对T24细胞的潜在毒性远高于DBPs. 为保障公众健康,应采取措施将饮用水中2,6-DCBQ等HBQs的浓度控制在安全范围内. 此外,四种HBQs(2,6-DCBQ、2,6-DBBQ、DCMBQ和TCBQ)暴露中国仓鼠卵巢细胞CHO[30]得到的IC50也在微摩尔水平(15.9—72.9 μmol·L−1),而已受到管控的DBPs(三卤甲烷、卤乙酸)对CHO细胞的IC50在毫摩尔水平(3.96—11.5 mmol·L−1)[29]. HBQs对CHO细胞的毒性比传统的DBPs高出1000倍,上述研究证明HBQs具有较高的细胞毒性并可能对人体健康造成更严重的影响.

-

活性氧自由基(reactive oxygen species,ROS)引起的氧化应激是醌毒性作用机制之一[31]. HBQs中的半醌和羟基自由基结构会导致ROS的产生,引发细胞内氧化应激,进而对细胞造成氧化应激损伤[32]. HBQs还可以消耗细胞内谷胱甘肽(glutathione,GSH),影响细胞抗氧化酶系统,加剧氧化应激反应,导致细胞蛋白质和DNA损伤[11, 33]. 在T24细胞中,HBQs以浓度依赖的方式产生ROS,并对DNA和蛋白造成氧化损伤,而抗氧化剂可显著降低HBQs对T24细胞的毒性作用,表明ROS在HBQs诱导的细胞毒性中发挥重要作用[30]. 同时,HBQs以浓度依赖性的方式引起细胞GSH消耗和细胞谷胱甘肽S-转移酶活性的增加,质谱分析证实在水溶液和HepG2细胞中HBQs与 GSH可直接反应[32, 34],形成多种谷胱甘肽基偶联物(HBQ-SG),因此GSH的减少可能与其氧化或与HBQs结合有关[35]. 此外,HBQs可以显著改变尿路上皮细胞(SV-HUC-1)氧化应激相关信号通路的信号转导,从而影响细胞的功能和病理过程[36]. HBQs诱导的氧化应激也体现于活体水平. 例如,HBQs暴露会导致斑马鱼幼鱼体内ROS增加,超氧化物歧化酶活性降低,GSH含量减少,以及脂质过氧化水平和脂肪酸代谢异常. 而抗氧化剂可显著减轻HBQs诱导产生的影响,这些结果进一步证实了氧化应激介导HBQs毒性的结论[36-37].

-

遗传毒性是指化学物质或其他外部因素对生物体细胞的遗传物质造成损害或突变的能力. 这些改变可能直接或间接影响遗传信息,从而影响个体健康及后代的遗传稳定性. 已有证据表明HBQs能够诱导突变,具有遗传毒性作用.

-

HBQs能够直接或间接作用于细胞DNA,导致细胞遗传信息的改变. HBQs是反应性亲电物质,可诱导显著的遗传毒性:与DNA形成加合物[38],阻断DNA聚合酶活性,诱导缺失突变、特定位点突变或序列特异性突变等[39]. 毒理基因组学分析显示,HBQs干扰人膀胱上皮细胞SV-HUC-1的DNA修复途径,主要影响碱基切除修复、核苷酸切除修复和同源重组修复[40]. 在经过TCBQ处理的HeLaS3细胞中检出DNA加合物二氯苯醌核苷(Cl2BQ-dG)[41 − 42]. 在SupF报告基因突变试验中,HBQs诱导GC碱基对上的单碱基替换,主要是GC→TA翻转和GC→AT突变[43]. 此外,如果HBQs与关键基因形成DNA加合物则可能发生致癌突变.

-

HBQs诱导的DNA氧化损伤可能导致DNA结构和功能的异常,增加细胞突变或发生癌症等风险. DNA氧化损伤主要表现为细胞DNA链断裂、8-羟基脱氧鸟苷(8-hydroxy-2deoxyguanosine,8-OHdG)和脱嘌呤/脱嘧啶位点(apurinic/apyrimidinic sites,AP sites)的显著增加等. HBQs诱导T24细胞的基因组DNA中产生8-OHdG,且DCMBQ诱导生成的8-OHdG水平高于2,6-DCBQ、2,6-DBBQ和TCBQ[30];HBQs也会引起哺乳动物CHO卵巢细胞中p53蛋白和8-OHdG的表达升高[44],p53作为肿瘤抑制蛋白,在协调细胞对基因毒性应激的反应中起着至关重要的作用[45]. 体内实验证明HBQs会导致斑马鱼幼鱼体内8-OHdG水平升高、DNA片段化并诱导凋亡相关基因表达变化[37]. 在HBQs处理的HepG2细胞中检出了γ-H2AX,表明HBQs诱发DNA双链断裂,而ROS清除剂的预处理显著抑制了这种情况,说明HBQs可能通过ROS介导DNA氧化损伤导致HepG2细胞的遗传毒性[46]. 在TCHQ处理的HeLaS3细胞中观察到AP位点的形成[47],说明HBQs可能干扰正常的DNA修复机制,导致遗传信息改变进而引发疾病. 因此,减少甚至避免HBQs的暴露是降低DNA氧化损伤风险的重要措施.

-

外部因素(如辐射、化学物质和病毒等)或内部因素(如氧化应激、DNA复制错误等)可能导致生物染色体结构或功能上的损害. 这些损伤可能影响细胞的正常功能、代谢和生长,最终导致细胞死亡、突变,甚至引发癌症[48]. 微核检测(micronucleus assay)通过测量染色体丢失和染色体断裂来评估染色体损伤程度,可用于评估个体暴露于环境致癌物质和诱变剂的遗传风险[49]. HBQs暴露显著增加HepG2细胞中的微核频率,表明HBQs可能导致染色体断裂[46]. HBQs可诱导人类细胞系膀胱癌5637细胞、结肠癌Caco-2细胞和胃癌MGC-803细胞染色体损伤,导致微核显著增加,其中DCMBQ对所有测试细胞系的细胞毒性和遗传毒性最高,TCBQ对所有测试细胞系的毒性最低[50].

-

DNA 5-甲基胞嘧啶(5-Methylcytosine,5mC)甲基化是哺乳动物中一种主要的表观遗传学标记[51]. TET双加氧酶(Ten-Eleven-Translocation enzymes)能催化5mC氧化生成5-羟甲基胞嘧啶(5-hydroxymethylcytosine, 5hmC),介导DNA的主动去甲基化[52],这一过程对于调控DNA甲基化水平至关重要. HBQs的暴露会导致细胞内游离亚铁离子含量的升高,而亚铁离子是TET酶的辅助因子之一 [53],增加的亚铁离子可以提高TET酶的催化活性,从而促进5hmC的形成. 5mC向5hmC的转换不仅与表观遗传的重编程紧密相关,而且对于DNA的动态去甲基化和组织特异性基因表达的调控也具有重要意义[54 − 55]. 异常5hmC水平可能干扰细胞内正常的DNA甲基化模式,HBQs诱导多基因的去甲基化[56],这些基因涉及蛋白质代谢、细胞凋亡、细胞定位与运输以及RNA的加工处理等多个关键生物进程[57, 58]. 此外,癌细胞通常呈现出全基因组的低甲基化[59],若DNA去甲基化介导癌基因激活,还可能促进肿瘤发生[60]. 因此,HBQs可能改变表观遗传修饰水平而具有潜在的致癌性.

-

HBQs广泛存在于水环境中,因此评估HBQs对水生生物的毒性至关重要. 斑马鱼作为研究毒性效应的首选水生生物模型,被广泛应用于研究HBQs对水生动物的毒性,这包括斑马鱼在发育过程中受到的损害、心脏和血管系统的不良影响、神经系统的损伤以及因氧化应激和代谢异常导致的毒性作用等.

水生生物的正常生长发育离不开健康的水环境,但是水体中HBQs会对斑马鱼造成发育毒性. 2,5-DCBQ影响斑马鱼早期胚胎的正常发育,造成外胚层发育的延迟甚至死亡[61];HBQs的处理会导致斑马鱼幼鱼出现明显的发育畸形,如体长缩短、鱼鳔充气失败、心脏畸形和脊柱弯曲等[37],其中鱼鳔充气失败可能会导致运动和摄入受限,最终导致死亡率增加[62]. 此外,2,6-DCBQ暴露可能导致雌性斑马鱼青春期延迟、卵巢生长迟缓和生育能力低下,并可能通过破坏17-β雌二醇水平诱导雌性斑马鱼生殖损伤[63]. 且暴露于饮用水消毒副产物或可增加女性卵巢储备功能下降的风险,降低女性生育能力[64].

流行病学研究表明,饮用水中消毒副产物含量的增加与心脏先天性缺陷的风险相关. 研究发现,孕妇早期接触高水平的DBPs增加新生儿出现先天性心脏缺陷的风险[65]. 斑马鱼发育过程的透明以及与人类相似的心血管系统使其成为研究HBQs心血管毒性的理想模型. 2,6-DCBQ暴露导致斑马鱼胚胎心房-心室变形、心包水肿、腹部及主干血管变形和血流量减少. 这些心脏与血管的畸形可能直接影响心脏泵血功能及正常的输血输氧,导致心跳异常和循环衰竭甚至死亡. 此外,心脏特异性标记基因myl7的表达受到抑制,该基因对心肌细胞的分化和运动至关重要,也证明了HBQs对心脏发育的潜在风险 [37, 66].

HBQs影响人神经干细胞正常的细胞周期,进而阻碍细胞增殖与分化[67],表明HBQs具有潜在神经毒性[68]. HBQs对斑马鱼神经毒性的影响主要表现为运动神经毒性和视觉神经毒性[69, 70]. 经HBQs处理过的幼鱼(120 hpf)运动行为能力显著低于正常组,并且神经递质含量降低、神经调节相关基因下调,表明HBQs具有运动神经毒性[37];HBQs暴露导致视网膜特定功能相关的多晶体蛋白和角蛋白水平增加,提示HBQs具有视觉神经毒性效应[71].

HBQs还引起斑马鱼代谢水平的变化. 经2,5-DCBQ处理的斑马鱼胚胎表现出代谢异常,且这种异常与暴露浓度呈现正相关性. 生物信息分析显示其代谢通路(嘌呤代谢、氨酰-tRNA生物合成等)发生显著改变[61]. 2,6-DCBQ显著改变斑马鱼胚胎中的脂质过氧化水平和脂肪酸代谢[37]. HBQs可能对斑马鱼的代谢功能产生明显的毒性影响,进而影响其正常的生命活动.

-

饮用水消毒副产物HBQs存在于氯消毒的饮用水和游泳池水体中,是近年来备受关注的一类新型污染物. 通过了解HBQs的结构特征和形成机制,可以更好地评估其潜在毒性和环境行为,为相关监管和控制提供科学依据. 研究HBQs的毒性效应及机理将有助于评估其对人体和环境的风险水平,从而制定相关的安全措施和监管政策,以降低该类化合物对人体和环境的潜在风险. 为了保障公众健康和环境安全,需要加强对HBQs的毒理学研究,包括生物累积和生物放大效应、环境污染物相互作用机理和影响、人类健康风险评估等. 此外,尽管自来水中DBPs(二氯乙酸和三氯乙酸)已被证明具有内分泌干扰物效应[72],但HBQs是否也具有类似效应,影响人体内分泌系统和生殖、发育等过程,目前的研究仍然不足. 因此,HBQs的毒理研究仍然需要进行深入、全面的探索和研究,以确定其对人体健康的潜在风险,这项工作将是未来的长期任务.

卤代苯醌类消毒副产物的毒理学研究进展

Research progress on toxicology of haloquinoid disinfection byproducts

-

摘要: 卤代苯醌(halobenzoquinones, HBQs)是近年来在水体中发现的一类具有潜在毒理学效应且未受管控的新型消毒副产物(disinfection by-products, DBPs). 本文综述了HBQs的化学特征与生成机制、环境中的分布情况,并对其引起的细胞毒性、氧化应激毒性、遗传毒性、生物毒性进行了概述. 这些内容旨在为深入探讨HBQs的毒理学机制和全面评估其暴露所可能导致的健康风险及癌症风险提供科学依据.Abstract: Halobenzoquinones (HBQs) are newly identified, unregulated disinfection by-products (DBPs) with potential toxicity, recently found in various water bodies. This article reviews the chemical properties, and formation mechanisms of HBQs, as well as their environmental distribution. It provides an extensive overview of the toxicological impacts of HBQs exposure, including cytoxicity, oxidative stress toxicity, genetic toxicity, and other biological effects. The goal is to offer a scientific basis for further investigation into the toxicological mechanisms of HBQs and to enhance understanding of the potential health risks associated with HBQs exposure.

-

-

[1] ZHAO H, HUANG C-H, ZHONG C, et al. Enhanced formation of trihalomethane disinfection byproducts from halobenzoquinones under combined UV/chlorine conditions[J]. Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering, 2022, 16: 1-11. [2] RICHARDSON S D, TERNES T A. Water analysis: Emerging contaminants and current issues[J]. Analytical Chemistry, 2022, 94(1): 382-416. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.1c04640 [3] LOU J, LU H, WANG W, et al. Molecular composition of halobenzoquinone precursors in natural organic matter in source water[J]. Water Research, 2022, 209: 117901. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117901 [4] ZHAO Y L, QIN F, BOYD J M, et al. Characterization and determination of chloro- and bromo-benzoquinones as new chlorination disinfection byproducts in drinking water[J]. Analytical Chemistry, 2010, 82(11): 4599-4605. doi: 10.1021/ac100708u [5] QIN F, ZHAO Y Y, ZHAO Y L, et al. A toxic disinfection by-product, 2, 6-dichloro-1, 4-benzoquinone, identified in drinking water[J]. Angewandte Chemie (International Ed. in English), 2010, 49(4): 790-792. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904934 [6] WANG W, QIAN Y C, BOYD J M, et al. Halobenzoquinones in swimming pool waters and their formation from personal care products[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2013, 47(7): 3275-3282. [7] JEONG C H, WAGNER E D, SIEBERT V R, et al. Occurrence and toxicity of disinfection byproducts in European drinking waters in relation with the HIWATE epidemiology study[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2012, 46(21): 12120-12128. [8] HUANG R F, WANG W, QIAN Y C, et al. Ultra pressure liquid chromatography-negative electrospray ionization mass spectrometry determination of twelve halobenzoquinones at ng/L levels in drinking water[J]. Analytical Chemistry, 2013, 85(9): 4520-4529. doi: 10.1021/ac400160r [9] HU S Y, GONG T T, ZHU H T, et al. Formation and decomposition of new iodinated halobenzoquinones during chloramination in drinking water[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2020, 54(8): 5237-5248. [10] HU S Y, CHEN X, ZHANG B B, et al. Occurrence and transformation of newly discovered 2-bromo-6-chloro-1, 4-benzoquinone in chlorinated drinking water[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2022, 436: 129189. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.129189 [11] HU S, LI X, HE F, et al. Cytotoxicity of emerging halophenylacetamide disinfection byproducts in drinking water: Mechanism and prediction[J]. Water Research, 2024, 256: 121562. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2024.121562 [12] LI J H, MOE B, VEMULA S, et al. Emerging disinfection byproducts, halobenzoquinones: Effects of isomeric structure and halogen substitution on cytotoxicity, formation of reactive oxygen species, and genotoxicity[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2016, 50(13): 6744-6752. [13] BROOKS T, ROBERTSON W. Safe drinking water, lessons from recent outbreaks in affluent nations[J]. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 2005, 96(1): 23. doi: 10.1007/BF03404008 [14] ZHAO Y L, ANICHINA J, LU X F, et al. Occurrence and formation of chloro- and bromo-benzoquinones during drinking water disinfection[J]. Water Research, 2012, 46(14): 4351-4360. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2012.05.032 [15] NAMAZIAN M, COOTE M L. Accurate calculation of absolute one-electron redox potentials of some para-quinone derivatives in acetonitrile[J]. The Journal of Physical Chemistry. A, 2007, 111(30): 7227-7232. doi: 10.1021/jp0725883 [16] WANG W, MOE B, LI J H, et al. Analytical characterization, occurrence, transformation, and removal of the emerging disinfection byproducts halobenzoquinones in water[J]. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2016, 85: 97-110. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2016.03.004 [17] EL-NAJJAR N, GALI-MUHTASIB H, KETOLA R A, et al. The chemical and biological activities of quinones: overview and implications in analytical detection[J]. Phytochemistry Reviews, 2011, 10(3): 353-370. doi: 10.1007/s11101-011-9209-1 [18] ZHAO J X, HU S Y, ZHU L Z, et al. Formation of chlorinated halobenzoquinones during chlorination of free aromatic amino acids[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2022, 825: 153904. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153904 [19] FAN Y, SUN G, KAW H Y, et al. Analytical characterization of nucleotides and their concentration variation in drinking water treatment process[J]. Science of The Total Environment, 2022, 817: 152510. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152510 [20] GE F, XIAO Y, YANG Y X, et al. Formation of water disinfection byproduct 2, 6-dichloro-1, 4-benzoquinone from chlorination of green algae[J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences (China), 2018, 63: 1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2017.10.001 [21] HRUDEY S E. Chlorination disinfection by-products, public health risk tradeoffs and me[J]. Water Research, 2009, 43(8): 2057-2092. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2009.02.011 [22] VILLANUEVA C M, CANTOR K P, GRIMALT J O, et al. Bladder cancer and exposure to water disinfection by-products through ingestion, bathing, showering, and swimming in pools[J]. American Journal of Epidemiology, 2007, 165(2): 148-156. [23] Diemert S, Wang W, Andrews R C, et al. Removal of halo-benzoquinone (emerging disinfection by-product) precursor material from three surface waters using coagulation[J]. Water Research, 2013, 47(5): 1773-1782. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2012.12.035 [24] NAKAI T, KOSAKA K, ASAMI M, et al. Analysis and occurrence of 2, 6-dichloro-1, 4-benzoquinone in drinking water by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry[J]. Journal of Japan Society on Water Environment, 2015, 38(3): 67-73. doi: 10.2965/jswe.38.67 [25] LI Y N, ZHANG L F, YANG L M, et al. Hydrolysis characteristics and risk assessment of a widely detected emerging drinking water disinfection-by-product-2, 6-dichloro-1, 4-benzoquinone-in the water environment of Tianjin (China)[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 765: 144394. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144394 [26] WU Y, WEI W, LUO J, et al. Comparative toxicity analyses from different endpoints: are new cyclic disinfection byproducts (DBPs) more toxic than common aliphatic DBPs?[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2021, 56(1): 194-207. [27] LOU J X, WANG W, ZHU L Z. Occurrence, formation, and oxidative stress of emerging disinfection byproducts, halobenzoquinones, in tea[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2019, 53(20): 11860-11868. [28] LaKIND J S, RICHARDSON S D, BLOUNT B C. The good, the bad, and the volatile: Can we have both healthy pools and healthy people?[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2010, 44(9): 3205-3210. [29] BOYD J M, HUANG L, XIE L, et al. A cell-microelectronic sensing technique for profiling cytotoxicity of chemicals[J]. Analytica Chimica Acta, 2008, 615(1): 80-87. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2008.03.047 [30] DU H Y, LI J H, MOE B, et al. Cytotoxicity and oxidative damage induced by halobenzoquinones to T24 bladder cancer cells[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2013, 47(6): 2823-2830. [31] O’BRIEN P J. Molecular mechanisms of quinone cytotoxicity[J]. Chemico-Biological Interactions, 1991, 80(1): 1-41. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(91)90029-7 [32] SONG Y, WAGNER B A, WITMER J R, et al. Nonenzymatic displacement of chlorine and formation of free radicals upon the reaction of glutathione with PCB quinones[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2009, 106(24): 9725-9730. [33] ZHOU M, LI J, DU M, et al. Methoxylated Modification of Glutathione-Mediated Metabolism of Halobenzoquinones In Vivo and In Vitro[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2023, 57(9): 3581-3589. [34] WANG W, QIAN Y C, LI J H, et al. Characterization of mechanisms of glutathione conjugation with halobenzoquinones in solution and HepG2 cells[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52(5): 2898-2908. [35] LI J H, WANG W, ZHANG H Q, et al. Glutathione-mediated detoxification of halobenzoquinone drinking water disinfection byproducts in T24 cells[J]. Toxicological Sciences: an Official Journal of the Society of Toxicology, 2014, 141(2): 335-343. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu088 [36] LI J H, MOE B, LIU Y M, et al. Halobenzoquinone-induced alteration of gene expression associated with oxidative stress signaling pathways[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52(11): 6576-6584. [37] WANG C, YANG X, ZHENG Q, et al. Halobenzoquinone-induced developmental toxicity, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in zebrafish embryos[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52(18): 10590-10598. [38] WAIDYANATHA S, LIN P H, RAPPAPORT S M. Characterization of chlorinated adducts of hemoglobin and albumin following administration of pentachlorophenol to rats[J]. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 1996, 9(3): 647-653. doi: 10.1021/tx950172n [39] WANG J, YU S Y, JIAO S H, et al. Characterization of TCHQ-induced genotoxicity and mutagenesis using the pSP189 shuttle vector in mammalian cells[J]. Mutation Research, 2012, 729(1/2): 16-23. [40] ZHANG X, LIU L, WANG J, et al. The alternation of halobenzoquinone disinfection byproduct on toxicogenomics of DNA damage and repair in uroepithelial cells[J]. Environment International, 2024, 183: 108407. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2023.108407 [41] NGUYEN T N T, BERTAGNOLLI A D, VILLALTA P W, et al. Characterization of a deoxyguanosine adduct of tetrachlorobenzoquinone: Dichlorobenzoquinone-1, N2-etheno-2'-deoxyguanosine[J]. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 2005, 18(11): 1770-1776. doi: 10.1021/tx050204z [42] XIONG Y, KAW H Y, ZHU L, et al. Genotoxicity of quinone: an insight on DNA adducts and its LC-MS-based detection[J]. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 2022, 52(23): 4217-40. doi: 10.1080/10643389.2021.2001276 [43] GASKELL M, McLUCKIE K I E, FARMER P B. Comparison of the repair of DNA damage induced by the benzene metabolites hydroquinone and p-benzoquinone: A role for hydroquinone in benzene genotoxicity[J]. Carcinogenesis, 2005, 26(3): 673-680. [44] WAGNER E D, PLEWA M J. CHO cell cytotoxicity and genotoxicity analyses of disinfection by-products: An updated review[J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences (China), 2017, 58: 64-76. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2017.04.021 [45] BROOKS C L, GU W. p53 ubiquitination: Mdm2 and beyond[J]. Molecular Cell, 2006, 21(3): 307-315. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.020 [46] DONG H, SU C Y, XIA X M, et al. Polychlorinated biphenyl quinone-induced genotoxicity, oxidative DNA damage and γ-H2AX formation in HepG2 cells[J]. Chemico-Biological Interactions, 2014, 212: 47-55. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2014.01.016 [47] NAKAMURA J, LA D K, SWENBERG J A. 5'-nicked apurinic/apyrimidinic sites are resistant to beta-elimination by beta-polymerase and are persistent in human cultured cells after oxidative stress[J]. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2000, 275(8): 5323-5328. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5323 [48] FENECH M. The in vitro micronucleus technique[J]. Mutation Research, 2000, 455(1-2): 81-95. doi: 10.1016/S0027-5107(00)00065-8 [49] RANGEL-LÓPEZ A, PANIAGUA-MEDINA M E, URBÁN-REYES M, et al. Genetic damage in patients with chronic kidney disease, peritoneal dialysis and haemodialysis: A comparative study[J]. Mutagenesis, 2013, 28(2): 219-225. doi: 10.1093/mutage/ges075 [50] LI J B, ZHANG H F, HAN Y N, et al. Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity assays of halobenzoquinones disinfection byproducts using different human cell lines[J]. Environmental and Molecular Mutagenesis, 2020, 61(5): 526-533. doi: 10.1002/em.22369 [51] HOTCHKISS R D. The quantitative separation of purines, pyrimidines, and nucleosides by paper chromatography[J]. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1948, 175(1): 315-332. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)57261-6 [52] XU G L, BOCHTLER M. Reversal of nucleobase methylation by dioxygenases[J]. Nature Chemical Biology, 2020, 16: 1160-1169. doi: 10.1038/s41589-020-00675-5 [53] TAHILIANI M, KOH K P, SHEN Y H, et al. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1[J]. Science, 2009, 324(5929): 930-935. doi: 10.1126/science.1170116 [54] BRANCO M R, FICZ G, REIK W. Uncovering the role of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the epigenome[J]. Nature Reviews Genetics, 2012, 13: 7-13. [55] WU H, ZHANG Y. Mechanisms and functions of Tet protein-mediated 5-methylcytosine oxidation[J]. Genes & Development, 2011, 25(23): 2436-2452. [56] FANG T, TANG C, YIN J, et al. Magnetic multi-enzyme cascade combined with liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry for fast DNA digestion and quantitative analysis of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in genome of human bladder cancer T24 cells induced by tetrachlorobenzoquinone[J]. Journal of Chromatography A, 2022, 1676: 463279. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2022.463279 [57] LI C P, WANG F B, WANG H L. Tetrachloro-1, 4-benzoquinone induces apoptosis of mouse embryonic stem cells[J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences (China), 2017, 51: 5-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2016.04.026 [58] ZHAO B L, YANG Y, WANG X L, et al. Redox-active quinones induces genome-wide DNA methylation changes by an iron-mediated and Tet-dependent mechanism[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2014, 42(3): 1593-1605. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1090 [59] FEINBERG A P, VOGELSTEIN B. Hypomethylation distinguishes genes of some human cancers from their normal counterparts[J]. Nature, 1983, 301: 89-92. doi: 10.1038/301089a0 [60] ZHOU H, CHEN W D, QIN X, et al. MMTV promoter hypomethylation is linked to spontaneous and MNU associated c-neu expression and mammary carcinogenesis in MMTV c-neu transgenic mice[J]. Oncogene, 2001, 20(42): 6009-6017. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204830 [61] CHEN Y Y, WANG J M, YU Z Q, et al. Transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses revealed epiboly delayed mechanisms of 2, 5-dichloro-1, 4-benuinone on zebrafish embryos[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2023, 30(27): 71360-71370. doi: 10.1007/s11356-023-27145-4 [62] LI J, LIANG Y, ZHANG X, et al. Impaired gas bladder inflation in zebrafish exposed to a novel heterocyclic brominated flame retardant tris(2, 3-dibromopropyl) isocyanurate[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2011, 45(22): 9750-9757. [63] SONG W Y, WU K, WU X L, et al. The antiestrogen-like activity and reproductive toxicity of 2, 6-DCBQ on female zebrafish upon sub-chronic exposure[J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences (China), 2022, 117: 10-20. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2021.11.012 [64] DENG Y-L, LUO Q, LIU C, et al. Urinary biomarkers of exposure to drinking water disinfection byproducts and ovarian reserve: a cross-sectional study in China[J]. Journal of hazardous materials, 2022, 421: 126683. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126683 [65] WRIGHT J M, EVANS A, KAUFMAN J A, et al. Disinfection by-product exposures and the risk of specific cardiac birth defects[J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2017, 125(2): 269-277. doi: 10.1289/EHP103 [66] YANG X, WANG C, ZHENG Q, et al. Emerging disinfection byproduct 2, 6-dichlorobenzoquinone-induced cardiovascular developmental toxicity of embryonic zebrafish and larvae: Imaging and transcriptome analysis[J]. ACS Omega, 2022, 7(49): 45642-45653. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.2c06296 [67] FU K Z, LI J H, VEMULA S, et al. Effects of halobenzoquinone and haloacetic acid water disinfection byproducts on human neural stem cells[J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences (China), 2017, 58: 239-249. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2017.02.006 [68] LIU Z, LV X, YANG B, et al. Tetrachlorobenzoquinone exposure triggers ferroptosis contributing to its neurotoxicity[J]. Chemosphere, 2021, 264: 128413. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128413 [69] KINKHABWALA A, RILEY M, KOYAMA M, et al. A structural and functional ground plan for neurons in the hindbrain of zebrafish[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2011, 108(3): 1164-1169. [70] PORTUGUES R, ENGERT F. The neural basis of visual behaviors in the larval zebrafish[J]. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 2009, 19(6): 644-647. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.10.007 [71] GRAW J. From eyeless to neurological diseases[J]. Experimental Eye Research, 2017, 156: 5-9. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2015.11.006 [72] CHEN W, WANG X, WAN S, et al. Dichloroacetic acid and trichloroacetic acid as disinfection by-products in drinking water are endocrine-disrupting chemicals[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2024, 466: 133035. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.133035 -

下载:

下载: